About 20 minutes into Claire Denis's "Stars at Noon," I was convinced that we'd be hearing lusty boos by the end and that Denis had delivered a film maudit. (Here's J. Hoberman explaining the term with regard to Denis's "Trouble Every Day.") The actual reception has been more divided; I heard mostly tepid applause as the credits rolled. But Denis's drama—adapted from a novel by Denis Johnson, and featuring Margaret Qualley as a travel journalist and Joe Alwyn as an oil company consultant who get hot and heavy in Nicaragua—is just about the weirdest imaginable version of that story. Who else casts Benny Safdie as a C.I.A. operative? Or John C. Reilly, who gets a very French "with the participation of" credit, in a one-scene role as a magazine editor?

Initially, it's even difficult to figure out exactly what Qualley's character, Trish, does for a living, and Qualley's airy yet forceful performance makes it even tougher, in a good way, to get a read on her. Trish tells people she's a member of the press, but it's more complicated. A former freelance writer, she is trapped in Central America; short of cash, she dabbles in prostitution. Her tryst with Alwyn's character at a hotel—his skin is so white, she remarks in bed, it's as if she's having sex with a cloud—turns into something like romance as she helps him steer clear of being trailed. It seems a Costa Rican cop is after him. Meanwhile, the shadow of possible American meddling in local affairs looms.

But of course, this is a Denis film, and the plot is secondary to atmosphere (conjured in part by one of her trademark Tindersticks scores) and texture. Here, that texture includes a lot of sweat-beaded skin as the two stars shed their clothes and their Covid masks, not in that order. You can sort of picture an '80s-Hollywood erotic-thriller version of this story, but it's safe to say it would not have featured a sex scene with menstrual blood. That part seems like pure Denis.

Whether the director, who has had more than her share of slights from Cannes and has not been in competition since 1988's "Chocolat," has tweaked the scenario enough to make it interesting is beyond doubt. (The screenplay is credited to her, Léa Mysius, and Andrew Litvack.) Whether she subverts it enough to make a profound movie, let alone a great movie by the standards of the director of "Beau Travail," is less certain. But even in a new genre and on a new continent, Denis's offbeat and personal style is unmistakable.

Asghar Farhadi, the director of "A Separation" and "A Hero," is on the Cannes jury this year, but his presence was felt in the competition all the same. "Leila's Brothers," an Iranian feature from the filmmaker Saeed Roustaee, if anything plays like a Farhadi picture supersized. So heavy with dialogue that it makes Farhadi's scenarios look like Murnau tone poems, it devotes the better part of its two-hour, 45-minute running time to laying out the financial and social motives of the members of an Iranian family.

The unmarried Leila (Taraneh Alidoosti) is convinced that the best long-term investment for her and her four brothers is to open a shop in a mall. But one of her brothers, Manouchehr (Payman Maadi from "A Separation"), is attracted to the idea of getting wealthy faster by taking part in a car-selling scheme. Another, Alireza (Navid Mohammadzadeh), initially positioned is the film's conscience, is skeptical of turning to fraud. Meanwhile, their father, Esmail (Saeed Poursamimi), is willing to pay for a wedding within the extended family to ensure he replaces his recently deceased cousin as the family patriarch. But it may well be that a much wealthier branch of the family is conning him.

That's just the start of it, and while the movie's long, long setup can seem tedious and arid, all the pieces click into place a little more than halfway through during the wedding scene, when everyone's desires are recast or upended. The film's last third is as relentless and swift as the first two-thirds are deliberate. Small mistakes have precipitous consequences. Lies have knock-on effects that ripple through the entire family. It's the first film I've seen from Roustaee, and while initially I thought he needed someone to pare down his script, by the end I was convinced that he knows exactly what he's doing.

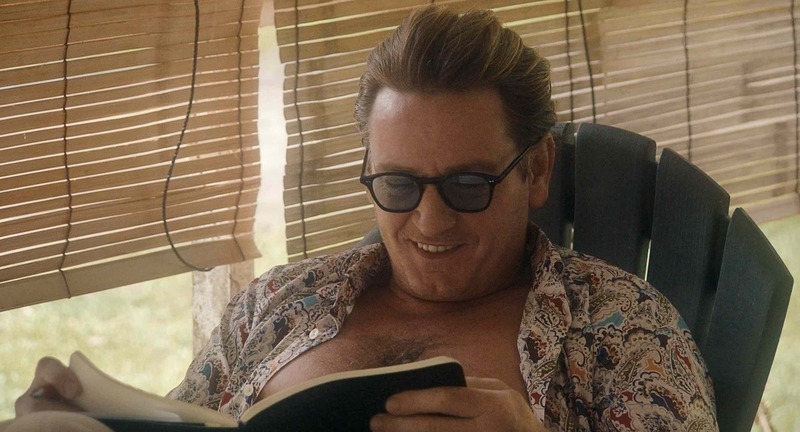

Denis is not the only director at Cannes dipping a toe into something like international-thriller territory. The Catalan filmmaker Albert Serra—a regular Cannes provocateur ("The Death of Louis XIV," "Liberté") in competition for the first time—is here with "Pacifiction" (not a typo for "pacification," but rather a portmanteau of "Pacific" and "fiction"), which has all the outward trappings of an espionage movie. Benoît Magimel plays a dapper French government official in Tahiti; something ominous may be on the verge of happening with nuclear testing. I'll be honest, though: I had no idea what was going on plot-wise most of the time, and that opacity is by design. Serra speaks in the press notes about not wanting to explain things and about trying to keep viewers close to the main character's unreliable headspace—to immerse them in the protagonist's ceaseless, smooth chatter without quite indicating that chatter's relevance to him or to others.

Serra has paced the film, which just like "Leila's Brothers" runs two hours and 45 minutes, for an absolute minimum of urgency and suspense. Instead, he parlays the material (an original story, though you'd be forgiven for assuming it was an adaptation) into something that resembles a "Querelle"-like fantasia or a druggy interlude at the French plantation in "Apocalypse Now." Endless, languorous conversations unfold as a ukulele drones on in the background. The bold colors, the sunsets, and the giant waves of Tahiti looked phenomenal on the big Lumière screen; on a level of aesthetics, it's hard to watch "Pacifiction" and not want to shout "cinema!" Though I do wish I'd felt more engaged, or at least less at sea.

Ben Kenigsberg is a frequent contributor to The New York Times. He edited the film section of Time Out Chicago from 2011 to 2013 and served as a staff critic for the magazine beginning in 2006.