The famed Italian director Franco Zeffirelli, who was both celebrated and reviled for the flamboyant emotions and visuals he brought to his work, died on Saturday, June 15 at the age of 96. Throughout his long career, he brought opera and Shakespeare (to the stage and the screen) in ways that might have made some purists cringe but which proved to be surprisingly popular with the masses for a time, his influence still felt to this day. Off the screen, he lived a life that was sometimes just as operatic—and sometimes as problematic—as his productions. But even past the age of 80, a point when most filmmakers have retired and hit the Lifetime Achievement Award circuit, he was still out there staging plays, mounting operas and even getting himself elected twice to Italian Parliament.

Gian Franco Corsi Zeffirelli was born in Florence on February 12, 1923, the result of an adulterous affair between a silk merchant and a fashion designer. He was exposed to the two forms of art that he would become most associated with at an early age—he was taken to his first opera by an uncle at the age of eight and was educated in the works of Shakespeare by a British tutor as a child. He attended the University of Florence to study architecture but his studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War II, where he fought the Fascists and almost faced a firing squad until—in a twist so outrageous that it would have fit perfectly in one of his films—he was reportedly saved when one of his interrogators turned out to be a heretofore unknown half-brother who secured his release. After the war, he returned to his studies, but after seeing Laurence Olivier’s famous 1945 film of ‘Hamlet,” he shifted his focus to the theater, where he began working as a scenic painter in Florence.

It was there that he made the acquaintance of filmmaker Luchino Visconti, who hired him to work as his assistant and as the set designer for his 1949 production of “A Streetcar Named Desire,” the first one ever staged in Italy. (The two also began a romantic relationship that would last for several years.) Over the next decade or so, he worked regularly in the theater and eventually began directing plays and operas. It was with the latter that he would have his first great success, staging and directing them with a distinctive more-is-more approach that critics sometimes dismissed but which audiences throughout the world embraced. Thanks to a friendship with Maria Callas, he was able to stage a celebrated production of “La Traviata” featuring her in Dallas. Other productions, including a staging of “Tosca” at London’s Covent Garden and a production of Verdi’s “Falstaff” in 1964, would begin a long-running association with New York’s Metropolitan Opera.

When he chose to make his move from the stage to the screen, Zeffirelli, who had worked with the likes of Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini earlier in his career, he did so via his other great artistic love. His first film was an adaptation of Shakespeare’s battle-of-the-sexes comedy “The Taming of the Shrew” (1967) featuring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton as Kate and Petruchio, respectively. Seen today, the film is a little wobbly in spots with its sometimes broad comedic approach, and even though she is ultimately just fine in the role, it is sometimes quite obvious that Taylor is not nearly as adept at handling the language of Shakespeare as Burton. Nevertheless, his instinct to cast the couple when original choices Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni were unavailable—a move that clearly did not thrill studio executives with clear memories of how the duo’s “Cleopatra” went out of control—proved to be inspired both from an artistic and commercial standpoint. The film went on to be a worldwide success, and received much-deserved Oscar nominations for Art Direction-Set Direction and Costume Design.

His next film, which would prove to be the most enduring of his cinematic efforts, was his 1968 adaptation, “Romeo and Juliet.” Over the years, there had been a few screen versions of the play but none were particularly successful, mostly because while it's possible for an older actor to play a younger person on the stage, it's much more difficult to pull that off in front of a movie camera. In the 1936 version, for example, the titular teen lovers were played by the 43-year-old Leslie Howard and the 34-year-old Norma Shearer. Zeffirelli’s inspired notion was to cast actors who actually came close to matching the ages of their characters and wound up hiring unknowns Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey in the leads. (It is rumored that he had at one point considered casting Paul McCartney as Romeo.) The end result was Zeffirelli’s most notable cinematic achievement—his taste for florid dramatic and visual excess fit in perfectly with the tale of outsized emotions he was telling, and while the two stars might not have threatened the stature of the likes of Olivier (who ended up reading the prologue and dubbing in the voice of Lord Montague), they connected with each other and with the teenage audience, who came out in droves to see the film.

Thanks to that younger crowd, the film became the most financially lucrative Shakespeare film of all time to that point, and scored four Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director for Zeffirelli, Costume Design and Cinematography, winning the latter two. Even today, the film's influence continues—it is still shown in schools as a way of exposing kids to the Bard (and no doubt continues to raise a few hackles here and there thanks to the then-surprising brief moment of nudity that was a controversial inclusion back in the day) and when others have attempted subsequent film mountings of the play, they have also made sure to cast younger actors in the leads.

After achieving back-to-back successes with Shakespeare, Zeffirelli shifted to religion for his next couple of film projects. "Brother Sun, Sister Moon" (1973) looked at the life of Saint Francis of Assisi, telling his story as an arrogant youth who elected to serve God by renouncing worldly possessions, and living a life of poverty while trying to get everyone from his family to the Pope to change their ways as well. As with his previous film, Zeffirelli was clearly aiming for the youth market by telling the story of St. Assisi in a way that presented him as a forerunner of the then-current counter-culture movement. (The film even featured music by Donovan.) This time around, however, the results were not nearly as strong. Zeffirelli’s visual style was as sumptuous as ever but seemed weirdly at odds with the man whose story he was trying to convey.

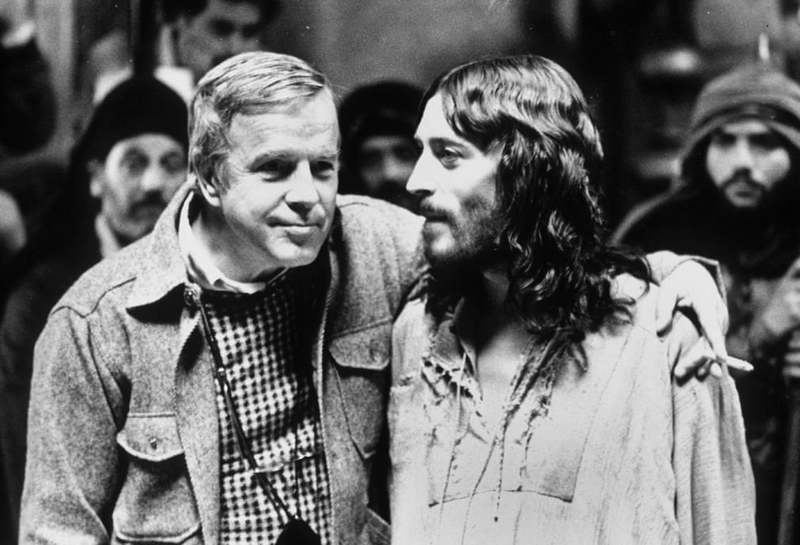

Zeffirelli would have much greater success in tackling religion as his subject with his next project, “Jesus of Nazareth” (1977), a star-studded television miniseries following the life of Christ (played by Robert Powell) that, thanks to his insistence on telling the story in a manner that could be embraced by all faiths, became a massive hit around the world.

Having succeeded in presenting the worlds of opera, Shakespeare, and religion to the masses, Zeffirelli decided to make Hollywood the focus of his next conquest, albeit with far more uneven results. He signed on to do a remake of the old MGM chestnut “The Champ” (1979) in which an ex-boxer (Jon Voight) struggles to continue to raise his young son (then-unknown Ricky Schroder) when his ex-wife (Faye Dunaway) comes back into the picture after being absent for years. Already kind of dated and melodramatic in its original 1931 iteration, the passage of time was not especially kind to the material, and Zeffirelli’s insistence on dialing all the emotions up to histrionic levels did not help matters much and did little to distract from the notion that it was made only to cash in on the blockbuster status of the vaguely similar “Rocky.”

From there, he went on to direct what would become his most infamous film, his critically lambasted 1981 adaptation of Scott Spencer’s best-seller “Endless Love.” With a tale of two impossibly attractive teenagers whose romance teeters dangerously towards obsession with grim results for those caught up in its path, it makes sense that the guy who made “Romeo & Juliet” would be hired to bring it to life. Unfortunately, this one was brought down by a terrible screenplay that completely neutered the power of the book (and I assure you that the book is a stone-cold masterpiece), direction that dialed up the admittedly melodramatic material to often laughable excessive extremes, and by having the star-crossed lovers at the center be played by actors—the then-unknown Martin Hewitt and the then-internationally famous Brooke Shields—who never showed a hint of actual chemistry. Thanks in large part to the drawing power of Shields (whose screen career was nevertheless dealt a near-fatal body blow) and the instantly iconic theme song from Lionel Richie and Diana Ross, the film was a decent-sized hit but pretty much soured Zeffirelli from working in Hollywood again.

For most of the remainder of the Eighties, Zeffirelli’s cinematic output consisted of him bringing famous operas to the big screen in collaboration with the legendary Placido Domingo. The two worked together on “La Traviata” (1982), which earned Zeffirelli another Oscar nomination for Art Direction-Set Direction, “Cavalleria Rusticana” (1982), “Pagliacci” (1982) and “Otello” (1986). He then returned to narrative filmmaking with “Young Toscanini” (1988), a film looking at the early life and career of Arturo Toscanini, played, perhaps inevitably, by C. Thomas Howell. Despite the presence of Elizabeth Taylor in the supporting cast, the film was not so much reviled as it was completely ignored. With his next movie, he returned to his other great love with a film adaptation of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” (1990) and while the film would soon become overlooked in comparison to Kenneth Branagh’s epic take a few years later, it was nevertheless a strong and sturdy adaptation—the casting of Mel Gibson as Hamlet might have seemed like a stunt but his performance was strong (even if he was too old for the part) and he was baked by a fantastic cast that included Glenn Close as Gerturde, Alan Bates as Claudius, and, perhaps inevitably, Helena Bonham Carter as Ophelia.

Although he would continue making films off and on for the next couple of decades, they would never quite hit the heights of his earlier works: There was a performance film of “Don Carlo” (1992) starring Luciano Pavarotti; “Sparrow” (1993) was a romantic melodrama about a 16-year-old novice (Angela Bettis) who returns home from her convent to avoid a cholera epidemic and falls in love with a neighbor boy (Jonathan Schaech); “Jane Eyre” (1996) was a take on the Charlotte Bronte chestnut featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg as Jane and William Hurt as Rochester; “Tea with Mussolini” (1999) was a semi-autobiographical story of a young Italian orphan boy who is looked after by a group of British and American women (including Judi Dench, Maggie Smith, Joan Plowright, Lily Tomlin and, perhaps inevitably, Cher).

His final feature, “Callas Forever” (2002) was a partially fictionalized recounting of the final day of the life of Maria Callas (played by Fanny Ardant), as she struggles to star in a movie version of the opera “Carmen.” Though none of these films would prove to be as big as his first movies, the best of them—including “Jane Eyre” and “Tea with Mussolini” (which was inspired in part by the teacher who taught him Shakespeare as a chid)—demonstrated a flair for cinematic storytelling that did not require visual or emotional pyrotechnics to get his point across. Around this time, he was also awarded an honorary knighthood from the United Kingdom.

If Zeffirelli had at last shown some degree of restraint behind the camera, he could still generate lots of publicity, not all of it good, away from a movie set. On stage, some of his later operas were increasingly criticized for their gaudy excess with a 1998 version of "La Traviata" in particular receiving a great deal of scorn. In 1988, the maker of “Jesus of Nazareth” was one of those protesting the release of Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ,” calling it the result of “that Jewish cultural scum of Los Angeles which is always spoiling for a chance to attack the Christian world.” Along those lines, the deeply conservative Roman Catholic Zeffirelli, who would also serve in Parliament as a member of a right-wing party, would speak out against abortion and gay rights and claimed in a 2006 interview that even though he had been molested by a priest, he didn’t think that he suffered any harm as a result.

Most troubling of all, two of the young actors that he worked with over the years, Bruce Robinson (who played Benvolio in “Romeo and Juliet”) and Jonathan Schaech (who appeared in “Sparrow”), would make accusations of unwanted sexual advances and sexual assault against him. (Years later, Robinson would reportedly use Zeffirelli as the inspiration for the character of the lecherous Uncle Monty for his 1987 cult classic “Withnail & I.”)

These actions and accusations are all deeply troubling, of course, and any attempt to fully grapple with the man and his legacy has to take some of them into account. However, if it is possible to completely separate the personal and the professional, and regard Zeffirelli solely on his artistic output, one finds the kind of artist that one rarely encounters these days—the kind who, at his best, was cheerfully willing to swing for the fences with material (that would have given most filmmakers pause) and did so in an undeniably unique fashion. His work may have fallen out of fashion in later years, but for his ability to make grand opera and the works of the Bard accessible to audiences that might have otherwise shunned them, he will always and justifiably be remembered.

Peter Sobczynski is a contributor to eFilmcritic.com and Magill's Cinema Annual and can be heard weekly on the nationally syndicated "Mancow's Morning Madhouse" radio show.