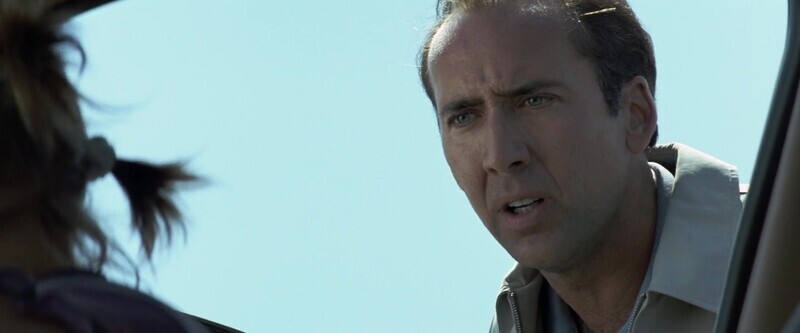

“He’s scraping at the door ... and I’m gonna let him out.”

- Johnny Blaze, “Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance”

This year will see the release of “The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent,” starring Nicolas Cage in the one conceivable role he hasn’t yet tackled: himself. Leading up to the opening of this house of mirrors and meta text, I watched every single movie starring Mr. Cage, a task that truly began when I was a starry-eyed kid watching “Con Air” and “The Rock” in theaters with my dad. I thought I had Cage figured out then, but he’s thrown so many curveballs, and he’s rewritten what an actor’s career can be in this desperate and odd time for American movies. There are some actors we watch because we want to see the result of months of internal calculus as they’ve wedged themselves into a new shape; a new person that could only have resulted from this actor taking this assignment. There are some actors we watch because they find stores of undeniable emotion in each character, no matter how small or vile; they will get us to understand that which we might never otherwise. There are some actors we watch because they’ll make a meal out of every performance; tics and affectations stacked like a closet full of board games. We watch Nicolas Cage for all of these reasons and more. We watch Nicolas Cage because there is no one else who does what he does. He can vanish into a character; he can make a character vanish into him. We watch Nicolas Cage to see an animal force unleashed upon lives, to see what form its highly unstable energy takes, to see the demons in him leap out of darkness and into each body he possesses.

No matter how often the industry seems fed up with his authentic-seeming lunacy, his money problems, his inability to let a movie’s tone get in the way of his art, Cage hangs on, fittingly, like a vampire bat. Between the Actors Studio method reign of Marlon Brando, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger, and James Dean and the mythic transformations of Christian Bale, Jake Gyllenhaal, Daniel Day-Lewis and others emerged Cage, an impossible mix of Warren Beatty, John Wayne, and Richard Widmark. Born to Hollywood royalty he emerged a game and lovable fixture of the New Hollywood hangover period. Whether he was playing inscrutable toughs for his uncle Francis Ford Coppola or sensitive hoods for Martha Coolidge, he seemed someone with a bottomless well of feeling. In Alan Parker’s overdetermined “Birdy” he breaks down at the sick bed of his brain damaged best friend. “Come on, Birdy!” He cries, tears in his eyes, voice breaking, a young man unable to comprehend what life had done to someone he loved so much, who seemed so full of life.

Cage never seemed to lose the refreshing elixir that powered his anti-heroes. He could always rebound no matter what a scene partner or script threw at him. He’d been in a half dozen modern classics before he was given the chance to be a leading man. The unremarkable “The Boy in Blue” was his first, but what followed change the American cinema, his life, and ours. “Raising Arizona” was the first of the classic Cage leading man performances. He’s a marvel of drawling self-deprecation, a man who was happy with the nothing that was his birthright until he met the woman he loves. H.I. McDunnough, hair like a mushroom cloud, is a perfect meeting of the Coen Brothers sensibility and Cage’s ego-free performance style. He’s the Coyote from Chuck Jones’ Roadrunner cartoons, blown to pieces in pursuit of a better life, but always able to get up again in the next edit.

In Coppola’s “Peggy Sue Got Married” released a year before “Raising Arizona,” we see the first unleashed Cage performance. Embarrassed by the material his uncle gave him, he played lovesick Charlie Bodell as a coked-up Eddie Deezen, the weightless counterpart to Kathleen Turner’s grounded hero. Every line reading comes with some hitherto unheard pronunciation and breathing pattern. He seemed to be reinventing what it could be to act for a camera. Even now the performance is polarizing. James Agee wrote that Ray Milland’s performance in “The Lost Weekend” is “debatable at first, but so absorbed and persuasive as the picture moves along ...” That became Nicolas Cage’s marching orders. Make choices so absurd that only a fool would think to trot them out for all to see, but stay so fiercely committed that by the end you’ve won over the doubters and scolds. The cinema would become his playground.

While he would settle down for most of the ‘90s playing lovable schlubs in everything from volatile Michael Bay action movies like “The Rock” to Andrew Bergman comedies “Honeymoon in Vegas” and “It Could Happen to You,” there was a secret Cage career exploding in the margins. For every thankless “Trapped in Paradise” or “Firebirds,” there was an unhinged performance you had to work to find. If Elvis had reached his full potential as a screen actor, able to put the fear of god into his audience like he did on stage, he’d have done the work Cage does in “Moonstruck,” “Wild at Heart,” and “Zandalee.” (Well, maybe not “Zandalee.”) Cage struts like a rockabilly chicken hawk up and down the alleys of these overheated melodramas, leaving rubble and moaning admirers in his wake. Though I suspect not even Elvis could have so eloquently sold a screamed “I lost my hand! I lost my bride! Johnny has his hand! Johnny has his bride! You want me to take my heartbreak put it away and forget it?” It helped that he was gorgeous, but the shockingly charming performer seemed to grab the filmed image and eat it with both hands. In the bargain basement Tennessee Williams knock-off “Zandalee,” he plays an oversexed ne’er-do-well who steals his best friend’s girl early and often. They have sex on the street, in the laundry room during a dinner party, even in church, where he tears his shirt open and cries “Shit! F**k! Strike me down lord!” In David Lynch’s secret masterpiece “Wild at Heart” he croons “Love Me Tender” between bouts of what Rod Kimble would call punch-dancing and athletic sexual congress with an electric Laura Dern. In these performances, it was like his soul was trying to claw its way out of his body.

Cage thus split his work into three camps for the next several years. He could do aggressively normal guys in over their heads (think 2005’s “The Weather Man” or the brilliant “Red Rock West” from 1993), fire-breathing lunatics (as when he screams the alphabet or eats a live cockroach in "Vampire’s Kiss," neither of which is even the wildest scene in that movie), and the performances you couldn’t hope to describe. Usually these are for friends or family who are getting him cheap. In Adam Rifkin’s “Never on Tuesday” he arrives for literally a seconds-long cameo and manages to upstage the main cast with his surreal appearance and bizarro vocal inflection. In his brother Christopher Coppola’s 1993 movie “Deadfall” he showed up to set to play a vicious gangster in a Tony Clifton wig and a zydeco bandleader’s speech patterns. Despite ample proof that Cage could shoot a film into outer space, none of his absurd antics on set or off (the pyramid he bought in New Orleans, naming his son Kal-El) ever stopped him from being one of the most bankable stars in America. He won his Oscar for “Leaving Las Vegas” (perhaps his least interesting performance) the same year he played a tatted kingpin who bench-presses his girlfriend for exercise in Barbet Schroeder’s amazing “Kiss of Death.” Two years later he was supposed to be the only normal guy in “Con Air” and an honest-to-god Angel who romances Meg Ryan. He opens 1997’s “Face/Off” by playing a human supernova, more hyena than man, but closed out the decade giving one of the best central performances in any Martin Scorsese film in “Bringing Out the Dead.” You couldn’t stop him.

It’s tough to pinpoint exactly when things changed for Cage. After a full decade carrying blockbusters like “National Treasure” and “Ghost Rider” and family dramas like “Matchstick Men,” his willingness to poke fun at himself was weaponized against him. The start of internet culture announced a humorless approach to Cage’s mid-career slump. As he showed up in the earnestly terrible (“The Wicker Man”) and the terribly earnest (“Knowing”) it seemed like financiers were getting sick of him, and people had reduced him to a joke. The movies got sillier (“Next,” “G-Force,” “Bangkok Dangerous”) and smaller. By 2010, his big-ticket movies (“The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” “Drive Angry”) were seen as too self-aware for their own good. This is the start of his direct-to-video period, where the culture turned on him, and it was seen as a minor miracle when he showed up in anything high-profile. Personally, this is when I fell most in love with him. Others saw an actor with money problems slumming in DTV crime movies. I saw an artist trapped in a prison cell trying to paint the walls. Or maybe more accurately, his beleaguered paramedic in “Bringing Out the Dead,” begging to be fired but too talented and too unafraid for him to be cut loose. In movie after movie, he’d bring more to the table than you expect. The three strands of his acting merged into one. I started collecting the most outre scenes from the raft of VOD releases from this period. There’s the way he melts down at the end of the aggressively minor “Rage,” the few seconds he becomes a cartoon character in the magnificently silly “Stolen,” and the way he drinks tequila in the already forgotten “Kill Chain.”

People, I think, grimace a little when they hear about new Cage movies. But not me, because I know the quality of his performances never fully dropped off. Even while appearing in “Left Behind” and “211,” he would still get hired by discerning directors for performances with no little gravitas. David Gordon Green’s melancholy crime film “Joe” came out in 2013, the thick of these years, and that’s about as good as Cage has ever been. The low point for me was “Pay the Ghost,” a dreary horror-thriller in which he looks puffy and sad. I was worried then that he wouldn’t rebound. I shouldn’t have. The thing about making straight-to-Netflix thrillers is you get to have fun. In the risible “Arsenal,” he resurrected his be-wigged character from “Deadfall” because well ... it was a funny idea that made the movie worth watching. In 2017’s “Inconceivable” he makes not speaking into gestural high art. In the movie “A Score to Settle” he sings and plays the piano, showing genuine vulnerability and an eagerness to please all the while freely expressing himself however he wants. He isn’t even that raw in “Leaving Las Vegas.” Of course, because he’s still Cage, he ends the movie with this scene, a little box of treasure for fans of his expressionism.

Cage hung on through lean years with meagre characters and it paid off. In 2018 he had a breakthrough. He fulfilled a lifelong dream to play Superman in the Teen Titans movie, he was put in the maximalist “Mandy” which gave him a huge boost, and he gave an unbelievable performance in the little seen “Between Worlds.” In the latter film, he plays a stoner truck driver caught in a supernatural romance; the movie features many scenes of him just hanging out and loving life. It was good to see him look like he was really and truly enjoying himself. The movies have had better attitudes in the years since. In “Color Out of Space” he sneaks in a bizarro call-back to his performance in “Peggy Sue Got Married,” but for the most part delivers a credibly sorrowful turn as a man who loses everything. He had his latest big Sundance premiere with Sion Sono’s bonkers “Prisoners of the Ghostland” earlier this year, a rousing success on its own terms.

Watching “Prisoners of the Ghostland,” a canny navigation of what he does well and what people expect from him, I found myself perversely proud of this man I’ve never met and do not know. He started as a heartthrob who wanted to be more, an honest to god star, and he did it. Then he lost it. He gained weight, lost his hair, lost his studio contacts, lost his franchises. But then, just when it seemed like he would be lost in a sea of bad press and internet ridicule, he pulled himself back from the abyss. In “Ghostland” he’s in great physical shape, he manages a legible emotional journey in the middle of a zany yakuza western hybrid, and he still has his sense of humor. I thought back on his whole career, from the old-time analyst in “Snowden,” the man who’s seen it all, to the Jimmy Stewart impressions that creep up on him during his steely and fearsome performance in Werner Herzog’s brilliant “Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans,” and Paul Schrader’s “Dog Eat Dog,” to his turn as Fu Manchu in Rob Zombie’s “Werewolf Women of the SS,” all the way back to his heartbreaking hunk in “Valley Girl.” I saw a survivor.

He’s a man with instincts that told him to go big, to be the incendiary man on the edge, a meteor pointed at his audience. His enormity, his good-natured goofiness and rabid method externalized pain—at any time it could have sidelined him completely, but there’s too much honesty there and there's too much intrinsic to the success of cinema as an art form. Brando, Dean, Widmark, Toshiro Mifune, Alain Delon, Stanley Baker, Joan Crawford, Bette Davis—pick your actor auteur and try to imagine our culture without them. Cage is in that group. His best was some towering reactor meltdown of all the largest impulses in American screen acting, a man who could be huge and who could be so achingly small but a man who would not be stopped. Cage surrendered his path to a normal life a long time ago, and yes he did it because it opened doors for him, bought him that pyramid, sent his kids to school. But more than that he did it for the audience who never lost their thirst for his Elvis-inflected hand gestures, for his thousand-mile stare, for his voice like a dust devil. He did it for us. He did it for me.

Scout Tafoya is a critic and filmmaker who writes for and edits the arts blog Apocalypse Now and directs both feature length and short films.