He will always hold a place in history as the first black director nominated for the Academy Award, and yet it feels like John Singleton was still underrated. "Boyz N the Hood" made him a star, but there's a power to his other works from "Poetic Justice" to even "American Crime Story: The People v. OJ Simpson" that never quite got the critical acclaim it deserved. There are many reasons to be deeply saddened by his passing at far too young an age, but one is that the worlds of film and TV have lost someone who wasn't anywhere near done with his career. We asked our writers to offer their thoughts on what John Singleton meant to them after Odie Henderson's gorgeous tribute and this collection of Roger Ebert's writing on Singleton's career.

CHAZ EBERT

John Singleton’s death at age 51 hurts. I still remember his young eager face at the Cannes Film Festival in May of 1991. He was only recently out of film school and yet was in the South of France with his first passport to screen his first motion picture at the mother-of-all-festivals. The head of Columbia Pictures, Frank Price, told Roger that John was so passionate in his defense of his screenplay that he reminded him of Steven Spielberg. John persuaded Price to allow him to direct it. Right from the beginning as a director John had something to say, and he had a unique style. His tagline for his movie was "Increase the Peace."

"Boyz N The Hood" was screened not in the major competition, but in Un Certain Regard, where some say the best commercial films are exhibited. When the lights came up the standing ovation was so long and so rousing that we all knew a new bold director had been born. This was astounding to John. He said he made a film specific to South Central LA and had no idea it would be heralded thousands of miles away by people who knew nothing about the hood. As Roger said, the specific becomes the universal. When you try to make a film to please everybody, you usually end up pleasing nobody. John didn’t try to please everybody, his films hewed close to his African-American roots, and paradoxically pleased most. "Poetic Justice," "Higher Learning," "Baby Boy," "Rosewood" —all presented authentic aspects of black culture that John knew and interpreted beautifully for the screen. He was groundbreaking because he believed so firmly in what he was doing.

That year at Cannes was one of the best in memory. We all went out dancing every night, and John thrilled in the fact you couldn’t walk down the street without bumping into Wesley Snipes, or Mario Van Peebles, ("New Jack City"), Bill Duke ("A Rage in Harlem"), Spike Lee ("Jungle Fever"), Robert Townsend ("The Five Heartbeats"), or even Madonna ("Truth or Dare"). But there was no doubt that the loudest trumpet that summer was for John. Roger predicted a Black New Wave of films, and indeed during that year there was also Julie Dash with "Daughters of the Dust," Matty Rich with "Straight Out of Brooklyn," and others. John was as eager to talk about the films of other filmmakers as he was of his own. Over the years he developed a reputation for being magnanimous in helping out other filmmakers. You would hear stories of his generosity when speaking on college campuses giving tips about directing, but encouraging students to find their own voices.

The list of actors either introduced by John in his movies or whose careers were magnified by them are impressive: Taraji P. Henson, Cuba Gooding Jr, Lawrence Fishburne, Regina King, Tyrese Gibson, Ice Cube, Morris Chestnut, Janet Jackson, Ving Rhames and Tupac Shakur. John was hoping to direct a movie about Emmett Till. Taraji P. Henson was to portray Till's mother, Mamie Till Mobley.

John stayed in touch over the years and I was grateful to him for reaching out to me after Roger’s death, and for agreeing to attend by Google Hangout, a “birthday celebration” for Roger in 2014. That video is embedded below.

I send my deepest condolences to his parents Sheila Ward and Danny Singleton; and to his children Justice, Maasai, Hadar, Cleopatra, Selenesol, Isis, and Seven. I am hoping that John is resting in Bliss in Heaven's Hood.

SHEILA O’MALLEY

I saw "Boyz N the Hood" during its first theatrical run in a packed movie theatre in Philadelphia. To date, it's one of my most memorable movie-going experiences: the movie arrived with buzz all around it, and the audience—including me and my boyfriend —was hyped into the stratosphere, before even the lights went down.

There's one sequence in "Boyz N the Hood" which has wiggled its way into my subconscious, the way scenes or moments in film sometimes do. They become part of the texture of your life, how you think, the references you make. Moments like the "dueling anthems" scene in "Casablanca", or the husband-and-wife reunion scene in "Sounder," or the painful Fredo-Michael scene in "Godfather II ("I'm your older brother, Mike!"). Your “moments" may vary, but these are some of mine.

In the opening sequence, four young boys (Tre, Ricky, Doughboy and Chris) walk to an alley between the houses to see a dead body lying in the weeds (a callback to Stephen King's novella The Body, and the film adaptation "Stand By Me"). Ricky's dad has given him a football, and he carries it with him, even though Doughboy tells him he should leave it at home (for reasons which become obvious in the scene). An older boy comes by and basically tricks Ricky into tossing the football over. The older boy won't give it back, and instead starts to toss it around with his friends. Violence, always shimmering in the air in "Boyz N the Hood," breaks out, and the four children limp away, sans football.

But then, one of the older guys, shirtless, intimidating, a man not a boy, calls out to Ricky's retreating dejected figure, "'Ey! Hey, little man!" Ricky turns back, and the guy tosses him the football, returning it to its rightful owner.

So much of directing is knowing what event it is that you are filming, the event's specifics and undercurrents, what happens but also what it signifies. Singleton's touch throughout is so sure, so certain (astonishing for a 23-year-old first-time director), and this sequence is one of the best examples.

I'm struck by how it's edited. Where he cuts, when he cuts ... it's so clear. But you can't create a sequence like this solely in the editing room. You have to have a firm structure beforehand (especially in a low-budget film). Singleton was prepared. The scene unfolds with laser precision. Watch for the glimpses we get of the older guy who eventually gives Ricky back his football. Singleton doesn't "punch it up" with cut-ins to him or close-ups, but he's there in the background, tossing around the football, but you can sense his deeper awareness of what's happening, the football is not his, the football means something to the child walking away.

It is the character's only scene. But you remember him. He sticks. The moment sticks. Singleton planned the sequence so carefully, he knew how to stage manage a complex scene with multiple characters, a scene involving a fist fight, a dead body, and a small exhale of catharsis when the older guy steps in, making things right. Singleton knew the event. He knew its importance, and he got it right.

I think about that moment all the time.

PETER SOBCZYNSKI

It is almost impossible to properly convey the explosive impact that John Singleton’s hypnotic debut film “Boyz N the Hood” made when it hit theaters during the summer of 1991. Amidst such heavily-hyped blockbusters as “Terminator 2: Judgement Day,” “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves” and the like, it was Singleton’s low-budget work loosely inspired by his own days growing up in south-central Los Angeles and featuring a cast headed by Laurence Fishburne and filled out by such then-unknown big-screen quantities as Cuba Gooding Jr., Morris Chestnut, Angela Bassett, Nia Long, Regina King and Ice Cube that made the biggest waves of the season.

For many members of the criminally underserved African-American moviegoing audience, it provided them with a cinematic depiction of their day-to-day existence that was neither candy-coated nor overtly exploitative and made with the kind of assured technical skill that put most of that year’s multiplex efforts to shame. The end result was a major box-office hit, launched its young cast members to stardom and not only announced Singleton as a talent to watch but made him both the first African-American and the youngest person ever nominated for the Oscar for Best Director. (He was also nominated for Original Screenplay.)

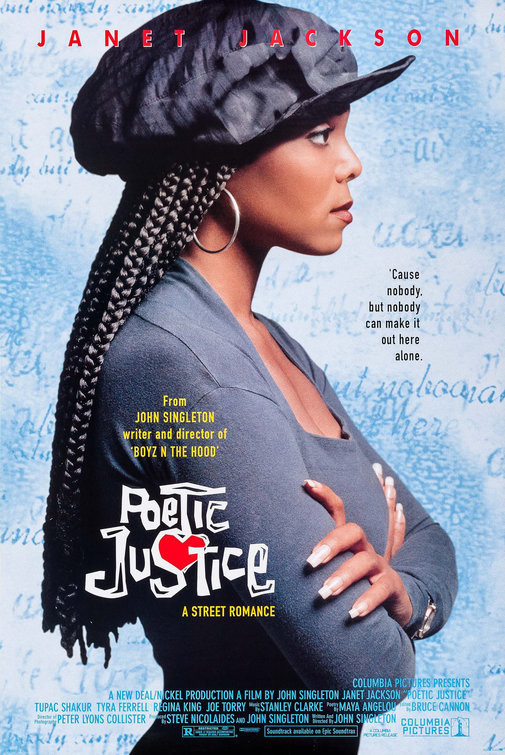

Instead of resting on his laurels from such an achievement, Singleton decided to expand his ambitions with his follow-up effort by taking perhaps the one key piece of criticism regarding his debut—the depiction of his female characters—and using that as a jumping-off point for “Poetic Justice” (1993), a film centered around a female protagonist (Janet Jackson) that was decidedly different than its predecessor. While that film, and subsequent works like “Higher Learning” (1996), “Rosewood” (1997) and “Baby Boy” (2001), may not have had the impact of “Boyz N the Hood,” they nevertheless found him using his clout to try to find unique stories to tell and if they sometimes stumbled along the way, they were stumbles borne of ambition rather than laziness.

Later on, perhaps in response to the realities of the American film industry, he began to switch to less personal fare with projects like a remake of “Shaft” (2000), “2 Fast 2 Furious” (2003) and “Four Brothers” (2009) and episodes of such television shows as “Empire,” “American Crime Story” and “Billions” and while they may have lacked the punch of his earlier films, they were skillfully made. Beyond his own personal cinematic output, perhaps his greatest legacy as a filmmaker can be found in the number of people who saw films like “Boyz N the Hood” and “Poetic Justice” and were subsequently inspired by his example to pick up cameras and tell their own stories on their own terms. Singleton’s own output may have been tragically cut short, but his influence will no doubt be felt for generations to come.

Q.V. HOUGH

John Singleton’s first three films schooled a kid from small town Minnesota. In the summer of ’91, “Boyz N the Hood” released just days before my older brother left for U.S. Army basic training in Waukegan, Illinois. At 11 years old, I didn’t quite understand the larger implications of Singleton’s script and filmmaking, but the central storyline of trust, loss and brotherhood resonated deeply. My parents had divorced a years few years prior, and my big bro’s departure left another void. As a viewing experience, “Boyz N the Hood” felt exhilarating upon a first watch, and it opened my eyes to real-life scenarios that I hadn’t previously considered. In Barnesville, Minnesota— population 2,006—only three black people lived in the community, with one of them being a friend and classmate from around the block. Tre. Doughboy. Furious. The “Boyz N the Hood” characters felt real, and I had to know more. And that Ricky scene … as they say in the Upper Midwest, “UFFDA.”

By 1992, Ernest Dickerson’s “Juice” had a similar effect, most notably because of Tupac Shakur’s performance as Roland Bishop. When Singleton released “Poetic Justice” in 1993, the casting of both Shakur and Janet Jackson meant that I needed a VHS copy ASAP. Even though I couldn’t fully understand the underlying themes of race, romance and violence in “Poetic Justice,” characters like Justice and Lucky left a mark; a testament to Singleton’s storytelling abilities.

“Higher Learning” released in 1995, and this particular film checked many boxes. For one, it was a John Singleton film—the experience of “Boyz N the Hood” and “Poetic Juice” created some VHS hype. Two, history had become a favorite subject of mine, and the film’s collegiate backdrop allowed for an immersive experience thanks to Singleton’s sociopolitical themes. Plus, the diverse cast appealed to my cinematic and musicals interests: Ice Cube and Busta Rhymes; Kristy Swanson and Jennifer Connelly… and Tyra Banks. Who is Tyra Banks? And that’s the beauty of John Singleton film - there’s always the sense of wanting to know just a little bit more, even though some of it hurts. I lived and died through John Singleton’s films, or at least that’s how it felt back then.

OMER MOZAFFAR

"Boyz N the Hood" was a film with such operatic force that it launched and became the benchmark for a genre. It was so immersed in film history—I still notice more movie references in it—while so potent with political commentary. Then film after film building upon that foundation. Spike and Scorsese come from the New York school. How did Singleton—a kid from South Central LA—do this through the California school of filmmaking?

John Singleton was so comfortable in every interview. His prose reflections were so honest. And, all this while he was just a few years older than me. He was that older brother in the distance who charted a way forward, that I was too timid to follow.

MONICA CASTILLO

I was lucky enough to see John Singleton talk about "Boyz N the Hood" in person at the 2016 TCM Film Festival. For the movie's 25th anniversary, the festival held a screening in the heart of Hollywood at the TCL Chinese Theater and a discussion moderated by film historian Donald Bogle. It was an incredible conversation, and most of what's stuck with me since then were the kinds of stories that were shared in the aftermath of the director's death. He was often told "no" before and during the making of "Boyz N in the Hood." No, he didn't have enough experience. No, he was too young to be this ambitious. No, he wasn't ready to take the lead. Many creatives of color may recognize that chorus of "no" from their own experiences. That night, Singleton shared just a fraction of the warnings and rejections he got as a fresh-faced USC grad working on his feature film debut, and how he listened to none of it. He stuck by his vision in the way that celebrated auteurs do, yet in his lifetime, I don't think he got the respect that big-name directors earn. Singleton broke records as the youngest and first Black director to earn an Oscar nomination, opened doors for other young Black filmmakers, and showed the rest of the industry just how big the divide is between Hollywood and communities of color like the South Los Angeles neighborhood where he grew up. Sadly, that divide did not end in his lifetime, but his work to break barriers for other underrepresented filmmakers must continue.

MATT FAGERHOLM

Before we see anything aside from the Columbia Pictures logo in John Singleton's timeless 1991 masterpiece, "Boyz N the Hood," we hear the sounds of mounting chaos. An altercation erupts, guns fire, and a boy cries, "They killed my brother." Then the first shot arrives, a slow pull-in to the towering letters, STOP, on an every day street sign, articulating the overriding sentiment Singleton aims to convey. Meanwhile, an airplane soars overhead, much like the ones in Alfonso Cuarón's "Roma," oblivious to the circumstances of those living on the streets below. I had never seen this film until the day that Singleton's family announced, in anguish, that they would be taking their beloved father off life support, following a stroke at age 51. He was only 23 when he helmed "Boyz N the Hood," his debut feature, anchored by the script he insisted on directing because it was his life.

He made history as the youngest filmmaker ever to earn an Oscar nomination for Best Director, in addition to his nod for Best Original Screenplay, yet watching the film today, it seems criminal that the film wasn't included in more categories, especially Best Picture. Cuba Gooding Jr. has never been more vulnerable onscreen than he is here, playing a tender hearted soul who becomes enraged at the injustice of having to live in a perpetual war zone, which we hear rumbling outside like an encroaching storm. As his father, Laurence Fishburne delivers an extraordinary monologue about why liquor stores and gun shops are placed on every corner of a black neighborhood: "They want us to kill ourselves." It was a scene between him and Gooding Jr. late in the picture that caused me to break down, as the father pleads for his son to do the right thing, only for him to realize that the young man must come to that decision on his own. There are echoes here of "Stand by Me," from the opening prologue where four young friends walk along a railroad track to investigate a dead body, to the wrenching end coda where one character, whom we've grown to love, evaporates before our eyes. If you haven't yet gotten to see this miracle of cinema, seek it out immediately. It is one for the ages.

MATT ZOLLER SEITZ

John Singleton was one of the most important filmmakers of my generation, a groundbreaker for both African-Americans and people raised working-class (there are so many wealthy legacies in the industry). He was both the first Black filmmaker nominated for an Oscar as Best Director and the youngest, for his first film, "Boyz N the Hood." It was a classic, descended directly from 1970s films like "Claudine" and "Cooley High," but with a more tragic undertow, and as close to American Neorealism as studio movies get.

As he went on to more films, he continued to tell stories that drew on his experience—most recently as an executive producer and co-director of the first season of "American Crime Story," an epic historical drama (and sometimes a bleak satire) about race & politics in LA, set during the O.J. trial, and equally concerned with the psychic fallout of the Rodney King beating, the acquittal of the officers who did it, and the subsequent rebellion. He was such a personal voice, rooted so powerfully in lived experience. How incredible it was that he rose so far in an industry that was, for a very long time, reflexively hostile to artists like him.