When Robert Warshow wrote his directive concerning film criticism, he put it, as many writers reflexively did in the 1940s, as an observation concerning males: “A man watches a movie, and the critic must acknowledge that he is that man.” You can switch genders, or make the statement gender neutral, and the observation, and the directive, still hold. That said, social norms and conventions being what they are, when the person watching the movie is a woman, the critic’s acknowledgement that she is that woman is crucial.

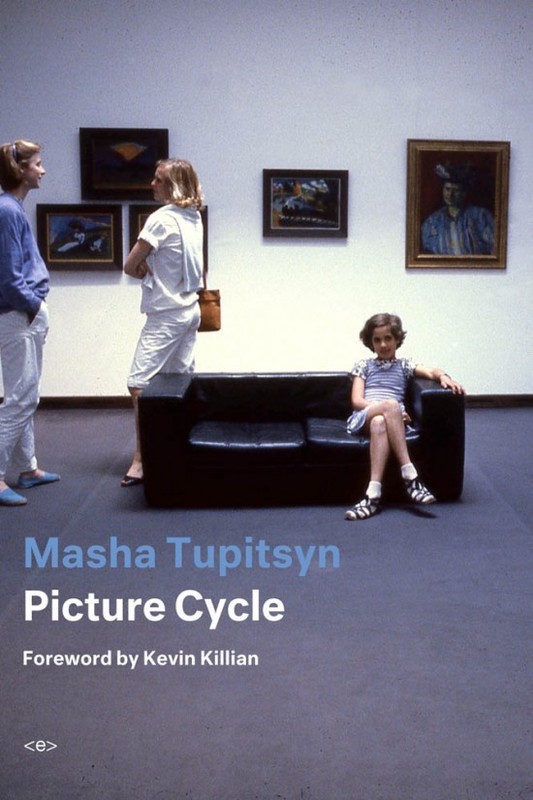

Picture Cycle, a recent book by the critic and multimedia artist Masha Tupitsyn, encompasses both sharp analysis and detailed accounts of what Warshow would call her direct experiences of film. Which are conveyed, purposefully, as the direct experiences of a woman.

In this respect they offer sometimes startling perspectives. As for example her essay A Sentimental Education, which examines the character/performer/real-life-figure male dynamic in “All the President’s Men” and throws in Nora Ephron’s novelistic and on-screen a clef tales of Carl Bernstein for good measure. Late in the essay Tupitsyn states: “In almost every shot of ‘All the President’s Men,’ Bernstein and Woodward are always Two. In the duo of Redford and Hoffman as mise en scène, the two actors remembered each other’s lines and finished each other’s sentences. All four men—the two onscreen and the two offscreen—exemplify a cultural and emotional inside-ness (trust; Two) that only men have been allowed to have with one another when it comes to the dialogue between public and private. In film, history is made up of men who make history together.”

These observations might be immediately possibly slightly infuriating to a fan of the movie, who can protest that the picture tries to actually chronicle an Important Historical Event That Actually Happened. And yet, why does that exempt it. I sometimes teach the movie, and it’s great and imminently teachable, but I always think “aiiieee” at Redford/Woodward’s dismissiveness to the female assistant who actually finds the picture of Ken Dahlberg that sets off the call that breaks open Woodward/Bernstein’s story.

The book alternates—the more accurate term with respect to the direct reading experience would have to be “flows”—between formal critical essays, epigrammatical, notebook-style collections of observations, and personal reminiscences. Even when discussing topics such as relationships dissolving, there’s a through line to art, its production or its consumption. There’s not much in the way of what you’d call “TMI.”

While I’m generally wary of the aforementioned notebook mode, Tupitsyn’s got a beguiling way with it, as seen in this passage from “Time For Nothing:”

“Pier Paolo Pasolini, who put the past on the screen to look at the present, the future in the past, said the world changed in the ‘70s. That it stopped being The World and became something else. Something unknowable. A needle in a haystack. Something you won’t ever find again. No matter how hard you look. Especially if you’re looking hard.

“Pasolini used the past to look at what that something else had been. That something that has no start and no stop and no finish. Derrida said: ‘What is happening is happening to age itself…What is coming…is happening to time but it does not happen in time.’

“What is time now but a perfect body double?”

Like most of us, the author is not immune to some traps the critical mode can lay out. When Tupitsyn passes judgment on Winona Ryder for being too “bougie” to hang in Tribeca in the early ‘90s, her snotty mode of a presumptive omniscience—one that’s all too common in critiques of celebrity culture—is kind of disappointing, not least because of its lack of rigor.

By the same token, though, her reflections of John Cusack as both an actor and a generational icon, in the essay All an Act, are unimprovable and more thought-provoking than anything else ever written about the actor. Picture Cycle is a relatively slim volume, but it has both a density and a suppleness that makes it a book one can return to again and again for bracing insights and new ideas that can compel you to look at familiar things differently.

To order your copy of Masha Tupitsyn's Picture Cycle, click here

Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. He has written for a host of other publications and resides in Brooklyn. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here.