Now streaming on:

Superstardom privileges some with a lifestyle so ostentatious it removes them from reality. But these beneficiaries also have a digital megaphone that holds more power than that of world leaders, with millions of admirers hanging on every word, demanding entertainers take a stand on matters of social justice or global catastrophe. Meanwhile the public must still wait for the tell-all interviews or emotionally charged documentaries to access a glimpse of the stars’ private lives. Recent examples featured Taylor Swift, Demi Lovato, or Billie Eilish bearing their crippling insecurities and reckoning with the vices of fame.

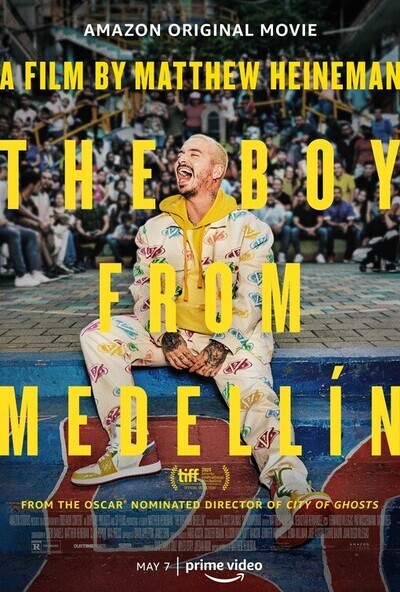

In the engaging and spirited “The Boy from Medellín,” director Matthew Heineman (“Cartel Land,” “City of Ghosts”) frames all these variables in relation to reggaeton maverick J. Balvin over the course of a week in 2019, leading up to his first stadium concert in his hometown just as student protests collapse Colombia.

With Heineman at the helm, the stakes portrayed don’t only mind the concert itself but the gray space between the responsibilities of J. Balvin—to speak out in support of young people fighting for change—and the vulnerability of the man underneath the colorful attires and bold demeanor, José Álvaro Osorio Balvín. Medellín’s most beloved son experiences a turbulent homecoming that moves him to reconsider his stance and the scale of his impact.

Outcries over educational opportunities and access to health services have turned into increasingly violent confrontations between the citizenry and government forces resulting in several deaths in Colombia. As criticism mounts in the press and on social media, Balvín questions whether he should make a statement or remain silent.

Through songs of celebration, his goal is to sell dreams and inspire without an agenda other than his upbeat rhythms and catchy lyrics. But as Taylor Swift recognized in her own documentary shot during the Trump era ("Miss Americana"), being completely apolitical breeds a negative perception. Balvín cares, but admits that his knowledge on the details is limited. Furthermore, he knows that no response will satisfy everyone watching.

Heineman capitalizes on his access by relying mostly on insight provided through exchanges between Balvín and those around him. The performer addresses the camera directly when discussing the timeline from his days as an immigrant painting houses in Miami to honing his skills performing wherever they had him in the early 2000s. Balvín’s numerous hits underscore the piece, while performance sequences that provide more of a concert movie feel bookend it.

There’s no escaping the opulence that surrounds a man who’s topped the charts, collected a slew of awards, and collaborated with the likes of Beyoncé. But while these signs of extreme wealth are present visually throughout, the atmosphere comes off as unpretentious. Balvín suffers from anxiety and depression; meditation and medication have offered salvation. His openness about this invisible struggle, surely maximized by the spotlight, makes him relatable.

Considering that reggaeton was exported from Puerto Rico to the rest of the Americas, the doc could have benefitted from a slightly broader look into its history in the South American country, and Balvín’s position within this incredibly popular and rapidly transforming genre. Colombia is currently a major hub for reggaeton, home to some of the most successful artists in this musical style

Less conspicuous is the realization of the number of people who sustain all aspects of Balvín’s life so that he can eventually get on stages at venues across the globe: from the administrative to his health and his emotional support system. It takes a village.

During the high stress week, with his vocal cords acting up and Colombians demanding a pronouncement, there are visits from his spiritual advisor, his psychiatrist, and his physician; plus interactions with his assistant, his girlfriend, his longtime friends, and other peripheral individuals whose roles aren’t explicitly explained. All feel essential to him.

Through Balvín’s plights, Heineman invites us to consider how entertainers have become commodified and disassociated from their humanity in our eyes. That’s not a cry for pity or compassion, but to investigate our expectations of them as people and not solely as distant figures.

Do we sometimes demand more from those paid to offer distraction than from elected officials? Probably. Have we conflated their large platforms with a duty to offer solutions or enact change? That seems to be the case. And though asking those in those positions to use their power for good is not unreasonable, the pressure of mass opinions tends to get out of hand.

“The Boy from Medellín” confronts José Álvaro Osorio Balvín with J. Balvin at a critical moment in his career, and more significantly for his homeland’s futures. At the core of these conjectures is his favorite song, “El Cantante” by Puerto Rican singer Héctor Lavoe, who got a biopic a few years ago. The lyrics speak of a singer’s obligation to amuse while in front of a paying audience, to forget about his own tribulations, and project what the world wants to see. On stage, the crowd’s screams showers him in glory, but the deceptive glow vanishes when he steps off it.

Now available on Amazon.

Originally from Mexico City, Carlos Aguilar was chosen as one of 6 young film critics to partake in the first Roger Ebert Fellowship organized by RogerEbert.com, the Sundance Institute and Indiewire in 2014.

95 minutes