Now streaming on:

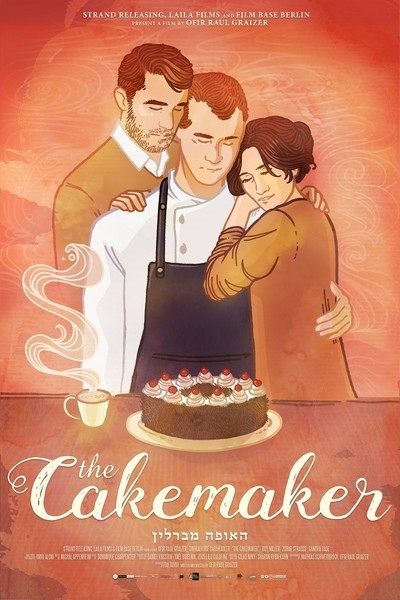

Thinking back on “The Cakemaker,” a terrifically impressive feature debut by Israeli writer/director Ofir Raul Graizer, I began pondering the difference between films that actually derive from novels and those which seem like they do but don’t. Graizer’s film, about a young German guy drawn to the Israeli family of his deceased male lover, belongs to the latter category. Watching it, the film’s intelligent, well-crafted story and beautifully drawn characters seem to suggest literary roots. But examine those virtues more closely and it becomes evident that here they’re owed to a form of storytelling that’s essentially cinematic, one that depends on a quality that distinguishes this film throughout: its extraordinary delicacy and restraint.

In some ways, “The Cakemaker” reminded me of filmmakers such as Claude Sautet. But if the French pioneered and perfected a form of carefully nuanced, slightly melancholy emotional naturalism, that cinematic species now belongs to the international art film, and proves its worth again in this film’s conjunction of Israeli and German cultures, with all the non-romantic associations such a convergence implies.

The story begins in a small, tidy German café/bakery. Oren (Roy Miller), a bearded Israeli transportation engineer who visits Berlin occasionally on business, discusses the displayed cakes and pastries with the helpful young man working behind the counter, Thomas (Tim Kalkhof). Oren wants cinnamon cookies to take home to his family, and soon he also enlists Thomas’ help in a search to find a toy train for his six-year-old son. We never see that shopping expedition. Instead, in a private space, we see a hand put down a glass of wine, and the men kiss.

Cut to several months later. Oren and Thomas are now living together, though the former spends a lot of time in Israel. One day Oren goes away and never returns. When Thomas investigates, he discovers that his lover has been killed in a car accident in Jerusalem.

So Thomas goes there. There is no evident purpose to his trip, but we can infer that perhaps it’s his way of grieving, or seeking solace by learning about the part of Oren’s life that had previously been invisible. As it happens, Oren’s widow Anat (Sarah Adler) owns a café. Thomas goes there, has coffee and asks if he she needs a worker. She says no. But soon after, she realizes she does need help and offers him a part-time job. He never says anything about knowing her late husband and, for a good while, she has no reason to suspect the connection.

Thomas soon reveals his skills at baking, and his flour-butter-sugar creations—which the film photographs with delectable care—quickly become popular additions to the café’s menu. His contribution is not without its complications, however. Unlike Anat, Oren’s brother Motti (Zohar Strauss) is religious and insists that Thomas touching the stove would endanger the shop’s kosher credentials.

The textures of contemporary Israeli life, including the friction between religious and non-religious Jews, are carefully, sensitively registered here, as are the differing ways that Israelis interact with a German in their midst. While there are glances of suspicion and distaste, they’re muted and fleeting. And Anat’s family gradually extends its hospitality to him, with Motti even finding him an apartment and inviting him to Shabbat dinner.

Throughout, the film lets us apply our readings to what it shows us, rather than imposing its own. This is especially true of Thomas. Kalkhof’s remarkable performance is one that seems founded on stillness and silence, which we can imagine are natural defenses for a young man who has been deeply wounded by life. With his alabaster skin and limpid gaze, Kalkhof makes Thomas at once believably present yet mysteriously remote. What motivates him? What finally is he hoping to find or achieve? In the film’s second half, Graizer’s skillfully structured script returns to Oren and Thomas’ relationship and lets us learn things about the younger man’s past that help explain his character and actions.

Commendably, the film treats issues of sexuality and sexual identity as subtly and indirectly as it does other potentially hot-button topics. Here, desire is fluid and multi-faceted, and connected to many other life issues and emotions rather than being a factor explained by reductive labels or assumptions. In this as in other areas, the careful reticence of Graizer’s approach has the welcome effect of drawing the viewer ever more deeply into the story.

That story is finally both convincing and quietly moving, a tale of emotional journeys and trials and the challenge of starting anew after tragedy. The brilliance of its telling marks a very auspicious debut by the talented Graizer.

Godfrey Cheshire is a film critic, journalist and filmmaker based in New York City. He has written for The New York Times, Variety, Film Comment, The Village Voice, Interview, Cineaste and other publications.

104 minutes

Sarah Adler as Anat

Tim Kalkhof as Thomas

Royal Miller as Oren

Zohar Strauss as Moti

Sandra Sade as Hanna