“Dean” is a movie that very clearly came from humane and compassionate impulses. This is particularly evident during the final third of the film, during which the principal characters reluctantly shed their defensive quirks and face up to the issues of grief and loss that have been dogging them throughout the movie.

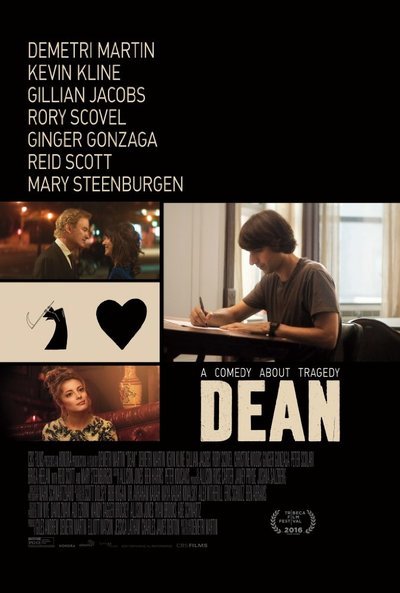

That said, “Dean” is also a movie with which it is easy to find fault, and if you’re a particular kind of person, you’ll find fault with it without even trying too hard. The movie is the directorial debut of Demetri Martin. Demetri Martin of the floppy Beatles-esque haircut (which he’s still rocking at 44, an age at which those Beatles that survived to that age had rethunk their tonsorial stylings more than once) and the wry jokes and the minimalist visual-pun cartoons and the demeanor so relentlessly quiet-hipster-twee that he makes Wes Anderson look like Ozzy Osbourne. Said demeanor is on full display here, as Martin, of course, also stars in his directorial debut, which he also wrote.

The movie opens with the writer/director/star standing at a gravesite with Kevin Kline. Kline and Martin play father and son, and the grave is that of the wife of Kline’s Robert and mother of Martin’s Dean. (Yes, of course Martin plays the title character.) Robert is an engineer—Dean observes of him that every crisis he encounters represents a problem to be practically solved—while Dean is a cartoonist who lives, you’ll never guess, in Brooklyn, one of the nice leafy brownstone neighborhoods rather than the beardo-infested environs of Williamsburg or some such, so I guess that makes some kind of difference.

Father and son are handling loss in their own way. Robert wants to sell his suburban house (the “flight” instinct), which sets Dean right off—what about his memories, his share in the house, which he seems not to have contributed to the mortgage payments on, but never mind. Dean’s way of dealing had begun when his mom had gotten sick. Hoping to demonstrate that he was on a life’s path that would please her, he ill-advisedly got engaged to a woman he had not been ready to commit to. Now the mother has died, the engagement is off, and Dean is acting out passive-aggressively against his ex-girlfriend, against the best friend at whose wedding he makes an ass of himself, and against his father and his house-selling scheme, which he tries to duck by flying out to Los Angeles on a faux-business trip. There he has an awful meeting with some super-miserable Internet bros (one of whom is played by Beck Bennett of “SNL”), and a cute meeting with Nicky, an attractive young woman he embarrasses himself in front of at one of those parties where the East Coast guy discovers that all his friends who’ve moved to California have become self-absorbed monsters.

I know what you’re thinking: wait, isn’t this “Garden State” with the geographics reversed? And aren’t we so over the alienated-guy-meets-you-know-what-kind-of-uplifting-female-character scenario?

Well, sort of, and sort of. Martin’s Dean is certainly sardonic in his anti-macho way (“I can’t bring myself to work with people who call themselves ‘creatives’” is one of the Dean apercus meant to elicit a knowing chuckle from his target demo), and his forlorn qualities are hardly unfamiliar. As for Gillian Jacobs’ Nicky, her appeal does have a certain pixieish quality. There seems to be an inevitability to the Nicky/Dean pairing that’s paralleled across the country in a storyline that find’s Kline’s dad getting intrigued by Mary Steenburgen’s Carol, a real-estate agent who’s helping with the under-protest-from-Dean house sale. Where the movie becomes worthwhile is at the point when the storyline puts up the speed bumps to the happy ending.

Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. He has written for a host of other publications and resides in Brooklyn. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here.

87 minutes

Demetri Martin as Dean

Gillian Jacobs as Nicky

Kevin Kline as Robert

Rory Scovel as Eric