Now streaming on:

Like the Edith Wharton novel that inspired it, Terence Davies' "The House of Mirth" conceals rage beneath measured surface appearances. This is one of the saddest stories ever told about the traps that society sets for women. Perhaps its characters fear that if they ever really spoke their thoughts, their whole house of cards, or mirth, would tumble down. And so they speak in code, and people's lives are disposed of with trivial asides and brittle wit.

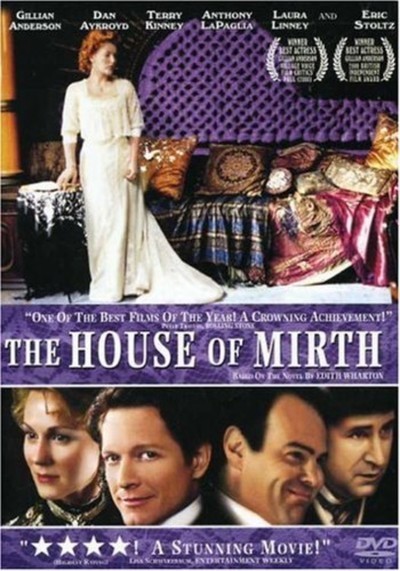

The movie tells the story of Lily Bart (Gillian Anderson), a respectable member of New York society in her late 20s, who keenly feels it is time for her to be married. Is there nothing else she can do? Apparently not; her upbringing has equipped her for no trade except matrimony, and even Lawrence Selden (Eric Stoltz), her would-be beau, observes dispassionately: "Isn't marriage your vocation? Isn't that what you were brought up for?" Lily is alone in the world, except for a rich maiden aunt, from whom she expects an inheritance. She lives in a world of lunches and teas, house parties and opening nights, where she is no longer a fresh face: "I've been about too long. People are getting tired of me." But her life is not unpleasant until a chain of events destroys her with the thoroughness and indifference of a meat grinder.

She goes to tea at Selden's house, and is seen leaving by Mr. Rosedale (Anthony LaPaglia). He knows that only bachelors live in the building. For a woman to go unaccompanied to a man's room is not proof she is a tramp, but might as well be. Rosedale guesses something of Lily's financial situation, and makes her an offer she refuses. So, too, in a different way, does Gus Trenor (Dan Aykroyd), playing one of those rich men who offer investment advice to desirable women as if they have only benevolence on their minds.

Lily's social world includes George and Bertha Dorset (Terry Kinney and Laura Linney). Bertha flaunts her infidelities, and George is too timid, or well-mannered, to rise to the bait. She all but insists Lily accompany them on their yacht in the Mediterranean, and then gets herself out of a tight spot by a subterfuge against Lily so cruel and unfair, it almost rips the fabric of the film. After that, Lily is all but done for, although her descent is gradual.

"Men have minds like moral flypaper," Lily observes. "They will forgive a woman almost anything except the loss of her good name." As Lily finds her credit in society running out, she turns to the resources she has left--or thinks she has--and we see finally that she is defeated. She is prepared for two things in life, to be a rich man's wife or to do piecework at poverty wages. The vise that closes on her in the final scenes is inexorable.

And yet she could have prevented her fate. There is the matter of a debt to Gus Trenor. We modern viewers are thinking that she need not repay it, that he is a louse and she can save herself, but that is not the sort of thing that would occur to Lily. Nor can she accept a liaison of convenience with Rosedale. She cannot keep a job as a rich man's companion because her reputation is wanting. Everyone knows the truth about her--that she is not a bad woman but an admirable one--and yet no one will act on it, because perceptions are more important than reality. What finally defeats Lily Bart is her own lack of imagination, her inability to think outside the envelope she was born within.

Anderson seems an unexpected choice as Lily. Apparently Davies saw a still of her in "The Mighty" (1998) and made her his first choice. Her success on "The X-Files" might seem to disqualify her, but Anderson's talent has many notes, and I liked the presence she brought to Lily Bart. It would be wrong, I think, to cast the role as a fragile flower; Lily is a strong, healthy and competent woman who has everything she needs to lead a long and happy life, except (1) a husband, or (2) a society that provides for independent women.

Edith Wharton, a sharp and unforgiving chronicler of New York society, knew that, and knew that her own independence was based on her self-employment as a novelist. It is ironic that Virginia Woolf, in A Room of One's Own , writes about Jane Austen and other earlier women writers as finding the only profitable and challenging female occupation that could be undertaken in a drawing room, and Wharton was still illustrating that a century later.

Davies' "The House of Mirth" will be compared with Martin Scorsese's "The Age of Innocence," also based on a Wharton novel. The two directors focus on different sides of Wharton's approach. Wharton as a writer was a contemporary of her great friend Henry James, and also of the rising group of realists like Dreiser. The Age of Innocence is a Jamesian novel, but The House of Mirth is more like Dreiser, like an upper-class version of Sister Carrie , in which a woman's life is defined by economic determinism. (If Lily had read Sister Carrie, indeed, it might have given her some notions about how to survive.) The movie will seem slow to some viewers, unless they are alert to the raging emotions, the cruel unfairness and the desperation that are masked by the measured and polite words of the characters.

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

140 minutes

Gillian Anderson as Lily Bart

Laura Linney as Bertha Dorset

Eric Stoltz as Lawrence Selden

Dan Aykroyd as Gus Trenor

Eleanor Bron as Mrs. Peniston

Anthony LaPaglia as Sim Rosedale