Now streaming on:

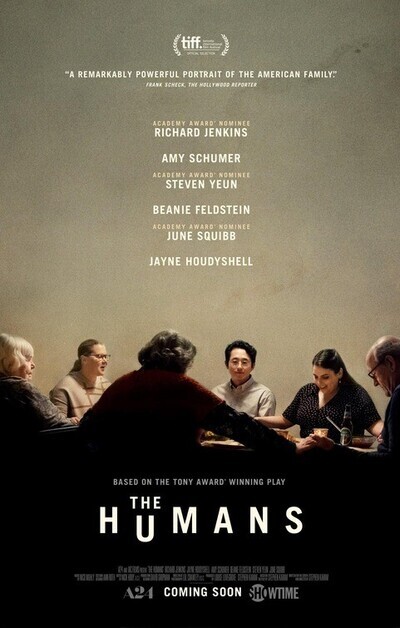

"The Humans" is a film that will make you thankful that not every Thanksgiving dinner is like the one depicted in this movie. Written and directed by Stephen Karam, who adapts his own Tony-winning 2016 Broadway play, the movie is set on Thanksgiving day in the barely-furnished downtown Manhattan apartment of Bridgid Blake (Beanie Feldstein) and her boyfriend Richard (Steven Yeun). As it introduces Brigid's father Erik (Richard Jenkins), mother Deidre (Jayne Houdyshell), sister Aimee (Amy Schumer) and grandmother Momo (June Squibb), "The Humans" follows many of the conventions of the "holiday gathering goes awry" genre, intimating the tensions and schisms in the Blake family rather than spelling them all out right away, and patiently planting seeds of repressed traumas and grudges, secrets and lies that will flower into catharsis in the final act.

Karam drops breadcrumbs to establish the Blake family, using Richard as a easy excuse to deliver exposition, since he's the prospective new member and an outsider in more ways that one (he's Korean-American and seemingly more intellectual and introspective than all of the Blakes save for Brigid). The Blake family hails from Scranton and remains connected to what seems to be a very right-wing Catholic church. Grandma Momo, who is in a wheelchair and suffers from dementia, was a devout and once-formidable congregational fixture. Deidre seems to have absorbed some of her mother's reactionary cultural attitudes even though she does a bad job of pretending to be enlightened. She keeps making remarks about Aimee, a lesbian, that are no less hurtful for being passive-aggressive. She also texts Aimee whenever there's awful news about a lesbian—most recently the story of a daughter of a family friend who died from suicide.

Brigid gets grief over having left the family stomping grounds and resettled in New York for college. There are lingering feelings of rejection in the way the Blake parents interact with Brigid on what ought be her day to be in charge and play party hostess. Both parents ridicule and diminish the apartment, which looks gorgeous and immense to this adoptive New Yorker (though I guess it seems bad if you're a homeowner from Scranton?). Erik jabs at Brigid for having chosen a financially draining private college over a state school, and there's a subtext of white, middle-class discomfort in some of the interactions between Richard and the Blakes, no matter how hard they try to seem accepting. And it's clear from the start that Erik, a former Scranton school janitor, is sitting on a shameful secret.

After the first few minutes, audiences might be forgiven for thinking, "this is a lot like other stories of its type, only slower and artier." But give it time and try to lean into the style. "The Humans" feels strikingly different from other movies in this vein, thanks to the way it's written (elliptically and subtly, dancing around the obvious) and, even more so, the way it's directed. There are no monsters, ghosts or demons, yet every frame feels haunted thanks to how Karam, cinematographer Lol Crawley, and editor Nick Houy unveil and inspect the setting, a pre-World War II, almost lightless "interior courtyard" apartment with scuffed hardwood floors, stained and cracked walls, and a counterintuitive layout.

At times the movie feels like "Hereditary" without the supernatural elements and gore. It's a psychological horror movie about the ordinary miseries and compromises of family. You can feel the tension radiating from all of them, as if they were mortals being watched by ghosts, or (conversely) ghosts being observed by parapsychologists, blobs of energy whose every shift in feeling registers as a change in color temperature.

The filmmakers sometimes park the camera on the far side of the apartment and watch action unfold through the frame-within-a-frame of a doorway 20 feet away, with characters passing in and out of view. Other times they linger over details of design and decay, tracking over bulges in the wall that are probably the result of multiple paint-overs, humidity and steam pipe damage and the like, but that have an H.R. Giger-esque body-horror vibe, as if they're alien egg sacs pregnant and about to burst.

In one of many wordless, remarkable scenes, Brigid's sister Aimee makes one of her frequent trips to the bathroom to anxiously scan her text messages (obviously something dreadful has happened for her personally, but we won't find out what till later) and she turns on the faucet to camouflage the sound of whatever she's about to do in there. The camera drifts downward, tracing the porcelain body of the sink, passing the spot where the base meets the dirty tile, and passes through the floor, revealing the level where the rest of the family is gathered, letting us hear their offscreen voices while we observe how the faucet (leaky, unbeknownst to Aimee) is causing some kind of mucus-like film to drip down the walls in a vein-like pattern.

The movie often presents moments this way, making it seem as if the characters are triggering changes in the architecture, or awakening psychic energies from those who lived here long ago.

This is one of the eeriest family comedies ever made.

In theaters and on Showtime today.

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor at Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.

108 minutes

Richard Jenkins as Erik Blake

Jayne Houdyshell as Deirdre

Steven Yeun as Richard

Beanie Feldstein as Brigid

Amy Schumer as Aimee

June Squibb as Momo