When it was officially announced that David Lynch’s groundbreaking series “Twin Peaks” was returning for a third season a quarter century after its initial premiere, one of the show’s most ardent fans, Scott Ryan, had an immediate desire for there to be coverage of it. He knew that if he wanted it, there likely were others who would as well, so three months prior to the premiere of 2017’s 18-part masterwork, “Twin Peaks: The Return,” Ryan released the first issue of The Blue Rose Magazine. It is a beautifully designed fan publication filled with insightful essays and in-depth interviews that any admirer of Lynch’s work is guaranteed to embrace like a spirit-filled log. A year later, Ryan and David Bushman formed the publishing company Fayetteville Mafia Press, which has released multiple essential books on the work of Lynch, the latest being Ryan’s own Fire Walk With Me: Your Laura Disappeared, a marvelous collection of exclusive articles commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of Lynch’s long misunderstood 1992 film, “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me.”

I purchased my copy of Ryan’s book at last month’s “David Lynch: A Complete Retrospective—The Return,” programmed by Daniel Knox at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, where I met the author and his wife, Jen. What Knox created with the retrospective was as powerful a communal experience and creatively reinvigorating retreat as Ebertfest, the festival founded by Roger Ebert at his alma mater, the University of Illinois. Both Ebert and Knox are gifted at fostering the sort of engaged moviegoing that makes audiences open to immersing themselves in challenging and revelatory cinematic works, and the same could be said of Ryan’s book. This month, I spoke at length with Ryan via Zoom about the therapeutic nature of Lynch’s artistry, the profound impact that Sheryl Lee’s portrayal of Laura Palmer has had on his life and much more.

One thing I love about this scholarly yet playful book is that you can sense the fun you’ve had while writing it.

Honestly, I don’t know how to be any other way. What I’ve been telling people is that I won’t say this is the best “Twin Peaks” book, but I will say it’s the funniest.

The book is also startlingly candid, going so far as to include the revelation that you stole a copy of the “Fire Walk With Me” VHS when it was released, due to its formidable price. Are there people you’ve looked up to who can be simultaneously witty and sincere, such as the titular subject of your book, The Last Days of Letterman?

I’m certainly a product of David Letterman. I watched every episode of his CBS show, though I can’t say that I saw his entire NBC show because I was 11 or 12 when it started. But once I discovered it in high school, Letterman became my beacon in life. Dave could give a 9/11 speech that would make you cry, but he also would make you laugh out of nowhere in the middle of it. That’s how I like to interview people. I will make a joke to them in the middle of it, which I think prompts them to bring their guard down and see me as a person. They realize that my intentions are pure, and then we can have an actual conversation, which is the thing that is missing from most journalism. I’m not trying to take something from my interview subjects, I’m trying to have them give me something.

What inspired you to devote an entire book to “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me” in the year of its thirtieth anniversary? Were you originally intending on dedicating an issue of The Blue Rose Magazine to it?

That is really funny because I hadn’t thought about it but you know what, you’re actually right. That is how it came to be. I knew that the thirtieth anniversary was coming up, and I had originally planned on devoting an issue to it. Then I thought, ‘Why? That should be a whole book,’ and that is how it came to be. It did sort of surprise me that it was coming, and it occurred to me when we did the April 2020 issue about the thirtieth anniversary of the “Twin Peaks” pilot.

The section of that issue in which series co-creator Mark Frost breaks down various key moments of the pilot is invaluable.

Mark Frost has been so good to The Blue Rose Magazine. When I spoke with him, he said that when they worked on the contracts, they actually carved out a space for The Blue Rose to exist so that Showtime wouldn’t shut us down. I was like, “What? You know about us?” He wants fans to have this sort of discourse and critique, and he wants it out there. It does help them, I think, to have us all trying to figure out what the hell Mark and David are trying to do.

The issue I was planning to have commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of “Fire Walk With Me” was becoming too big. Also, I don’t write The Blue Rose by myself. I have a spectacular team. Courtenay Stallings, John Thorne and I are managing editors, and then we have many other writers such as Matt Marrone, but I didn’t want to share “Fire Walk With Me.” I was really just being selfish. I was like, “I’m not going to say, ‘You cover the script and you talk to Sheryl Lee and you get the producer, Gregg Fienberg. I want to do it all!” [laughs] I had just turned in my book, Moonlighting: An Oral History, and I really didn’t want to start another book right away, but there was a deadline. The anniversary was only two years away, so I went right from Moonlighting into Fire Walk With Me, which was a little crazy.

How has the experience of writing this book deepened your appreciation of Lynch’s artistry?

The interviews did that for me. Half the book is interviews and the other half consists of my writing, and if I wrote book today, I could easily fill it with entirely new information because there is a wealth of it out there. Getting Ron Garcia’s stories was incredible. He was the DP, and he walks us through this David Bowie set that they couldn’t make because of money. It sparks your imagination to consider what Lynch wanted to do with it and how it would have changed everything. The main interviews in the book are with Ron, Gregg, Sheryl and editor Mary Sweeney. I learned things from them that I had never heard before and according to the feedback I am getting from readers, they haven’t heard either.

What inspired you to open up about the personal impact of “Twin Peaks” and specifically Sheryl Lee’s performance on your life in Chapter 11, which you wrote at the Salish Lodge & Spa featured throughout the series?

Sheryl Lee really made a difference in my life when I didn’t even know her because of her artistry that is on screen. I believe that what she delivers in “Fire Walk With Me” is the best female performance ever captured on film, and I love saying that because it annoys a lot of film people. I’m sure, here on RogerEbert.com, someone will say, “What about this other performance from 1927?” By all means, prove me wrong, cinephiles! But there is something about what Sheryl gave to that horrifying storyline that I don’t think other actresses would’ve felt compelled to do, which is mixed with her becoming an icon of that horrible tragedy. That has always moved me.

Most actors do a part and then move on. Kyle MacLachlan loves being Agent Cooper, but he’s not being cornered by people who have suffered a trauma and are crying to him in corners of buildings like they are with Sheryl. I don’t know of another role in which someone’s had to take that on, especially in a movie that was an absolute bomb upon its initial release. It’s not like Sheryl became Meryl Streep and won Oscars and makes a million dollars every time she shows up somewhere. What she does is create art for art’s sake, and as someone who wanted to be an artist but grew up in a small town where it just wasn’t an option to pursue that life, that has been a struggle for me.

So when I decided to write this book, I knew that I had to come clean. I had never really talked about why the movie mattered to me personally. My wife and I were on our first trip after Covid, and the first place that I wanted to go was Twin Peaks. We splurged and got the big room, the massages, the dinner, the whole thing. I went out on the balcony and I said, “I can’t put this book out and not be honest about why this matters. If I don’t write it here, I never will.” So I wrote that chapter on the balcony, and now it’s been published. Of course, no writing happens in one take. I just sort of puked it out and then edited through it. I hate that it’s out there, to be honest, because I’d rather be the comedian making “Twin Peaks” jokes, but I want to pay tribute to Sheryl. It’s not about me, it’s about Sheryl, in my opinion.

It’s a testament to the transcendent power of art in that you don’t have to have experienced abuse to connect deeply with her performance.

And it’s interesting how much people hated this film in 1992. That has been erased from society’s memory. Now everybody seems to love the film and David Lynch, but that wasn’t the way it was, and I think the reason people hated it is because it’s a true look at depression. He doesn’t hide anything, and Sheryl gave everything to it. Lynch and Sheryl opened themselves up for that criticism, but because it’s a good work of art, it lasted. You hate to compare anything to “Citizen Kane,” but in reality, “Citizen Kane” had a lot of haters when it came out, and now it’s usually picked as the #1 best film of all time.

How a work endures over time is the ultimate award. “Fire Walk With Me” is such a necessary part of the “Twin Peaks” series in how it cuts to the tragic heart of its subject matter, while inviting us to share in the perspective of its heroine.

I agree with you. What’s offensive to me is the first two minutes in every episode of “Law & Order” or “Bones” or “CSI” where they just find the young girl dead and no one cares. Everyone is fine with that because the show makes it digestible. Lynch doesn’t do that in “Blue Velvet,” “Fire Walk With Me” or “Inland Empire.” Any violence that happens to the female characters in those films feels real. You actually feel it and you want to look away from it like you are supposed to. You’re not supposed to go, “Ooo, this is fun. Pass me the popcorn!” I think people were not ready for that in the 80s and 90s. It has taken this long for people to see what he was doing.

I’d argue that Sheryl’s performance is as great as any I’ve seen on film. Is there a particular scene of her’s that sticks with you?

The scene that always comes to mind is the one that shook me. It’s when Laura runs out of the house, gets under the bush and sees her dad come out. There was something about the way she cries with her whole body that you just knew she wasn’t holding anything back. I feel that many times, actors are directed in a way that is way too mindful of how they look. You imagine the director saying, “We don’t want to make the audience feel too uncomfortable. Yeah, your kid died, but keep it together!” There isn’t any of that in Sheryl. The emotion she portrays is precisely what I felt while watching her in the theater, when I first saw the film at age 22.

It has taken me all this time to find out that Ron Garcia was worried about her and kept going up to her between takes to make sure she was okay. Gregg Fienberg told me that they changed the schedule after the train car scene to give her some time off, and Mary Sweeney talks about seeing Sheryl at the hotel at the end of the day, looking like she gave all of her strength during the shoot. It’s vindication, I suppose, to say that it is true what I saw, that she was giving more than most actors would. Now, when you talk to Sheryl about it, she won’t take any of that. She’ll say it’s all David. He brings that out on set with the direction he gives her, and I suppose there is some truth in that when you look at Naomi Watts’ performance in “Mulholland Dr.” and, of course, Laura Dern in everything.

Do you see shades of Jennifer Lynch’s extraordinary book, The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, in Sheryl’s performance?

Yeah, Sheryl said she read that book nonstop when making the film. She had notes everywhere. That was her guiding light, and she gives Jennifer Lynch a lot of credit for that. I remember reading that book in the summer of 1990. Up to that point, “Twin Peaks” was kind of fun. The pilot is very sad, but the show was not super, super-dark yet. I was less shocked by the Season Two premiere than the rest of America because I had read the diary. I knew that things were coming and that the show was tilting.

It’s interesting how Jennifer’s directorial debut, “Boxing Helena,” which got a great response at last month’s Lynch retrospective, received similar vitriol from viewers and critics upon its initial release.

My favorite line in my Fire Walk With Me book is not from me, it’s from Mary Sweeney and it’s a line that I hope people will cite when they are covering Lynch for the rest of time. She says, “David Lynch is an avant-garde filmmaker, meaning literally he is leading. He is out in the lead. He is forging a trail.” That is such a great explanation, and I think it is for “Boxing Helena” too. “Boxing Helena” was so far ahead of its time in how it dealt with issues that would be tackled decades later by the #MeToo movement. When you are ahead in that way, not everyone is gonna like it.

At the retrospective, the great editor Duwayne Dunham told me that he spoke with Lynch about why “The Return” would have to be more than nine episodes. Producer Sabrina S. Sutherland said, “It wasn’t until the very end that we found out how many episodes there were,” during your interview with her that was published in this month’s issue of The Blue Rose.

I think it just illustrates the fact that they had a script that was over 400 pages and they didn’t know what form it would take. The biggest misconception people have is that David Lynch had nothing to do with Season Two of “Twin Peaks” because he was editing “Wild at Heart,” even though that film came out the summer before the second season. Directors don’t normally edit a film six months after it is released. Anyone can google this, but people still say it all the time. You’re never gonna kill that lie. The other part of that Sabrina interview that I love is when she details how she and Lynch went through the script for Season Three with a stopwatch to figure out how long it was going to be. They’d go through a scene, and he’d be like, “Ah, that will take two minutes.” That’s crazy!

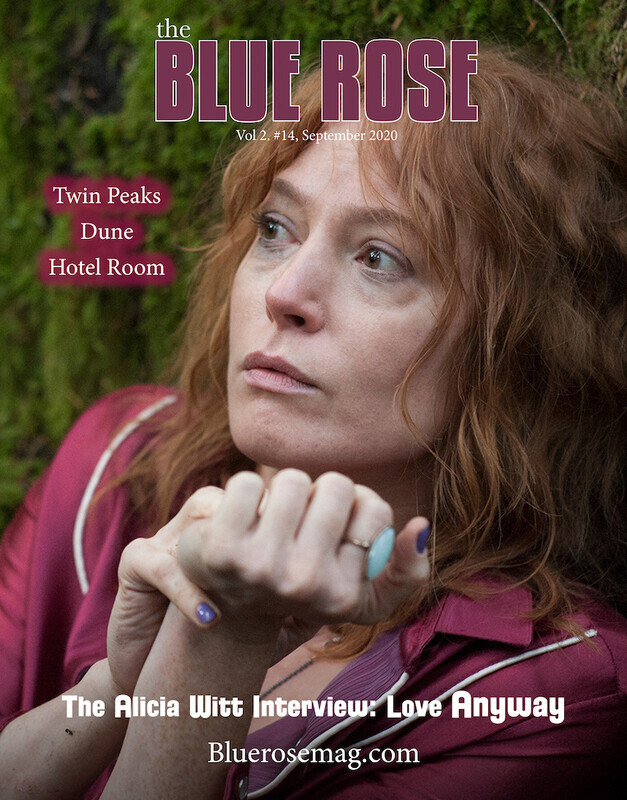

I loved your interview with Alicia Witt in the September 2020 issue, in which you discuss her performance in the “Hotel Room” episode, “Blackout,” which is also one of my favorites directed by Lynch.

I’ve been chasing Alicia Witt for a long time. I really wanted to interview her just because she’s someone that you hadn’t heard from regarding her experiences working with Lynch. When I finally connected with her over Twitter, she agreed and was honestly kind of like, “No one wants to hear about my work with David. Do you want to talk to me about being on ‘The Sopranos’ or my Hallmark movies?” I think she was really surprised that people were that interested in this, and I was like, “No, this is kind of a big deal.” That was a really big-selling issue for us because she hadn’t shared these stories before, and every one of them was a revelation. I could’ve talked to her forever because she has been in so many things, and she was super-nice. Her house had actually just gotten hit by a tornado before we were scheduled to talk, and she didn’t cancel! [laughs] I was like, “You know, if you get hit by a tornado, we do let you cancel,” and she was like, “No, it’s fine. I’ve got time.”

I think “Hotel Room” is one of those projects that had David just been given the opportunity to explore it further, what that would’ve become would’ve been incredible. With that being said, her episode is head and shoulders above the others, and it really is because of the chemistry between Alicia and Crispin Glover. She said that they basically learned it as a play. I told her, “If you and Crispin performed this now as a play, people would come non-stop.” It’s interesting because I can’t even say that I know what the episode is about. I feel like their characters are dying, and when that light comes at the end, that’s them going to the other side. Alicia didn’t feel that way—that wasn’t her interpretation—but my favorite story that she tells is that the episode contains her first kiss in all of life.

I interviewed the screenwriter of “Blackout,” Barry Gifford, last year, and he told me, “When I saw Alicia, she just looked like a little girl. Then I saw her perform, and she was brilliant. […] I also liked the fact that the characters were younger because it caused the loss of their child to be so fresh in their minds.” Of course, seeing them perform it at an older age would add a whole new layer of nuance to the piece.

It would. If you think of what that story is, it would play so differently with them being older.

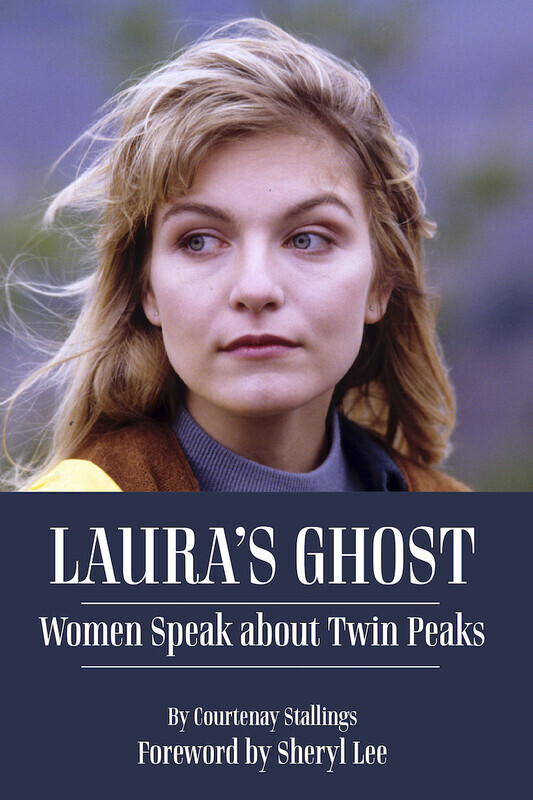

What importance does Laura Palmer hold for survivors of abuse, a topic that is explored so powerfully in Courtenay Stallings’ book Laura’s Ghost: Women Speak About Twin Peaks? Mary Reber, who played Alice Tremond in “The Return” and is the current owner of the Laura Palmer house, told me how people have opened up to her about how profoundly meaningful the character has been for them.

First of all, I always say that I have not been sexually abused and I could never speak for anyone in that way. But from my vantage point as I’ve gone around the country with Sheryl—Jen and I have been her handlers at certain events—I’ve seen people just come up to her and immediately share their experiences with her. Sheryl sees them, she knows them, she recognizes them. As the person managing her line, you get when Sheryl wants time with a particular person, so you give them some space and move them to the side. Sheryl will just hug these women. They want to tell her their story because they want to share it with Laura Palmer, and I think it’s because Laura wins in the end. This is a victim who defeats Bob, and that’s the importance of “Fire Walk With Me.” The strange part is, yes, she dies, but as she says in Season Three, “I am dead, yet I live.” She gets her angel at the end, while exuding complete strength.

When Laura puts on the ring, Bob appears to no longer have access to her body. She seems to be reclaiming herself at that moment, and one thing I have heard from numerous survivors of abuse is that it is essential to reclaim one’s sexuality on the journey toward healing.

What’s so fascinating is that Cooper says, “Don’t take the ring.” Cooper is wrong, but he is using the best information he has. People who don’t have forward thinking may say, “If the man said, ‘Don’t take the ring,’ therefore, it has to be true.” And you have to be like, “Well, maybe Laura knows more about what is going on than Cooper does, because she is the one experiencing this.” I do think that is her savior that gets her out, and it is extremely powerful. We were so honored to publish Courtenay’s book. That’s the bestselling book in our company’s history. It went over so well, and it’s because Courtenay gave all of those women a space to say what they needed to express. Not all of those women were sexually abused, but they all had stories of how they used Laura as a beacon of strength. Again, to beat up on “Law & Order,” “Twin Peaks” does begin with a young dead girl, but she becomes a hero, not a victim. That’s the legacy of “Twin Peaks,” not donuts and coffee.

In the February 2021 issue, you discuss the scene that was included in 2014’s “Twin Peaks: The Missing Pieces”—Lynch’s feature-length compilation of deleted footage from “Fire Walk With Me”—which explicitly states the meaning of the angel’s appearance at the end of the film, something most directors would have left in. Yet Lynch wants us to intuit its meaning, as a true artist does.

Yeah, because the first time I saw “The Missing Pieces,” I was like, “Why did he cut that? That’s why she gets the angel!” But then I realized how boring that ending would be if we knew an angel was coming the whole time. It was great that he cut it.

What inspired the August 2018 issue of The Blue Rose Magazine, in which forty characters from his films are each given an essay by a female writer, including Amy Shiels, who played Candie in “The Return”?

Courtenay Stallings was the managing editor for that issue. We stepped back and we let it consist entirely of women writing about the women they chose to cover. Probably the reason that issue is so good is that I had very little to do with it [laughs], but it’s an incredible read. All of these women from all over the globe contributed the essays. We even had a transgender writer, Erica Prieto, discussing the David Duchovny character, Denise Bryson, and what that meant to see a trans character back in 1991. Courtenay did a great job finding people who have eye-opening experiences, and from that, we did a Women of David Lynch book where we made it much bigger. That spawned a Women of series that we’ve done, with books focusing on “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” creator Amy Sherman-Palladino and “GLOW” creator Jenji Kohan. I want to do one about Quentin Tarantino. I think that would be great.

Women have always been crucial collaborators in Lynch’s work, with Catherine Coulson and Mary Sweeney being key examples.

Yes, and his partner right now is Sabrina S. Sutherland. She manages everything. It all goes through Sabrina and she is a badass woman. She doesn’t take any guff from nobody, but also, she has supported us so much. She’s bought every single thing we’ve ever put out, and has never asked for anything for free. She wants to support us and that says a lot about her character. I cannot say enough great things about Sabrina.

Why is Angelo Badalamenti’s score for “Fire Walk With Me” your favorite? Though you couldn’t get an interview with him, I love the quote he gave you that reads, “Scott Ryan’s writing and understanding of my music is unreal.” One example of that is your description of the film’s opening theme: “We have sex from the trumpet, fear from the synth and rock ’n’ roll from the plucking bass. What do you get when you mix sex, fear and rock ’n’ roll together? You get Laura Palmer.”

I always say that as much as I love “Twin Peaks,” I love the music from “Twin Peaks” even more. That is my favorite part of “Twin Peaks.” I have never written to any music other than what Angelo has composed. Whenever I happen to be writing, I always have a crazy Angelo playlist that is about fourteen hours long playing in my iTunes, and I just put that on shuffle. I’m sure that John Williams will go down in history as the greatest film composer of all time, and he probably is, but Angelo has a way of taking emotion and putting music to it. When I saw “Fire Walk With Me” that first time, as soon as the movie started, I would’ve bet everything I had—which wasn’t much at 22—that it would begin with the theme to “Twin Peaks.” You’d hear that bass, “Boom—ba-boom,” and that’s how it would start—and it doesn’t. It opens with music that makes you uncomfortable, and over time, that “Fire Walk With Me” theme has become my number one favorite “Twin Peaks” song.

I’ve always wanted to interview Angelo. He agreed to speak with me, and said, “Send me the questions.” I sent him twenty spectacular questions, and then he got ill. This was during Covid, and he said, “I just can’t do it,” so I wrote my chapter on his music. My deadline for the book was coming and I decided to send him the chapter. I asked Angelo, “Could you read this and just fact-check it for me?” I didn’t want to make a mistake. That quote you mentioned is what he gave back, and he said what I wrote was perfect. I was disappointed because I wanted my interview, but then I thought, ‘Look, he read this, and I made him happy. That should be enough.’

Every road trip my family took to visit my great uncle—who has a spirit akin to Alvin Straight, Richard Farnsworth’s character in Lynch’s 1999 masterpiece, “The Straight Story”—in Lowpoint, Illinois, was accompanied by the CD of Badalamenti’s score for that film. Roger Ebert captured its essence by writing, “The wind whispering in the trees plays a sad and lonely song, and we are reminded not of the fields we drive past on our way to picnics, but on our way to funerals, on autumn days when the roads are empty.”

I knew that if I sent Angelo too many questions, it would be bad, so nineteen of them were about “Fire Walk With Me.” But question number twenty was, “Can you get ‘The Straight Story’ released on vinyl, and can I write the liner notes?” I also think that score is incredible. People who think that all Angelo does is jazz are only thinking of his work for “Twin Peaks.” He is so much more than that, and there is none of that sound in “The Straight Story.” I agree that soundtrack is perfect, and the fact it hasn’t been released on vinyl is ridiculous. Disney, take a break from Marvel for one day and get that out on vinyl! They would sell out in one day.

To me, “Twin Peaks: The Return” is Lynch’s magnum opus that not only expands upon the first two seasons, but encompasses his complete body of work on the fortieth anniversary of “Eraserhead.” It inspired me to revisit Chris Rodley’s indispensable book, Lynch on Lynch, and two quotes from it directly connected to “The Return,” one of which you include in Your Laura Disappeared. It reveals how Lynch’s interest in incorporating time travel into “Twin Peaks” can be traced back to “Fire Walk With Me.”

Not to sound like Alvin Straight sitting on the porch and saying, “Get off my lawn,” but prior to that book, there was no information about “Twin Peaks.” So when Lynch talked in Lynch on Lynch about the scene where Annie appears next to Laura in bed and tells her what to write in her diary, that was big news, and I never have forgotten it. It’s funny that this concept stuck with Lynch all these years, and that’s really where “The Return” came from.

The other quote that stuck out to me occurs when Rodley likens Henry, Jack Nance’s character in “Eraserhead,” to Josef K in Kafka’s “The Trial.” Lynch responds, “Henry is very sure that something is happening, but he doesn’t understand it at all. He watches things very, very carefully, because he’s trying to figure them out. He might study the corner of that pie container, just because it’s in his line of sight, and he might wonder why he sat where he did to have it be there like that. Everything is new. It might not be frightening to him, but it could be a key to something. Everything should be looked at. There could be clues in it.” To me, that is a spot-on description of Dougie Jones, who at one point mirrors the iconic shot of Henry in the elevator.

There is a ton of Lynch in “The Return.” It is kind of the exclamation point on his career. I do make some jokes in the book about Season Three because if you love something, then I am going to tease it. I’m a Gen Xer, and that’s how we were raised. Biting every hand that feeds me is my nature. We are working on a David Lynch Encyclopedia that’s going to come out in a couple years, and I’m writing about “The Straight Story” for that book. I’m actually going to compare Dougie to Alvin Straight, because wherever Alvin goes, he creates kindness out of the person that he interacts with. You always think that something bad is going to happen. You think that girl who comes up and wants to have dinner with Alvin at the fire is going to steal his stuff, but what occurs between them instead is kindness, and the same thing happens with Dougie. Everyone Dougie comes in contact with, he actually turns them to be kind. I never really considered Dougie and Henry beyond the shot of him in the elevator, which is definitely the same, but I think you’re right about that quote from Lynch connecting them too.

As Lynch said at a book signing for Catching the Big Fish prior to the Chicago premiere of “Inland Empire” in 2007, “My films are like Certs breath mints—two in one!”

[laughs] That’s right! At the Q&A in Chicago, I thought it was very interesting that Duwayne Dunham said, “Lynch will never tell you to cut here. He’ll give you a direction like, ‘Make it more yellow.’” There is that feeling in all his films, and that’s why we go back to them. We don’t want answers.

In what other ways do you consider Lynch’s work therapeutic? I think this quote from Lynch singled out by John Thorne in his excellent essay, “Time & Time Again,” contained in the March 2018 issue summarizes this beautifully: “Our trip through life is to gain divine mind through knowledge and experience of combined opposites. To reconcile those two opposing things is the trick. In order to appreciate one, you have to know the other—the more darkness you can gather up, the more light you can see, too.”

John Thorne is a master at Season Three. He knows all of “Twin Peaks,” but nobody knows Season Three better than John. Whenever one of his essays comes in, everyone is excited to read it. As for why I find Lynch’s work therapeutic, it’s because the space left on the screen is for you to fill. It makes all the difference. You are never going to have a David Lynch character spout the sort of exposition that makes you want to vomit when you’re watching it. Lynch doesn’t care about the plot. The plot means nothing to him, so as a viewer, all you can do is put yourself in there. You have to fill the blanks with yourself.

The introduction to my book is a tongue in cheek look at what I call “Lynchsplaining.” I just let people know that if they picked up this book thinking that I’m going to explain “Fire Walk With Me,” you’re crazy. I can’t do that. Only you can explain what you get out of it. That’s the fun of it, and that’s why it’s therapeutic. Every missing detail that the bland movie viewer is annoyed at, you fill in with your own psyche. That’s why we can have these great debates where to you, when you see Dougie, you see “Eraserhead,” while I see Alvin Straight.

I liked how you said in your recent conversation with Sabrina S. Sutherland that the ideal way to experience “Twin Peaks” is by watching one episode per week, allowing you to ruminate on each of them. It was thrilling for me to experience “The Return” like this with no episode recaps nor any idea of who was going to show up on any given episode.

The best show on TV right now is “Severance,” but there is an episode that begins with a title card which spoils a key plot point in the last scene. All of those things you mentioned about “The Return,” such as the absence of recaps, are the result of Lynch loving what he does. Most people who are putting out movies and TV don’t really love their work. What they love is money, and they want to do whatever they can to make as many people watch their work as possible. Lynch doesn’t give a rat’s ass if you watch his work. He likes when people like it, but that’s not his goal. You don’t have a character sweep a floor for three minutes on television if you care about the average guy watching.

And I love that sequence because it seemed to reflect how everything was starting to come together at that point in the story. Lynch likes to allow for those moments of meditation, which were invaluable to have during the chaotic year of 2017 with its streams of “alternative facts” forming parallel realities. It was as if Lynch was telling us to take a moment and think before we act.

It really is crazy that they wrote the script before any of that happened, because it did seem to speak to that precise moment. To me, the line of all Season Three is from the Mitchum brothers when they say, “People are stressed out there.” That’s how we felt so much at that time when everybody was being bombarded by the worst news you’ve ever heard, and it’s still going on now. That’s why I always call it the Summer of Peaks.

In college, I assisted Richard Hoover—the production designer of the original “Twin Peaks” series—on the set of Terry Kinney’s short film, “Kubuku Rides (This Is It).” His stories about working with Lynch reminded me of how Mel Brooks famously dubbed the director “Jimmy Stewart from Mars.”

That is a really good description of him. To me, Lynch is just an artist in the truest form. We don’t really have pure artists anymore. There aren’t Rembrandts or Picassos out there, and Lynch is one of those people. Of course he wants money—everybody needs food and a home—but that isn’t why he does these things. He gets an idea and he needs to get it out of his head. He doesn’t really care what you think of his idea, and that’s a brave way to be. I don’t know that he has a peer in that way, and whenever somebody tries to do something Lynchian, it’s always horrible. He’s not trying to be anything other than himself.

Is Lynch resistant to being interviewed for The Blue Rose?

When we did the issue about the thirtieth anniversary of the “Twin Peaks” pilot, I asked, “Could David just give us a quote about thirty years?”, and received a response that stated, “No. David knows you do a magazine, he is glad you do a magazine, he doesn’t want to be part of the magazine.” I’ve never asked Sabrina for him or anything from him. He’s not really someone that I’m dying to interview because he’s not really going tell you anything. I’m not gonna ask him what the frog moth means in Part 8 of “The Return.” I would just want to have a discussion with him.

At the retrospective in Chicago, Daniel played some amazing interviews where people were so mean to him. He screened one before “Blue Velvet” in which a lady asked him, “Are you a psychopath?”, and I thought, ‘Huh, that lady is the reason why I can’t get an interview with David Lynch.’ Why would he put himself through that? But I know that Sabrina shows him the magazines and the books. He knows about what we do, and that’s good enough for me. I don’t know that it would be that great of an interview as far as actual content. It’s the writers, the editors and the producers that you get the really good stories from.

The fact Lynch appreciates your work is probably the best endorsement you could hope for.

We’re as small of a company that’s possible in the world. Lynch or Showtime or CBS could squash us like a little bug—and they don’t. They support us. They are glad we exist, and in 2022, that is incredible, especially when you see what franchises like “Star Wars” do to its fans. They just shut you down, and we are given access. Harry Goaz, who plays Deputy Andy, doesn’t give interviews. I was at an event with John Thorne, and Harry was there. I went up to him and said, “Hey, I’m Scott from The Blue Rose, I would like to interview you.”

He just looked at me, and I said, “I know you don’t give interviews, but here’s the thing—you gotta give one interview, and then people will be like, ‘Why did he give that one interview?’ That makes you a mystery. Giving no interviews doesn’t.” And he said, “You know what? I’m gonna do the interview.” He said he’d heard of The Blue Rose and he knew that we were okay. I feel that in the “Twin Peaks” community, people realize that we love the work and we’re just trying to cover it while they’re all still here.

Daniel Knox’s Lynch retrospective was completely devoid of the toxicity that seems to have infiltrated other fan communities. It’s a testament to Lynch’s work that it attracts people who are open to empathizing with the characters onscreen rather than knocking them down.

I agree. Way back when, I wanted to write a book called Fans and Festivals, with a play on the word “fan” to reference both the ceiling fan in the Palmer house as well as the fans that attend these sorts of events. I wanted to interview different fans of the show because I was so fascinated by the fact that if I found out that someone likes “Twin Peaks,” I probably could be friends with them. That’s not true of “Everybody Loves Raymond.” There is an overall pain in Lynch’s work. To accept the pain that is on the screen means that you are a caring person, and so you are bound to meet other caring people. I didn’t know you before the retrospective. My wife and I met a couple there, and they invited us to the renewal of their vows in October. There were people among the attendees who I talked to every day, and we had great conversations. Lynch opens the mind and the heart.

You can see the care that is put into each of the Blue Rose issues, all the way down to how they are packaged.

We want to give a good product, and we try our best. I write them, I design them, I get them printed, I package them, I put the stamps on them and I take them to the post office every day. My whole life is about getting these books and magazines out. I certainly have a great team, but all the paperwork stuff just happens out of my little house. It’s an honor to get to do this, and I wouldn’t be able to do any of it without my wife. She’s got the corporate job that keeps us floating while I’m out here writing and starting these silly little companies. [laughs] I know that I am lucky.

Fire Walk With Me: Your Laura Disappeared is available to order here. For more information, visit the official sites of The Blue Rose Magazine, Scott Ryan Productions and the Fayetteville Mafia Press.

Matt Fagerholm is an Assistant Editor at RogerEbert.com and is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.