Now streaming on:

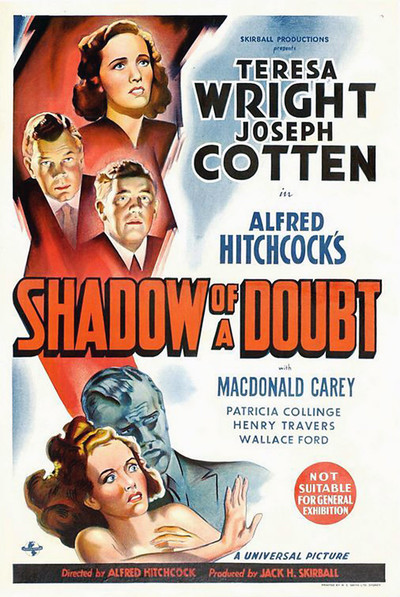

No one would ever accuse Alfred Hitchcock's "Shadow of a

Doubt" of being plausible, but it is framed so distinctively in the

Hitchcock style that it plays firmly and never breaks out of the story. Later

you question the absurdity of two detectives following a suspect from New York

to California, apparently without being sure of how he looks, and hanging

around idly outside his residence for weeks while chatting up the suspect's

niece; one of them eventually even proposes marriage. Nor are we convinced that

the niece, believing her uncle is a killer of old ladies, would allow him to

buy her silence by promising to leave town (because his guilt would "destroy

her mother").

One of Hitchcock's favorite subjects was The Innocent Man Wrongly Accused. In "Shadow of a Doubt," there's no possibility of innocence. It's clear from the outset that Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) is the notorious "Merry Widow Killer," and more than once Hitchcock cuts to nightmarish fantasies of (presumably) merry widows waltzing. We first see Charlie lying on top of his bed, smoking a cigar, when told by his landlady two men had been asking for him. He sees them standing on the corner downstairs, packs a bag with cash, leaves the house and boldly walks right past them. This demonstrates they don't know what he looks like, but not why they wouldn't be interested inanyman leaving the boarding house. The incompetence, and apparently unlimited expense account, of these two cops is one reason the action can span several weeks.

Charlie's peppy niece Charlotte (Teresa Wright), nicknamed "Young Charlie" after her uncle, has idolized him for years, and complains to her family that life wouldn't be so dull if he paid them a visit. Amazingly, that day they receive a telegram telling them to expect him. In a well-known shot Hitchcock shows Charlie's train arriving beneath an ominous cloud of black smoke. He has arrived in Santa Rosa, California, a paragon of small towns that could have modeled for Norman Rockwell'sSaturday Evening Postcovers.

The town and the Newton family play major roles in the film, and may reveal Hitchcock's own inner feelings. He shot in late 1941 and early1942, at the outset of World War II, at a time when he was unable to visit his dying mother in London because of wartime restrictions. He later credited the friendliness of the town for making this the most pleasant of all his film locations. His emphasis on the comfy Newton home, a chatty neighborhood, a corner cop who knows everyone's name, the nightly meals around a big dining table--all add up to a security that both he and Uncle Charlie were seeking, and Charlie rhapsodizes about the joys of home and family. The visiting uncle is so quickly embraced by the town there is even a ceremony in his honor.

What we begin with, then, is the innocent Newton family and the sinister uncle, who moves into Young Charlie's room at the top of the stairs. Also in the family are her father Joseph (Henry Travers), her mother Emma (Patricia Collinge), and her young sister Ann (Edna May Wonacott) and brother Roger (Charles Bates). Travers was in his late 60s and Collinge around 50 when the film was made, and they look on the old side for Ann and Roger's parents but about right for the movie's apple pie symbolism. The next door neighbor, who drops in without knocking, is Herb (Hume Cronyn, in his movie debut). He and Joseph are crime buffs and spend much time in debates about methods of committing a perfect murder. Their asides are funny in themselves, and more so because of Uncle Charlie's discomfiture. His preferred method is strangulation with his bare hands.

So now everyone is onstage. The uncle, the family, the neighbor, the cops (notably the good-looking younger detective Jack, played by Macdonald Carey, who falls in love with Young Charlie). With Uncle Charlie seemingly content to spend the rest of his life in Santa Rosa, Hitchcock needed something to create a shadow of a doubt, and I suppose his MacGuffin this time is a story in the newspaper about the Merry Widow Killer. This story might have passed unnoticed if Uncle Charlie didn't unwisely and unsuccessfully try to conceal it. That triggers Young Charlie's growing suspicion that there must be more to her uncle than it appears. Charlie has a dark side to his nature, a way of narrowing his eyes and seeming threatening, that is later, somewhat awkwardly, accounted for by a head injury when he was young.

The engine of the plot then involves Young Charlie's suspicion and her uncle's paranoia and clumsy attempts to murder her--as if that would accomplish anything more than confirming the suspicions of Jack the cop. As plots go, this one is not a Hitchcock masterpiece, but it works because it generates suspense; how close to the truth will the niece come before she's killed or proven right? During the running length of the film the elements all mesh efficiently; it's later that the weaknesses grow evident.

Much of the film's effect comes from its visuals. Hitchcock was a master of the classical Hollywood compositional style. It is possible to recognize one of his films after a minute or so entirely because of the camera placement. He used well-known camera language just a little more elegantly. See here how he zooms slowly into faces to show dawning recognition or fear. Watch him use tilt shots to show us things that are not as they should be. He uses contrasting lighted and shadowed areas within the frame to make moral statements, sometimes in anticipation before they are indicated. I found while teaching several of his films with the shot-by-shot stop-action technique, that not a single shot violates compositional theory.

Not many directors were fonder of staircases than Sir Alfred. They impose a hierarchy of power and weakness. A character at the top of the stairs can seem to loom or be in danger of toppling, depending on whether the POV is high and low. The flow at the house goes up the sidewalk, onto the porch, through the door and directly up the stairs. There are outside stairs in the back, and both staircases are used for tight little sequences of threat and escape. Notice how many variations of camera angles and lighting Hitchcock uses with the stairs. He considered them an ideal device for introducing imbalance into otherwise horizontal interiors. So important were they to him, so memorably used, that I can name some of his titles and if you've seen them you will instantly recall the stairs: "Notorious," "Psycho," "Strangers on a Train," "Frenzy" and of course "Vertigo."

Joseph Cotten and Teresa Wright do all the heavy lifting in the acting department. The other characters are bundles of clichés. One of Hitchcock's inspirations for the film was Thornton Wilder's "Our Town," inflaming his yearning for domesticity at a time when Britain was already at war. In a way there are two movies here: A Hitchcock, and a nostalgic small town fantasy. So innocent is the town that Uncle Charlie walks into the bank where Joseph Newton is president, deposits tens of thousands of dollars in bills from his briefcase, and Joseph never asks a question. The Newtons aren't given much to suspicion. The two detectives at one point cook up a harebrained story that they're working on a national survey that requires them to photograph the rooms Americans live in. Of course they hope to begin with the Newton residence, and Uncle Charlie's room. The front and back stairs come much into use here. How many bankers' families would believe that story?

Cotten has one of the best scenes of his career, in a dinner tale conversation. His dark side takes over, and he finds himself saying these extraordinary words: "The cities are full of women, middle-aged widows, husbands dead, husbands who've spent their lives making fortunes, working and working. And then they die and leave their money to their wives, their silly wives. And what do the wives do, these useless women? You see them in the hotels, the best hotels, every day by the thousands. Drinking the money, eating the money, losing the money at bridge. Playing all day and all night. Smelling of money. Proud of their jewelry but of nothing else. Horrible, faded, fat, greedy women... Are they human or are they fat, wheezing animals, hmm? And what happens to animals when they get too fat and too old?" I think that may be the most eloquence Hitchcock ever allowed a killer.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

108 minutes

Hume Cronyn as Herbie Hawkins

Henry Travers as Joseph Newton

Macdonald Carey as Jack Graham

Joseph Cotten as Uncle Charlie Oakley

Patricia Collinge as Emma Spencer Oakley Newton