Now streaming on:

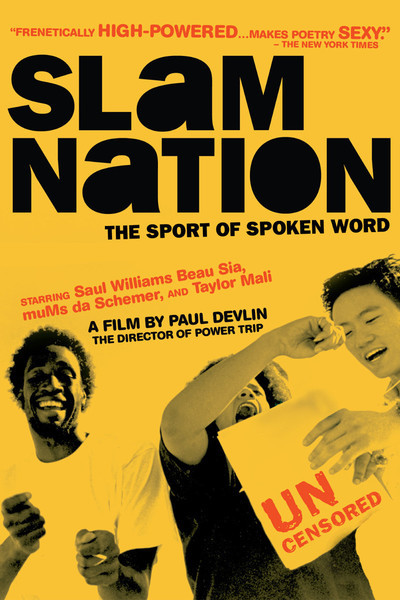

Paul Devlin's "SlamNation" is a documentary about the 1996 National Poetry Slam, held in Portland, Ore., with 27 teams in the competition. The rules are simple: Four members to a team, every member must be a writer as well as a performer, no music, no props, no animal acts. There is a penalty for any poem that goes longer than three minutes. The judges are chosen from the audience. The performers are mostly dressed as if they're about to fix a leak in the basement.

Slams are nothing if not democratic. They are the only sport I'm aware of where the teams from Berwyn and San Francisco compete on the same field. (In 1996, Berwyn actually placed in the final four, led by its star, a slammer named Daniel Ferri, whose poem fiercely defends his baldness.) The documentary follows the New York team, which fielded four first-timers, including Saul Williams, who also stars in the fiction film "Slam," and Mums the Schemer, who plays the character Poet on the HBO prison drama "Oz." In evaluating the poetic content of the slams, one is tempted to take easy shots. (Poetry slams are to poetry as military music is to music?) Most of the material exists halfway between rap music and Vachel Lindsay. Slams are essentially performance art, not literary art, and there is a shot of a New York book editor, sighing at his stack of slam manuscripts and observing that sometimes the poems don't translate well to the printed page.

Maybe that's because "SlamNation," covering three semifinal rounds and the finals, inevitably focuses on the competition rather than the work. I have had one personal experience of slam-style poetry, and it was truly unforgettable.

Last April, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Washington, D.C., the luncheon speaker was Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who rattled off her speech as quickly as she could and hurried from the dais. Then the society's chairman called on a young woman to "give us one of your poems." This was Patricia Smith, a friend of mine from her Chicago days, then a columnist for the Boston Globe. She performed a poem about a visit to a grade school class at which she asked, "How many of you know some dead people?" Almost every hand went up, she said, because all of these inner-city children knew dead people--many of them dead from drugs and gunshots. At the end a little girl thanked her for saying it was all right to know dead people. The girl was speaking of her own murdered mother.

This summary fails to capture the impact of Smith's poem, which surprised me to tears. I looked around the room and thought I had rarely seen so few words have such a strong impact.

Pat Smith of course was soon to get publicity of a different sort, when her paper accepted her resignation after she confirmed that some details of her columns had been made up. Making things up is not what a journalist is supposed to do, but it is what a poet is supposed to do. Seeing Smith again in "SlamNation," as a member of the Boston team, I was reminded of the power of her words. She can see life and touch readers as few writers can. That is her vocation. Fiction and poetry exist to reach a different kind of truth. Maybe she had no business dealing with facts in the first place.

As for the other performers, I am prepared to believe that in context, uncut, seen as they should be, some of them have the same power. Others are basically soapbox orators with a new forum. In the cheerful anarchy of poetry slams, there is room for many styles. As a slammer named Jack McCarthy from Boston says, "You have to write one poem that everyone agrees is a poem. That qualifies you for your poetic license. After that, if you say it's a poem, it's a poem."

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

91 minutes