Thumbnails is a roundup of brief excerpts to introduce you to articles from other websites that we found interesting and exciting. We provide links to the original sources for you to read in their entirety.—Chaz Ebert

"Elisha Christian on 'Columbus' and 'Everything Sucks!'": The Spirit Award-nominated cinematographer chats with me about his acclaimed work on Kogonada's 2017 film and this year's acclaimed Netflix series.

“[Indie Outlook:] How did you and Kogonada develop the extraordinary shot of Jin (John Cho) and Eleanor (Parker Posey), framing them in a mirror in a way that gives us a sense of their history. We feel as if we are peering into a reflection of their past.’ [Christian:] ‘That scene took place in the same inn where Jin was staying. There were only four or five guest rooms in the whole inn, and we had our pick of which room we wanted to shoot in. That location is so visually interesting — you could shoot a whole movie there. When we saw the mirrors, we knew where we wanted to place the camera, though my AC couldn’t even stand next to it to pull focus. She had to sit underneath the camera while reaching up above her head to pull focus because the space was so slim. We even had to pull everything off the sides of the camera in order to fit in that tiny area without catching it in a reflection. We saw that if John walks out and stops at a certain point after Eleanor basically kicks him out, he could turn back to her and we’d be able to frame them both in an interesting way. It was definitely a dance. I remember that we were running behind that night. It took a while to set up the shot and get it ready, and we probably shot about 7 or 8 takes of it. We had two other shots planned in the scene, but when we got the take that Kogonada wanted, he said, ‘We don’t need the other shots.’ That’s a ballsy decision, considering the length of the scene. It’s decisions like these that made the movie better.’”

"Peak superhero? Not even close: How one movie genre became the guiding myth of neoliberalism": Brilliant commentary from Salon's Keith A. Spencer.

“Obversely, this is precisely how politics functions in neoliberalism: Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were presented as branded superheroes, who believed they knew what was best for us, and sought to install their elite wonks to enact their benevolent (to them) policies. There’s a relatively two-dimensional view of the world at work: there are good and bad people; they are generally born that way and seldom change. The state in neoliberalism and superhero movies is almost entirely devoted to oppression and surveillance. If the state overreaches, heroes must fix its excesses; if it fails to protect its citizenry, heroes must make up for its shortcomings. In either case, its social welfare function is invisible: because people are innately good or evil, there are no social workers or teachers or other welfare-state employees whose duties might prevent villainy (or supervillainy) through social work. Superheroes are, by definition, more powerful and more important than the state. More importantly, the superheroes’ work may save lives, but it never inherently changes the relationships of production: If the people are poor, they’re likely to stay poor. They don’t participate in redistributive politics except to attack the sort of universally detested social relationships about which there is broad consensus — for instance, slavery. Superheroes can’t and won’t save the middle class; many of them are rich anyway and stand to benefit from the kinds of inherent economic injustices that, say, Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn fight against.”

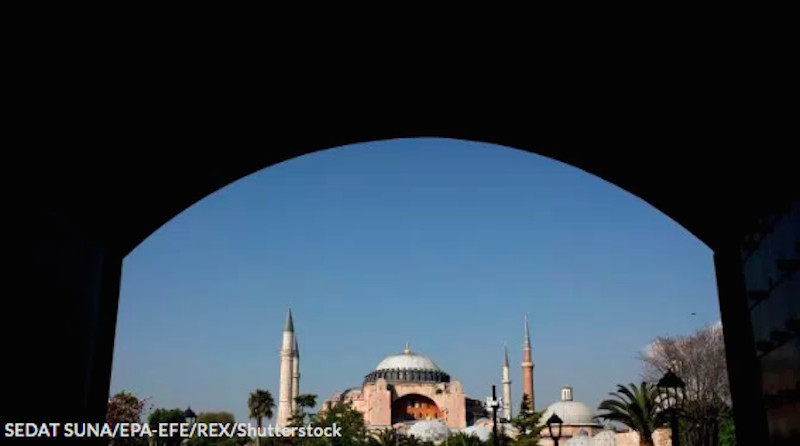

"Turkey's Government Is Censoring the Movies, But the Istanbul Film Festival Is Soldiering On": According to Indiewire's Amy Nicholson.

“No one is sure what the moral rules are. The Ministry of Culture won’t write them down. At least the Hays Code in classic Hollywood had 11 clear don’ts. Specific rules can be subverted. But Turkey’s veto power is capricious and vague. Filmmakers, especially documentary filmmakers telling unflattering stories about modern Turkey, could spend years on a movie that can’t be shown. Unpredictability pressures artists to play it safe. Some hire lawyers to help them guess whether their work might be rejected, and if so, hunt for foreign producers willing to take a controlling stake as international films don’t require a certificate yet. But as Saudi Arabia opens its first movie theater in 30 years with a screening of ‘Black Panther’—imagine women who finally got the right to drive this year beholding the Dora Milaje—Turkish people are alarmed that their government, which just disrupted the last major dissenting newspaper chain, threatened people over their footage of Taksim Square, intermittently shut off YouTube and Twitter, and is poised to ban teaching evolution in schools, is making it hard to share their stories with the outside world. Over a bottle of wine, a director sighed as she pointed toward the west, ‘News comes one way.’ The impact was everywhere. ‘I can say that there are less political movies than before,’ said current festival director Kerem Ayan on a group boat trip circling the Bosporus River. ‘But cinema is very creative. Everybody finds a different way to express what they want.’”

"The Résumé: The Winding, Everlasting Career of William H. Macy": Another essential interview conducted by Sam Fragoso for The Ringer.

“I had never done anything that graphic or that sexual before ‘The Cooler.’ I’d taken my clothes off, but that’s different. And it was my adorable wife who finally said, ‘When you talk about it, it sounds like you’re planning to fail. If you don’t want to do these sex scenes, you should call the director and tell him you don’t want to do them. If you do want to do them, you better start thinking about how to make them great.’ It was a fabulous wake-up call. I married well. So I started to look at the sex scenes like any other scene—as an acting exercise. What’s different at the end of the scene than at the beginning? What happened? What’s the objective? What transpired? Where’s the moment where something changed the plot even though we’re just rolling around in bed? And to Wayne’s credit, I said, ‘I can’t understand the scene. I’m having trouble here. What happens here?’ And we talked about one or two scenes and he said, “You know what, you’re right. I can’t find it either.” And he cut them. He cut the scenes. Which is sort of the essence of art, I think: If you can cut it and still tell your story, then you have to cut it. I was shy but Maria didn’t care. She said, ‘I’m an old hippie. This is nothing.’”

"50 Years Ago, a White Woman Touching a Black Man on TV Caused a National Commotion": Petula Clark and Harry Belafonte chat with Vanity Fair's Donald Liebenson about the moment that erupted into an inadvertent scandal.

“For his part, Belafonte thought there had just been a technical glitch. He did not think the touch was problematic: ‘Quite the contrary,’ he says. ‘I was quite pleased. That song, if I remember, was the last thing we shot. There was an enormous sense of release that we had pulled this off without a hitch. It was one guy—Doyle Lott—who said we had to re-shoot what we had just done. We were nonplussed as to what was the problem.’ NBC, alerted to the controversy, called Binder to say the network would back him (‘That was a great phone call to get,’ he says). With that, Binder and Wolff rushed to the studio basement to confront the editor and order him to keep the take where Clark touched Belafonte’s arm—and to erase the others so they could not be used in the broadcast. Somehow—Binder doesn’t recall what did it—word of the controversy got out early, resulting in breathless pre-broadcast news coverage. ‘Incident at TV Taping Irks Belafonte,’ said a March 7 headline in ‘The New York Times.’ The article quoted a statement from White: ‘If there was any incident . . . it resulted solely from the reaction of a single individual and by no means reflects the Plymouth Division’s attitude or policy on such matters.’ Lott’s Detroit office also issued a statement: ‘I was tired. I over-reacted to the staging, not to any feeling of discrimination.’ Binder remembers hearing that Belafonte was about to tell America to boycott Plymouth on ‘The Tonight Show’; he called the singer to tell him it wasn’t the car company’s fault, and reminded Belafonte of his conversation with White. On March 10, the ‘Times’ reported that Lott had been ‘relieved of his responsibilities.’”

Parallax View's Richard T. Jameson lists his favorite "moments out of time" from films he saw in 2017, including Bertrand Bonello's "Nocturama."

Alexander Jeffrey's short film, "An Aria for Albrights," stars Laura Bretan, the astonishing young opera singer who became a 2016 finalist on "America's Got Talent." Click here to read my interview with her at Indie Outlook.

Matt Fagerholm is an Assistant Editor at RogerEbert.com and is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.