Now streaming on:

Depictions of trans masculinity in media remain scarce. It’s evident that there’s much to be done for visibility and, more imperatively, to protect the rights and freedoms of trans people at large.

Co-directors Aisling Chin-Yee and Chase Joynt exalt the professional and personal life of jazz musician Billy Tipton in “No Ordinary Man,” and avoid simplification of the trans masculine experience. The documentary relies on Tipton's extraordinary legacy to dissect a wide-ranging list of themes pertaining to the harmful narratives around trans lives.

Assigned female at birth, Tipton assumed a male identity not solely as a vehicle to achieve his artistic ambitions but to carry out every facet of his life. Tipton married, adopted three children, and spent many years as a devoted family man. Upon his death in 1989, however, he was grossly outed by the media and his authentic existence was painted as one of deceit.

His widow, Kathleen “Kitty” Tipton, and eldest son were left to defend the fact that they didn’t know the details of Tipton’s physiology on talk shows that misgendered their loved one. The scrutiny demanded specifics of her intimacy with Tipton and questioned whether his fathering was insufficient for not being a cisgender male. Branded as liars, with their mourning process unfolding under a public microscope, a final blow was issued with the publication of Diane Middlebrook’s opportunistic book Suits Me: The Double Life of Billy Tipton.

Playing it safe in terms of the format but intentional in inviting voices with substance, Chin-Yee and Joynt enlist well-versed speakers such as artist Zackary Drucker, writer Amos Mac (also credited as a writer in the project), and authors Thomas Page McBee and Susan Stryker to comment on Tipton’s transition from famed musical act to private husband and dad, and ultimately to bastion of courage.

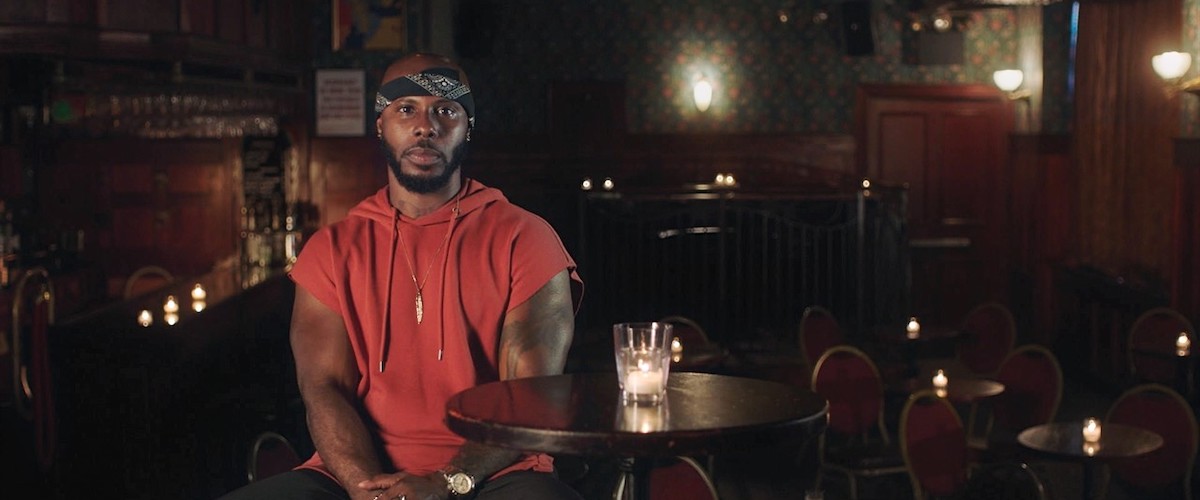

The interviews here are commonplace in execution—individuals sit in empty areas of a nightclub in alluding to Tipton’s work—but they veer between the personal and broader topics around trans identity and gender. The vast majority of those on screen are trans people getting the opportunity to assess the issues facing them on their own terms and not in reference to the cis establishment.

Crucial also to the documentary’s intent is the acknowledgement of the historical presence of trans people in all areas of society, as a way to regain a sense of belonging so long denied to this community. To learn that there were pioneers like Tipton living as their true selves, when their truth was not validated at all, forges a sort of lineage reminding trans folk that their contributions are longstanding. It becomes the movie’s most potent argument.

As an avant-garde device, the filmmakers pepper the conventional sections of conversation and historical information with a series of auditions where trans actors read lines as if playing Tipton. The intent is at least intriguing, even if confusing. To further complicate our limited understanding of this choice, at the some point one of the men and writer Amos Mac share a moment during an audition about a different connection they have that’s never explained.

Still, some of those “behind-the-scenes” moments offer the most touching statements about what Tipton means to the many who follow his steps towards self-actualization. When Marquise Vilson, a Black trans man, partakes in the auditions to play Tipton providing a unique, and more inclusive reframing. His interpretation of some of the musician’s early moments channel his own interactions with a world that still lacks acceptance.

Even without being clear on its purpose, the idea is compelling because trans people are often not offered the same chances to get cast, and it is a rebuttal to the erroneous notion that their identity is performance and not who they really are. One moment, played out by several of the actors in the room, implies that Tipton came into contact with another trans man in the jazz scene. Knowing Tipton met someone in similar circumstance illuminates the faces of the trans men in the present with the joy of recognition. He wasn’t alone.

Other topics discussed at length include the concept of “passing,” which means others perceive you as cisgender, and the difficulty for trans men and women to access health services stand out for their psychological and life-threatening graveness. As the conversation shifts to how significant Tipton’s quiet defiance to be totally himself has been for younger trans men, his son, Billy Tipton Jr., benefits spiritually from seeing his father in a new light. Once a posthumous outcast, Tipton Senior is now a heroic figure. Such realignment of the past is what makes Chin-Yee and Joynt’s doc so refreshing even if visually and structurally standard. They use traditional modes of storytelling to handle revolutionary content. Their points, nonetheless, transcend.

Now playing in theaters.

Originally from Mexico City, Carlos Aguilar was chosen as one of 6 young film critics to partake in the first Roger Ebert Fellowship organized by RogerEbert.com, the Sundance Institute and Indiewire in 2014.

80 minutes

Billy Tipton as Self

Susan Stryker as Self

Kate Bornstein as Self

Zackary Drucker as Self

Amos Mac as Self

Marquise Vilson as Self