Now streaming on:

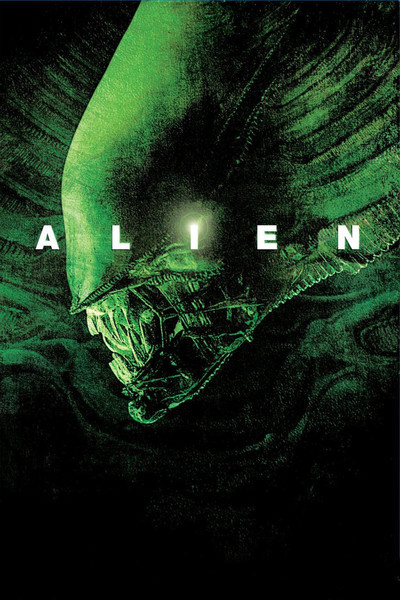

At its most fundamental level, "Alien" is a movie about things that can jump out of the dark and kill you. It shares a kinship with the shark in "Jaws," Michael Myers in "Halloween," and assorted spiders, snakes, tarantulas and stalkers. Its most obvious influence is Howard Hawks' "The Thing" (1951), which was also about a team in an isolated outpost who discover a long-dormant alien, bring it inside, and are picked off one by one as it haunts the corridors. Look at that movie, and you see "Alien" in embryo.

In another way, Ridley Scott's 1979 movie is a great original. It builds on the seminal opening shot of "Star Wars" (1977), with its vast ship in lonely interstellar space, and sidesteps Lucas' space opera to tell a story in the genre of traditional "hard" science fiction; with its tough-talking crew members and their mercenary motives, the story would have found a home in John W. Campbell's Astounding Science Fiction during its nuts-and-bolts period in the 1940s. Campbell loved stories in which engineers and scientists, not space jockeys and ray-gun blasters, dealt with outer space in logical ways.

Certainly the character of Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver, would have appealed to readers in the Golden Age of Science Fiction. She has little interest in the romance of finding the alien, and still less in her employer's orders that it be brought back home as a potential weapon. After she sees what it can do, her response to "Special Order 24" ("Return alien lifeform, all other priorities rescinded") is succinct: "How do we kill it?" Her implacable hatred for the alien is the common thread running through all three "Alien" sequels, which have gradually descended in quality but retained their motivating obsession.

One of the great strengths of "Alien" is its pacing. It takes its time. It waits. It allows silences (the majestic opening shots are underscored by Jerry Goldsmith with scarcely audible, far-off metallic chatterings). It suggests the enormity of the crew's discovery by building up to it with small steps: The interception of a signal (is it a warning or an SOS?). The descent to the extraterrestrial surface. The bitching by Brett and Parker, who are concerned only about collecting their shares. The masterstroke of the surface murk through which the crew members move, their helmet lights hardly penetrating the soup. The shadowy outline of the alien ship. The sight of the alien pilot, frozen in his command chair. The enormity of the discovery inside the ship ("It's full of ... leathery eggs ...").

A recent version of this story would have hurtled toward the part where the alien jumps on the crew members. Today's slasher movies, in the sci-fi genre and elsewhere, are all pay-off and no buildup. Consider the wretched remake of the "Texas Chainsaw Massacre," which cheats its audience out of an explanation, an introduction of the chain-saw family, and even a proper ending. It isn't the slashing that we enjoy. It's the waiting for the slashing.

Hitchcock knew this, with his famous example of a bomb under a table. (It goes off -- that's action. It doesn't go off -- that's suspense.) M. Night Shyamalan's "Signs" knew that, and hardly bothered with its aliens at all. And the best scenes in Hawks' "The Thing" involve the empty corridors of the Antarctic station where the Thing might be lurking.

"Alien" uses a tricky device to keep the alien fresh throughout the movie: It evolves the nature and appearance of the creature, so we never know quite what it looks like or what it can do. We assume at first the eggs will produce a humanoid, because that's the form of the petrified pilot on the long-lost alien ship. But of course we don't even know if the pilot is of the same race as his cargo of leathery eggs. Maybe he also considers them as a weapon. The first time we get a good look at the alien, as it bursts from the chest of poor Kane (John Hurt). It is unmistakably phallic in shape, and the critic Tim Dirks mentions its "open, dripping vaginal mouth."

Yes, but later, as we glimpse it during a series of attacks, it no longer assumes this shape at all, but looks octopod, reptilian or arachnoid. And then it uncorks another secret; the fluid dripping from its body is a "universal solvent," and there is a sequence both frightening and delightful as it eats its way through one deck of the ship after another. As the sequels ("Aliens," "Alien 3," "Alien Resurrection") will make all too abundantly clear, the alien is capable of being just about any monster the story requires. Because it doesn't play by any rules of appearance or behavior, it becomes an amorphous menace, haunting the ship with the specter of shape-shifting evil. Ash (Ian Holm), the science officer, calls it a "perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility," and admits: "I admire its purity, its sense of survival; unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality."

Sigourney Weaver, whose career would be linked for years to this strange creature, is of course the only survivor of this original crew, except for the ... cat. The producers must have hoped for a sequel, and by killing everyone except a woman, they cast their lot with a female lead for their series.

Variety noted a few years later that Weaver remained the only actress who could "open" an action movie, and it was a tribute to her versatility that she could play the hard, competent, ruthless Ripley and then double back for so many other kinds of roles. One of the reasons she works so well in the role is that she comes across as smart; the 1979 "Alien" is a much more cerebral movie than its sequels, with the characters (and the audience) genuinely engaged in curiosity about this weirdest of lifeforms.

A peculiarity of the rest of the actors is that none of them were particularly young. Tom Skerritt, the captain, was 46, Hurt was 39 but looked older, Holm was 48, Harry Dean Stanton was 53, Yaphet Kotto was 42, and only Veronica Cartwright at 29 and Weaver at 30 were in the age range of the usual thriller cast. Many recent action pictures have improbably young actors cast as key roles or sidekicks, but by skewing older, "Alien" achieves a certain texture without even making a point of it: These are not adventurers but workers, hired by a company to return 20 million tons of ore to Earth (the vast size of the ship is indicated in a deleted scene, included on the DVD, which takes nearly a minute just to show it passing).

The screenplay by Dan O'Bannon, based on a story he wrote with Ronald Shusett, allows these characters to speak in distinctive voices. Brett and Parker (Kotto and Stanton), who work in the engine room, complain about delays and worry about their cut of the profits. But listen to Ash: "I'm still collating it, actually, but I have confirmed that he's got an outer layer of protein polysaccharides. He has a funny habit of shedding his cells and replacing them with polarized silicon which gives him a prolonged resistance to adverse environmental conditions." And then there is Ripley's direct way of cutting to the bottom line.

The result is a film that absorbs us in a mission before it involves us in an adventure, and that consistently engages the alien with curiosity and logic, instead of simply firing at it. Contrast this movie with a latter-day space opera like "Armageddon," with its average shot a few seconds long and its dialogue reduced to terse statements telegraphing the plot. Much of the credit for "Alien" must go to director Ridley Scott, who had made only one major film before this, the cerebral, elegant "The Duelists" (1977). His next film would be another intelligent, visionary sci-fi epic, "Blade Runner" (1982).

Though his career has included some inexplicable clinkers ("Someone To Watch Over Me,") it has also included "Thelma & Louise," "G.I. Jane," "Gladiator" (unloved by me, but not by audiences), "Black Hawk Down" and "Matchstick Men." These are simultaneously commercial and intelligent projects, made by a director who wants to attract a large audience but doesn't care to insult it.

"Alien" has been called the most influential of modern action pictures, and so it is, although "Halloween" also belongs on the list. Unfortunately, the films it influenced studied its thrills but not its thinking. We have now descended into a bog of Gotcha! movies in which various horrible beings spring on a series of victims, usually teenagers. The ultimate extension of the genre is the Geek Movie, illustrated by the remake of "Texas Chainsaw Massacre," which essentially sets the audience the same test as an old-time carnival geek show: Now that you've paid your money, can you keep your eyes open while we disgust you? A few more ambitious and serious sci-fi films have also followed in the footsteps of "Alien," notably the well-made "Aliens" (1986) and "Dark City" (1998). But the original still vibrates with a dark and frightening intensity.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

117 minutes