Now streaming on:

A group of children with no cares at all, free and reckless, run through thick jungle growth, their feet splashing into the ocean waves crashing on the beach, their bodies chasing a train making its way along the water’s edge. Their outfits are a riot of color, and their play-acting is of a wedding, with one child dressed as a groom in a black suit and the other in a crimson red and gold sari, face smudged with lipstick and eyeliner. But a closer look reveals that the groom in this game is a young girl and the bride is a young boy, and the innocence of their imitation of the grownup world is swiftly and summarily destroyed by the rigidity of adult thinking. “Looks like you have a ‘funny’ one here,” a male relative says of the boy in the sari, and the crushing dismissiveness and casual prejudice of that statement guides us into the world of “Funny Boy.”

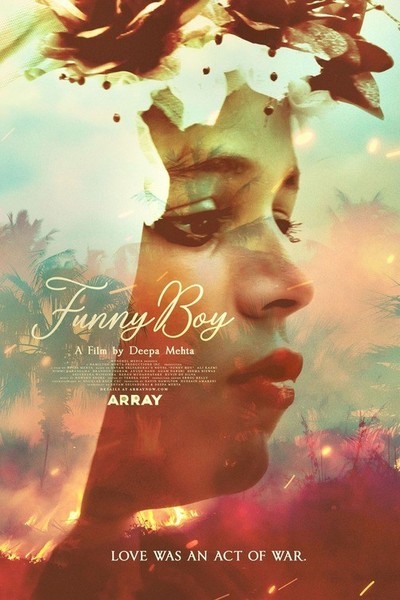

A coming-of-age story set in Sri Lanka during the leadup to the decades-long Sri Lankan Civil War, “Funny Boy” is strongest when it considers how heteronormative gender roles and patriarchal thinking quash individual desire and expression. Characters aren’t as nuanced as they could be, yet vivacious performances from cast members Arush Nand and Agam Darshi elevate the archetypes for which they’re responsible (“girly” boy and unruly woman, respectively). But as an exploration of the myriad factors driving the ongoing conflict between Sri Lanka’s two primary ethnic groups, the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils, “Funny Boy” too often makes the most predictable narrative choice. Viewers with an awareness of the war—the Sinhalese-led pogroms against the Tamils, or the Tamil Tigers’ guerrilla tactics—will often be able to guess where certain scenes or character introductions are leading. That’s not to say that “Funny Boy” is some sort of puzzle to be unlocked, but that the film often depicts its characters and historical events so broadly that the cultural divides in Sri Lanka or the negative effect of traditional thinking regularly go unexamined. Without that follow-up, “Funny Boy” often lacks impact when it needs it the most.

Beginning in Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, in 1974, two years after the island nation finally shook off British control, “Funny Boy” follows a well-to-do Tamil family and their middle child, eight-year-old Arjie (played first by Nand and then later, when the character is a teenager, by Brandon Ingram). To Arjie’s mother (Nimmi Harasgama), her son is creative, musically talented, and adventurous; to his father (Ali Kazmi), however, his “funny” behavior is a cause for concern. No one ever says the word “gay,” but that’s obviously the fear here, so all-consuming a response by Arjie’s father that everything his son does is a problem. “Why does everyone say I’m ‘funny’? What does that mean?” Arjie asks his parents in one of the film’s most heartbreaking scenes, but his father will not budge on trying to expunge all perceived femininity from his son. Arjie will play cricket, Arjie will pray more, and Arjie will grow up to be the man his father wants him to be.

Arjie’s only ally is his aunt Radha (Darshi), who returns from college in Toronto to the judgmental family who hasn’t changed one bit in her absence. Forced into an arranged marriage against her will while in love with another man, Radha becomes Arjie’s closest familial supporter: encouraging his passion for music and dance, painting his toenails (“a joyful secret,” she calls the berry-colored polish she applies for him), and drawing him into her illicit romance with a Sinhalese man by asking him to deliver letters between them. What happens to Radha, and the choices she makes as violence between the two ethnic groups grows, changes Arjie’s path forward. When “Funny Boy” jumps ahead in time to Arjie’s teenage years attending the Christian boys’ school Victoria Academy, the political situation is more fraught. Bullying at the school plays out entirely between ethnic lines. Arjie’s father, who now runs a posh resort, offers safe haven to a family friend, Jegan (Shivantha Wijesinha), who used to be a Tamil Tiger. And when Arjie locks eyes with Shehan (Rehan Mudannayake), a Sinhalese classmate who quotes Oscar Wilde and has posters of David Bowie hanging in his bedroom, the memory of what happened to Arjie’s aunt when she fell in love with someone despised by her family is never far from his mind.

“Funny Boy,” especially in its second half, is trying to tell two stories at the same time: an intimate portrait of Arjie and his growing understanding of his sexual identity, and a grander story about the Sinhalese/Tamil violence and how those divisions caused thousands of Sri Lankans to flee the country. Each of these subplots has some insightful elements, but they are so tonally mismatched, and the latter in particular relies on such unexpected character turns, that “Funny Boy” never achieves a real balance. Mehta’s script too often skips over the details or repeats concepts already introduced. There’s no sense of what Arjie dreams of or wants for his own life; a recurring plot point about Arjie not liking sports isn’t enough characterization. Arjie’s posh mother suddenly sympathizes with the motives and tactics of the Tamil Tigers, a commiseration that comes out of nowhere. There are allusions to the economic differences that drive the divide between Sinhalese and Tamil, but Mehta backs away from engaging with them by positioning Arjie and Shehan as equally wealthy and by folding Jegan into Arjie’s affluent family. That refusal to really dig into the dispute shortchanges “Funny Boy,” making it fall into an imbalanced pattern in which the shock-and-fear aftermath of violence is given more attention than its causes.

Some of these disconnects might be caused by Mehta’s changes to the source material. Her removal of certain chapters, including a trip Arjie takes to the Sri Lankan countryside and his friendship with Jegan, seem to remove most of the character’s interiority. As a result, too much of the narrative just seems to float, without any guiding motivations. The lack of a frame is exemplified by Mehta's preference to replace Nand in certain scenes in the first half of the film with Ingram, and vice versa in the latter half. The visual trick distracts more than it enlightens. If “Funny Boy” were being told by the perspective of an adult Arjie looking back on his life and realizing the childhood moments that informed his adolescence, that would justify this rejection of linearity. But “Funny Boy” falters when trying to link together the personal and political, making for a well-intentioned film that never delivers much depth.

Now available on Netflix.

Roxana Hadadi is a film, television, and pop culture critic. She holds an MA in literature and lives outside Baltimore, Maryland.

109 minutes

Arush Nand as Arjie (child)

Brandon Ingram as Arjie (teenager)