Now streaming on:

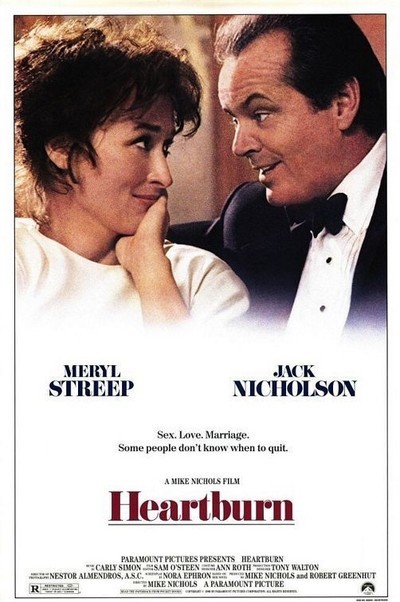

Maybe Nora Ephron should have based her story on somebody else's marriage. That way, she could have provided the distance and perspective that good comedy needs. Instead, she based "Heartburn" - first her novel and now her screenplay - on her own marriage. And she apparently had too much anger to transform the facts into entertaining fiction. This is a bitter, sour movie about two people who are only marginally interesting.

The characters are Rachel, a New York writer, and Mark, a Washington political columnist. The originals for the characters are Ephron and Watergate journalist Carl Bernstein, whom she married and then divorced when she learned he was having affairs.

In the movie, the characters are played by Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson, and just by seeing their names on the marquee you'd figure the movie would have to be electrifying. But it's not. Here is the story of two people with no chemistry, played by two actors with great chemistry. The only way they can get into character is to play against the very things we like them for.

Streep seems dowdy and querulous. Nicholson seems to be a shallow creep. Their romance never really seems real, never seems important and permanent. So when he starts fooling around, we don't feel the enormity of the offense. There's not much in their marriage for him to betray.

The story: Rachel meets Mark and it's love at first sight, but it's not the kind of loin-churning passion we felt when Nicholson met Kathleen Turner in "Prizzi's Honor." It's more of a low-grade fever, something to be treated with aspirin - or marriage.

On her wedding day, Rachel takes to the bedroom of her father's apartment and refuses to emerge for hours. Her reluctance is touching at first, then comic and finally annoying. After the ceremony, they move into a handyman special in Georgetown (affordable because it recently had a fire), and the joke is that the renovations to the house will last longer than their marriage.

There are scenes set in the thickets of Washington gossip, where Catherine O'Hara plays the reigning bitch goddess, and other scenes of domesticity, as when Nicholson wonders why the carpenters have not supplied a doorway from the kitchen to the rest of the house.

Here and there, we see glimmers of the greatness of both Nicholson and Streep, who on an ordinary day with a decent script can act circles around anybody. There's a scene in a maternity ward where Streep comes out of anesthesia and turns to see Nicholson standing there holding their baby. She asks if it's theirs, and the goofy grin on his face is a moment of pure joy.

There's another moment where they sing nursery songs to each other. And a moment when Nicholson sits by her bed and cries, because he knows that the flaws in his character will make it impossible for him to function responsibly as a husband and father.

Those moments are adrift in a sea of ennui. "Heartburn" is punctuated by scenes that feel like the director, Mike Nichols, is marking time. Was Bernstein's dislike for the project so great that the filmmakers prudently left out all of the really good stuff? If I were Bernstein, I would rather beportrayed as a colorful rake than as the hapless fall guy in this movie. If they're going to remember you at all, it's not going to be for being unmemorable.

"Heartburn" not only misses in its treatment of the two central characters, it also fails to give us a real sense of the New York-Washington media axis. The O'Hara character comes closest; I guess she's supposed to be a cross between celebrity reporter Barbara Howar and Washington gossip columnist Diana McClellan. She puts the right spin on her sly reports of the latest transgressions and infidelities.

But Nicholson never seems to be a Washington columnist. Most of the time, he doesn't have much to say. The Streep character is supposed to be some kind of a food writer, but what we totally miss is the manic desperation of the typical New York free-lancer. She seems too placid and laid back. She ought to be pitching projects and trying to get big advances.

When she wrote the screenplay, Ephron missed a bet by not writing in some scenes in which her character meets with a New York publisher and tries to pitch a comic novel in which she rips the lid off of her marriage to a famous journalist. If we're going to base a story on a real marriage, let's go all the way.

After we've eviscerated the philandering husband, why stop before we get to the part where the ex-wife violates her own privacy and that of her children in a bid for revenge, the best-seller list and a sale to the movies? And what about the ex-husband's offer to sue? I had the strangest feeling that "Heartburn" ended just when it was starting to get interesting.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

110 minutes

Richard Masur as Arthur

Jack Nicholson as Mark

Maureen Stapleton as Vera

Stockard Channing as Julie

Jeff Daniels as Richard

Meryl Streep as Rachel

Catherine O'Hara as Betty