With the horror genre in an undeniable peak with hits both commercial (“Halloween”) and critical (“Hereditary”), and every fan of spooky cinema’s favorite holiday on the horizon, it's time for a great movie marathon. Of course, we would never discourage you from including widely-acknowledged classics like most of the films of George A. Romero, John Carpenter, and David Cronenberg, but what if you want to distinguish your marathon from your neighbor’s? What if you want to think outside the bloody box? We asked our staff to contribute an “underrated” horror film with no further definition of that word—whatever it meant to them. The results are a fascinating array of films from different eras and backgrounds. Pick out a few or get really ambitious and watch them all. Most of these are available on streaming services like iTunes, Amazon Prime, or Vudu.

Horror maestro Stuart Gordon re-teamed with "Re-Animator" co-stars Barbara Crampton and Jeffrey Combs (as well as "Re-Animator" co-writer Dennis Paoli and producer Brian Yuzna) for the 1986 gross-out gem "From Beyond," another loose and sticky homage to genre titan and noted racist H.P. Lovecraft's cosmic horrors. Here, Crampton plays Dr. McMichaels, a timid but ambitious psychiatrist who—with the help of traumatized physician Crawford Tillinghast (an endearingly hammy Combs) and wary Detective Bubba Brownlee (character actor god Ken Foree)—conducts a body-melting, mind-splitting experiment that stimulates the human brain's pineal gland. The film's cockeyed humor—"Like a gingerbread man!"—unabashed sexual kinks, and nightmarishly surreal creature effects (designed by John Carl Buechler and Mark Shostrom) suggest that Gordon and his collaborators really committed to delivering much more where "Re-Animator" came from, both in form and concept ("The machine is operating itself!"). This one's freak flag waves proudly and then some. (Simon Abrams)

Sam Raimi returned to his horror roots in 2009 following the immense commercial success of his “Spider-Man” films with the devilishly fun “Drag Me to Hell.” Horror lovers are familiar with Raimi from his series of “Evil Dead” films, and “Drag Me to Hell” featured many of the hallmarks that made him such a beloved directord—kinetic filmmaking, grotesque horror, and a twisted sense of humor that mixes the macabre with the Three Stooges. It also stands out as one of the first post-Great Recession horror films, as young bank worker Christine Brown (Alison Lohman) finds herself the subject of a gypsy woman’s curse when she denies the approval of a loan extension knowing full well that the choice will lead to foreclosure. On top of all the sick, twisted moments of body horror and haunting by demons from beyond, “Drag Me to Hell” is a frightening reminder that we’re all just one fateful choice away from losing grip on our lives and being dragged down to the pits of Hell. (Sean Mulvihill)

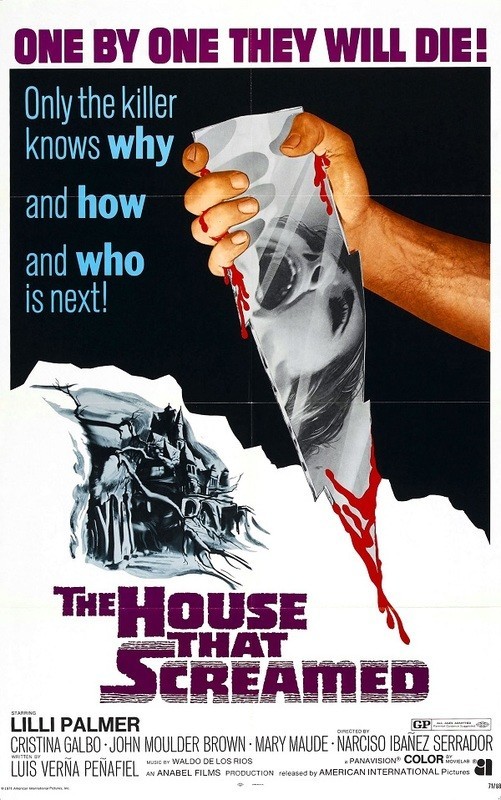

“The House That Screamed”

In “The House That Screamed,” young female students keep disappearing from an isolated boarding school in the South of France. A domineering headmistress claims they are running away, but the truth is far more sinister. Set in a large, brown Gothic house, every aspect of the girl's lives are controlled and this setting of repression leads to acts of rebellion and retaliatory punishments. In a classic tale of isolated women driven mad by desire, female sexuality grows monstrous, out of control and boils over into violence as the mystery deepens and expands. An underseen masterpiece of slow-burn euro-horror, “The House That Screamed” examines the cultish beliefs surrounding women’s shame and secrecy from director Narciso Ibáñez Serrador, best known for the horror cult-favorite “Who Can Kill a Child?” (Justine Smith)

“Parents”

Bob Balaban’s wonderfully weird and creepy “Parents” (or “Daddy Is A Cannibal” if you’re watching it in Germany) succeeds in being both fun to watch in the moment and hard to shake off after it ends. The tale of a boy (Bryan Madorsky) in the Eisenhower-era suburbs who learns his parents have a taste for human remains has a wicked sense of humor, a general sense of unease and David Lynchian flourishes of surrealism. It’s a wonder it all holds together with all these different tones coexisting in the same landscape. Imagine other more serious-minded movies about cannibals—“We Are What We Are” or “Raw”—put to the same soundtrack as “Ren & Stimpy.” Esquival music will never sound the same way again. At the center of it are two terrific performances from Mary Beth Hurt and Randy Quaid as the parents who cannot figure out why their kid always looks so freaked out all the time. (Collin Souter)

“The People Under the Stairs”

If Jordan Peele’s social satire “Get Out” is your preferred flavor of horror, Wes Craven’s horror-comedy "The People Under the Stairs" addressed many of the former’s anxieties as the Reagan years came to a close. Mommy (Wendy Robie) and Daddy (Everett McGill) run their evil household in a hellish vision of white conservatism, where god’s love has abandoned the suburbs and slum landlords have darker secrets than financial exploitation. Craven stuffs the house with plenty of practical effects and a tone that adds a silly bit of splatter to the Lynchian uncanniness of its "Twin Peaks" leads. The young “Fool” (Brandon Adams) has to cut through their haunted house and endless cruelties, which makes for a film that alternates between realistically jarring and bitingly funny. An anti-capitalist explosion with plenty of cannibals, traps, and creepiness, “The People Under the Stairs” is one of Craven’s best. (Jacob Oller)

“Cube”

Impress your friends at a Halloween viewing party with a ‘90s-tastic movie that has no discernible villain, takes place in an unspecified galaxy, and builds its nervous thrills out of solving elaborate math equations. And yet, Vincenzo Natali’s 1997 directorial debut “Cube” is an eerie sci-fi/horror delight, offering paranoia and select gore as a random group of people try to survive the deadly jungle gym in which they’ve been placed. Pre-dating the numbing torture of “Saw” and the torture porn craze, “Cube” gets its thrills out of its unpredictable plotting, with some rooms (spikes! wire! fire!) proving to have deadlier surprises than others. The existential dread of there possibly not being an exit to the Cube is just the beginning. A cherry on top: All three movies are now streaming on Netflix, including the larger-scale 2002 sequel “Cube 2: Hypercube” and the 2004 prequel, “Cube Zero.” (Nick Allen)

“The worst wolves are hairy on the inside.” So says a grandmother to her granddaughter, giving a cryptic warning in Neil Jordan’s “The Company of Wolves.” Adapted from several stories in Angela Carter’s marvelous The Bloody Chamber, “The Company of Wolves” is blood soaked and beautiful. The film turns stories like Little Red Riding Hood inside out to reveal them as tales of female sexual maturity, and the attendant fear of that they always were. Pointing the way to the feminist werewolf cult favorite “Ginger Snaps,” “The Company of Wolves” is beguiling, and trembles with ghostly forests and menstrual reds. There’s been a vogue for darker, actioned-up fairy tale retellings in recent years but it’s “The Company of Wolves” very willingness to sit still for a moment and create the feeling of listening to a dark tale by a crackling fire that has given it its lasting power. (Jessica Ritchey)

“The Blackcoat’s Daughter”

Directed by Oz Perkins, “The Blackcoat’s Daughter”—a supernatural psychological horror—requires an inquisitive eye and 93 minutes of patience to receive the maximum payoff. On a visceral level, Emma Roberts and Lucy Boynton’s performances make the experience worthwhile, but it’s “Mad Men”’s Kiernan Shipka who dominates the narrative with her off-kilter demeanor and wild-eyed transformation into a boarding school outcast gone mad. Perkins trusts the audience enough to focus and connect the dots, leaving the most telling information under the surface. As a whole, “The Blackcoat’s Daughter” shows restraint when one might expect excessive horror. Perkins maintains a specific mood and allows his female leads to build upon that vibe and flourish, with the camera keeping them in center frame. If the viewer briefly looks away, the most shocking visuals could easily be missed. Perkins’ approach is at once refreshing and respectful of viewers who commit. (Quinn Hough)

“Bay of Blood”

To have pioneered the “body count” horror movie is arguably a dubious distinction for any filmmaker to achieve. But it’s true: Mario Bava’s 1972 “Ecologia del delitto” (“Ecology of Murder”) first retitled “Twitch of the Death Nerve” for U.S. distribution, now known though the English-speaking world as “Bay of Blood,” was a direct, documented influence on “Friday the 13th.” “Bay” is hardly the first Bava picture to feature multiple murders; the baroque giallo “Blood and Black Lace” and the pop-art Agatha Christie variation “Five Dolls For An August Moon” are pretty corpse-heavy. But this picture, in which a series of seemingly senseless murders play out against a land-development scheme in a pristine bay community, finds Bava working in a visually modernist mode that’s both chilly (the decorative glass in the first scene between characters Frank and Laura anticipates Fassbinder’s “Chinese Roulette”) and messy (the violence is unusually grisly and bloody for Bava at this time). And the actual storyline has enough cynical twists that the film instantly upends the genre it invents. A too-infrequently-acknowledged great. (Glenn Kenny)

It may be stretching the definition of “underrated” to include a film widely revered as a genre classic (it’s been on lists of the best horror movies ever made, correctly), but with the general reluctance to watch anything made before 1990 seeming to grow with every passing year, I’m going to take this chance to urge you to check this out. Just trust me on this. Sure, it’s “old,” but there are few films ever made that will send a chill up your spine quite like “The Innocents,” an adaptation of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw that plays with the haunted house subgenre in ways that are still influencing the genre. If you loved "Hereditary" or Netflix’s “The Haunting of Hill House,” you will respond to this one too. I guarantee it. It’s one of my favorite movies, regardless of genre. (Brian Tallerico)

“Halloween III: Season of the Witch”

Figuring that he said all that he could about mad slashers stalking babysitters with the first two “Halloween” films, John Carpenter hit upon the idea of an anthology of unrelated horror films to be released under the “Halloween” banner. Unfortunately for him, when gorehounds turned up to see what promised to be the latest Michael Myers kill spree and were instead confronted with a story of a madman (Dan O’Herlihy) planning to play the nastiest joke imaginable on the kids of America by frying their brains with the help of popular masks, a relentless ad campaign and a stolen Stonehenge rock, they felt as if they had been the victims of a cruel trick. In fact, the film (co-written by Nigel Kneale, though he demanded his name be removed from the credits) is actually a real treat—sort of an adult version of “Goosebumps” that is often bizarre, occasionally gross, goofy and nihilistic in equal measure and, thanks in no small part to the performances by O’Herlihy, Tom Atkins as the increasingly hapless hero and the enormously likable Stacy Nelkin (one of those '80s-era actresses who never quite had the career that they deserved) as the heroine, and hugely entertaining to boot. And hey, it even features a cameo from Jamie Lee Curtis for good measure. (Peter Sobczynski)

“Razorback”

From the mind of Russell Mulcahy, Australia's rockstar expat and the creator of the music video as we know it, comes "Razorback," a sarcastic industrial punk night terror. In the film, TV's Gregory Harrison heads to the outback to look for his missing wife and finds a tusked, godless daemon. Shockingly the local psychos (David Argue and Chris Haywood, the platonic ideal of deranged outback bogan) in the Mad Max truck who waylaid here aren't solely responsible for his wife's disappearance; there's a boar the size of a shipping container feeding on the unlucky.

The animal attack genre is a time-honored Australian tradition (“Long Weekend,” “Dark Age,” “Black Water,” “Bait,” “Rogue”) and “Razorback” is the best of the best. Mulcahy directs like a man who's just experienced a bizarre accident like a superhero with the power to shock the eyes and ears with profound style. He'd never quite live up to the promise of his debut, but who could possibly? “Razorback” is a 95-minute electrical storm, a bloody, hairy, blue-filtered miasma, and a quick-witted, deliberately outsized fracas. (Scout Tafoya)

“The Faculty”

"The Faculty" has one of the most star-studded casts in a horror film. Not bad for B-grade teenage box office bait, and it takes the "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" motif to high school and uses social status and loneliness as a means to attack our protagonists. Like all great horror, it's a film about people and this movie's horror subject is the social hierarchy of high school. Josh Hartnett is the bad boy, cocky, arrogant, muscle car driving smart ass. He's a young Harrison Ford, which may explain why the two clashed so heavily when they both starred in "Hollywood Homicide" years later. He turns the film into his own action flick at points, and never before have you ever wanted to be a drug dealing high school bad troublemaker—and he's just one quarter of our magnificent and heroic protagonists. Aliens never had a chance against Hartnett, Clea DuVall, "Animal Kingdom"'s Shawn Hatosy and Jordana Brewster. (B.J. Bethel)

“Lake Mungo”

“Death takes everything eventually. It’s the meanest, dumbest machine there is, and it just keeps coming.” So says grieving mother June Palmer in Joel Anderson’s bone-chilling Lake Mungo. Death and grief are at the heart of Anderson’s effective found footage flick, which presents itself as documentary about a family in crisis. When Australian teenager Alice Palmer drowns during a swimming excursion, her family begins to suspect the girl’s ghost is haunting their home, and attempt to investigate. The specter haunting the frames of Lake Mungo never leaps out shrieking in a jump-scare. It never attacks anyone, or acts the least bit malevolent. And despite all that, Lake Mungo is terrifying. The looming horror of death, and the inevitability of it all, is impossible to break away from here, and the end-result gets under your skin, leaving you in a state of abject, inescapable fear. As June Palmer says, “It just keeps coming.” (Chris Evangelista)

“Bone Tomahawk”’s structure is that of a classic Hollywood Western, with four men (Kurt Russell, Richard Jenkins, Patrick Wilson, Matthew Fox) riding out in search of a woman kidnapped by vicious troglodytes (not Indians, so we’re told), but its flavor is more in the literary vein of an Algernon Blackwood story. A mesh of sadist and humanist, director S. Craig Zahler has a talent for making all his players endearing before prodding them into an inferno that undercuts the assurances of hope, the pretenses of enlightened civilization engulfed by ageless chthonic shadows. The film’s a fearful projection of sexual and familial anxieties, A Bright Hope being a town where women keep men in line, while what we see done to people in the troglodyte den perhaps constitutes the most hellacious representation of ritualized sexual cruelty in recent movies. A happy ending can’t cleanse our eyes of what we’ve seen. “Bone Tomahawk” is romantic, but it just as much feels evil, exuding the feeling of campfire tales that unsettle the imagination in childhood, such as most horror stories no longer provide us in adulthood. (Niles Schwartz)

“Audition”

"Audition" is a 1999 emotional revenge flick for any woman who's been told she needs to find her inner geisha. The title of both the movie and the Ryū Murakami book (オーディション ) comes from a ploy that could easily be pulled from the lecherous Hollywood directors playbook. Widower and documentary director Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi) has not gotten back into the dating game since the death of his wife. His friend, Yoshikawa (Jun Kunimura), suggests that Aoyama hold auditions: The women think they're trying out for a film, but in actuality, they're auditioning to be Aoyama's main squeeze. Aoyama focuses in on a beautiful shy woman haunted by childhood abuse, Yamazaki (Eihi Shiina). Although the director Takashi Miike is known for his scenes of extreme violence, "Audition" has a subversive subtly. Besides Yoshikawa's warning words (Daisuke Tengan wrote the script), Miike provides some visual foreshadowing before the gore. There's something delightful about the twist. (Spoiler alert) Yamazaki's fatal flaw? She's a literal femme fatale. The Murakami and Miike cinematic memo to the world: Besides the geisha, Japan was the home of Masako Hojo, Sada Abe, Sugako Kanno and Zeami's Noh play, Dōjōji (道成寺). (Jana Monji)

“The Prince of Darkness”

At the height of Satanic Panic and its association with rock that was harder than Bon Jovi, Alice Cooper’s casting in a movie about the coming of the Devil was very on-brand for both the singer and director John Carpenter. Set in the late ‘80s, the film follows a group of scientists studying an extremely ancient container holding a green, gravity-defying liquid. Those geeks are actually what make this movie so effective, because they root us in reality. They’re dealing with something that, to us, is clearly paranormal, but they still try to understand it through a scientific lens. The evil eventually comes, but it’s a slow build. The spooks are partly delivered by those who become possessed and do the Devil’s bidding. But most of the horror stems from the notion that if this were to happen, science and religion alike would be woefully unprepared. (Olivia Collette)

“The Last Exorcism”

Arriving at the height of the found-footage horror craze, "The Last Exorcism" was well-received by critics and, with its miniature budget, did well enough at the box office to produce an inferior, unnecessary sequel. Sadly, though, director Daniel Stamm's intelligent and character-focused horror film has all but disappeared from the public's memory. It deserves better, especially since it gives us something that we don't typically associate with horror movies: great performances. The first comes from Patrick Fabian, as a charlatan minister who decides to confess his phony exorcism practices to a documentary crew. The second comes from Ashley Bell, who might be possessed by a demon. The story is familiar, yet Huck Botko and Andrew Gurland's screenplay spends time establishing the crisis of conscience—and then of faith—of its protagonist, as well as the discomforting dynamics of the family of the teenage girl. That attention to detail elevates the film above its genre trappings. (Mark Dujsik)

“The Eye”

I first saw the Pang brothers' 2002 film “The Eye” recently after having major eye surgery, and so was already half in the tank for any horror movie involving eyes in any way. Even if that wasn't the case I would still stump for it as stylishly executed and emotionally gripping supernatural horror. The Pangs add elements of the otherworldly with elegant patience, content to let the trauma of the protagonist's eye surgery stand on its own in the early going. Gradually, and mostly purely through canting angles, cutting judiciously, and particularly by manipulating focus to literally blur the distinction between the natural and supernatural worlds, we emerge into a world in which fully manifested ghosts haunt the increasingly terrified heroine, played with precision and sensitivity by Angelica Lee. The film builds to a climax that's at once tragic and, paradoxical though it may sound, fatalistically reassuring. (Danny Bowes)

For its first half-hour or so, Bobcat Goldthwait’s 2013 gem plays like an endearing comedy, as a young couple (Alexie Gilmore and Bryce Johnson, both excellent) encounter the quirky inhabitants of Willow Creek, a mountain community famous for its alleged sightings of Bigfoot. The tone shifts dramatically during an 18-minute unbroken take of the lovers huddled in their tent, as eerie noises creep closer to their makeshift campsite. Taking inspiration from the scariest sequence in 1999’s horror landmark “The Blair Witch Project,” where the voices of children giggle outside the filmmakers’ tent, Goldthwait creates a different sort of immersion by keeping us focused on the actors’ faces, as they gradually morph from incredulous to paralyzed with fear. It is the condescension with which the couple view their surroundings that dooms them in the end. When a threat is treated like a joke, it is guaranteed to get the last laugh. (Matt Fagerholm)

"Night of the Living Dead" (1968) and "Dawn of the Dead" (1978) are undisputed classics, and "Day of the Dead" (1985) has plenty of defenders. However, George Romero's fourth zombie apocalypse movie, "Land of the Dead" (2005), is the one that gets left out of the conversation right before it turns to fast zombies vs. slow ones. This is too bad, because Romero's gore-laden musings on Bush-era income inequality are sadly his most prescient, which is really saying something for a series that always used heavy amounts of social satire to underpin all that cannibalism.

While filmed in Canada instead of Pittsburgh, Romero's hometown is never far from his mind. "Land" takes place in a city protected from walking corpses by rivers on three sides and walls all around where the ultra-rich live in a Trump Tower-type complex called Fiddler's Green, and everyone else is subjected to Dickensian squalor. The zombies get smart this time around, the walls fall, and fingers are munched on. With “Land,” Romero puts forth the radical (even for him) proposition that humanity might not be worth saving, and true liberation can only come from joining the undead horde. With Dennis Hopper (whom Ebert even refers to as “the Donald Trump of Fiddler's Green” in his three-star review of the movie), John Leguizamo and Asia Argento, “Land” is the only one of Romero’s zombie movies with stars you’ve heard of, but don’t let that deter you. Each one enhances the subversion of Romero’s last great living dead epic. (Bob Calhoun)

“Session 9”

One of the most unfortunately neglected, psychological thrillers of the last decade, Session 9 quietly showed up in theaters in the summer of 2001—practically released a month to the day before 9/11 happened—and was mostly forgotten after that. A crew of working joes (which includes Peter Mullan, David Caruso, Josh Lucas and Larry Fessenden, who has directed many scary movies himself) descend to the abandoned Danvers State Mental Hospital to remove asbestos. Needless to say, things immediately get creepy and unsettling for these guys—and that’s even before one of them discovers taped sessions with a patient who suffers from dissociative identity disorder. (Fans of "Split" will definitely dig this.) After making a couple of rom-coms, Brad Anderson made a risky detour into terror land and, despite the lack of box-office receipts, Session works quite well. Anderson took his low-budget means (it’s one of the first films to be shot on 24p HD digital video) and created an impressively eerie piece of blue-collar horror that’s more about mood and atmosphere than gore and cheap scares. (Craig Lindsey)

“May”

Directed with unnerving confidence by Lucky McKee, the quirky horror film "May" delivers the goods. I'll never forget showing it to a friend, a hardened horror fan who introduced me to George Romero, only to have him recoil in terror and beg me to turn it off. Once you get past imagery like blind children crawling over broken glass, there is an affecting story of a strange woman who craves acceptance she will never find. Angela Bettis is unforgettable as May, a veterinarian's assistant whose obsessions with anatomy is downright homicidal. She meets two people who like her strange nature, but only up to a point. The tragedy of "May"—and it is a tragic film—is that under all her violent impulses, the hero just wants what everyone else has. May finds some peace in the final shot, but it's only pieces of what she needs—literally and figuratively. (Alan Zilberman)

The less you know about it before you see it, the more you will enjoy “Coherence,” a nifty thriller that craftily makes the most of its micro-budget with a deliciously mind-bending story. As in all great thrillers, the really scary stuff here is not what’s happening outside of the characters, but what it does to the people on the inside, and to us in the audience. Writer/director James Ward Byrkit, who wrote “Rango” and created the visual design for the “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies, wanted to take some time away from blockbusters and create something small and intimate. He literally shot this movie in his living room.

The set-up is simple. Eight friends get together for a dinner party that seems perfectly ordinary, until something happens and someone says he’d better go outside and see what it is. We’ve all seen enough movies to know that this is probably not a great idea. What happens next is not a plot twist but a plot Rubik’s Cube, an ingeniously constructed infinite regression of meta-realities. To say any more would be to spoil the movie’s best surprises. So I’ll just suggest that you watch it—and then when you’re done, go back to watch that “ordinary” dinner table conversation at the beginning again and see how neatly it sets out what’s ahead. (Nell Minow)

“The Blob”

David Cronenberg wasn’t the only director to twist 1958 sci-fi into stinging 1980s commentary. Chuck Russell’s 1988 remake of “The Blob” casts the very hungry Jell-O based alien life form as the harbinger of an apocalypse brought on by a hawkish government and rogue religious zealotry. Russell’s script, co-written with Frank Darabont, blends Cronenberg’s penchant for body horror with John Carpenter’s distrust for authority and is unrepentant in ways the best horror movies are: No character is safe and many of the deaths are brutally unfair. This Blob has a taste for the helpless and the hopeful, from the bratty little kid who tearfully tries to repent to the diner waitress (a heartbreaking Candy Clark) who picked the wrong night for a long-anticipated first date. The gory kills are as mean and clever as the casting of nice-guy Joe Seneca as the evil government agent. The juvenile delinquent heroes played by Kevin Dillon and Queen of the Saw franchise Shawnee Smith feel air-lifted from the 1950’s, which makes them—and the movie—all the more effective. (Odie Henderson)