Now streaming on:

“Moffie” is one of those films where you’ll get more out of it if you bring a specific nostalgia for, or firsthand cultural experience of, what takes place in its story. Director Oliver Hermanus employs the technique of purposely leaving all emotion out of the film, opting instead to attempt an evocation of Stanley Kubrick in feeling and Terrence Malick in visuals. Cinematographer Jamie Ramsay provides some strikingly pretty pictures, but Hermanus makes the mistake of thinking Kubrick was a cold and unfeeling director. This common assumption is not true; viewers feel for Wendy and Danny, for HAL and for Vincent D’Onofrio’s Private Pyle, the tragic figure of “Full Metal Jacket.”

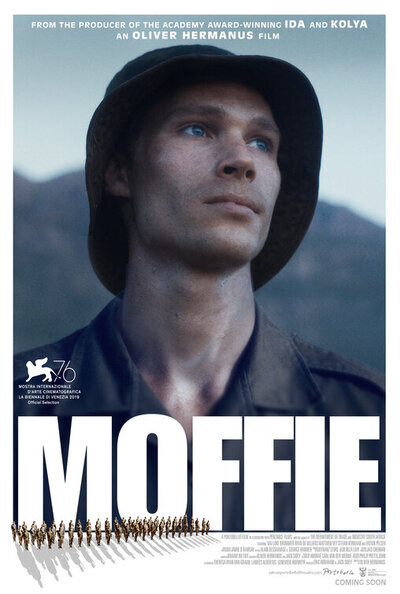

I bring up Kubrick’s 1987 Vietnam drama because much of “Moffie” takes place in a brutal boot camp specifically designed to turn teenagers into heartless killing machines. The recruits are tormented by Sergeant Brand (Hilton Pelser), who is just as brutal as R. Lee Ermey’s drill sergeant though far less interesting. Most of his dialogue consists of screaming out the N-word and the homophobic slur the subtitles translate whenever the film’s title is uttered. Unlike “Full Metal Jacket,” however, these grunts are virtually indistinguishable outside of our protagonist, Nicholas van der Swart (Kai Luke Brummer). When one frazzled recruit suddenly blows his own head off with his rifle, I questioned whether I’d met this character before. Nicholas looks on with a dazed, emotionless expression on his face, which is how he spends about 90 percent of this film. He is such a symbolic, one-dimensional drone that even the rare tender moment fails to evoke much of a response on his part.

Sixteen-year-old Nicholas enlists in 1981 to serve the two years of military conscription required for all White men. We are told of this requirement in the opening titles, but the press release explains why it is necessary: “the threat of communism and ‘die swart gevaar’ (the so-called black danger) is at an all-time high. But that’s not the only danger Nicholas faces.” I wish I had read this release before watching the film, as it would have given me the foresight that this movie had no intention of speaking to a viewer like me. I may have been able to better calibrate my expectation. When the press release implies that the oppressed minority is a danger to its oppressor protagonist, it’s clear that the film aims to speak to, and identify with, the oppressor.

This is an intriguing path to follow, as Hermanus is a Black director casting his film in an explicitly White gaze. The two times Black characters appear, they are either being racially abused by the adolescent recruits or killed by Nicholas. Their suffering is the sole characteristic of their humanity. That first scene implies that “Moffie” will interrogate apartheid in some fashion, but it does not, leaving me to wonder why that scene exists if the film intends to show the military’s role in fomenting hatred; these kids have already learned it at home. The latter scene occurs once the film pivots to war movie mode, showing the fruits of the military training’s labor. I was more interested in asking the director about his choices than watching them play out, reminding me of Gene Siskel’s question about whether a documentary about the film would be more interesting than the film itself.

But I digress. As “Moffie” opens, Nicholas’ family is celebrating the night before his leave. He is given a girlie magazine as a going away present, a symbolic gesture because he’s about to be trained in the South African ideal of a straight White man who thinks Blacks are inferior. It’s also a useless gesture, as Nicholas is desperately hiding his homosexuality. The other gents at this party wax nostalgic about their fraternal experience, a nostalgia that would stick in the craw of a film unafraid of offending its core audience. Everybody has to endure this government-mandated hazing, and if you survive, you’re truly a man’s man.

That other danger alluded to in the press release I cited is “Ward 22,” an asylum for those who even remotely convey a thought or characteristic that can be deemed homoerotic, or are either caught or accused of being in flagrante delicto with another recruit. We also hear of the brutal beatings that befall anyone who exhibits gayness, real or imagined. Hermanus is quite successful at showing the irony present in the inherent homoeroticism of training exercises, impromptu Fight Club-style brawls and group showers—the lingering camera gives off a “Military Twinks for Apartheid” vibe—but it barely registers as a proper juxtaposition to Nicholas’ muted attraction to another recruit, Stassen (Ryan de Villiers).

I was frustrated by the way the film pussyfoots around their brief, tender and ultimately unresolved arc, though Hermanus tries to justify this by giving us a flashback to Nicholas’ youth. This is the only peek into the character’s psyche that we get, and it proves that Nicholas deserved to be more fleshed out than he is. The scene shows just how deeply ingrained homophobia is in the culture, as a very young Nicholas is dragged out of a locker room by a grown man who has accused him of ogling another boy in the shower. Its harrowing power is almost destroyed, however, because the entire scene is scored to a mopey cover of Seals and Crofts’ “Summer Breeze.” Needle drops like this are the bane of my critical existence.

“Moffie” is based on a beloved autobiographical South African novel by André Carl van der Merwe. I have not read the book, but based on the adaptation, I assume there is a lot of internal monologue about its main character, things that cannot be translated properly into film. The movie was a hit in South Africa before the pandemic struck, leading me to believe that it had what its audience craved. But a film with this incendiary of a title needed to have more to say about being LGBT in a hostile environment. Dick Gregory named his autobiography after the N-word because he said that whenever someone uttered the slur, “they are advertising my book.” Perhaps that’s a common thread with van der Merwe. I can relate to the titles of both of these works, but my sexuality and my Blackness are a package deal. “Moffie” asks me to set one aside, to identify with someone who shares my affection but would hate me otherwise, then does everything in its power to be an unsatisfying punishment for my attempt. Quite frankly, I resented that. Your mileage may vary.

Now playing at the IFC Center and available on demand.

Odie "Odienator" Henderson has spent over 33 years working in Information Technology. He runs the blogs Big Media Vandalism and Tales of Odienary Madness. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here.

104 minutes

Kai Luke Brummer as Nicholas Van der Swart

Ryan de Villiers as Dylan Stassen

Matthew Vey as Michael Sachs

Hilton Pelser as Sergeant Brand

Wynand Ferreira as Snyman

Jan Combrink as Jan Gould

Stefan Vermaak as Oscar Fourie

Hendrik Nieuwoudt as Roos