Now streaming on:

Many of the most powerful documentaries in recent memory have been made by young filmmakers attempting to confront troubling issues within their family that have long been buried under the surface. The bar was set for these achingly personal pictures in 2018 by Bing Liu’s “Minding the Gap,” which surely ranks among the greatest films of the 21st century. When asking his mother painful questions about decisions she made that endangered his well-being, Liu sits next to his camera while ensuring that a lens is placed on his face as well. This isn’t a technique in line with reality show-style manipulation, but rather a method for the filmmaker to hold himself accountable, making his vulnerability as palpable as that of his subject so that we can sense the complexity of his own perspective. We can clearly observe the emotional obstacles that register on his face, blocking his path toward forgiveness. In a way, these scenes turn the camera on us, forcing us to relinquish our roles as passive observers by acknowledging the ways we have shaped our own family narratives, and how they may have prevented us from absorbing the full scope of their truth.

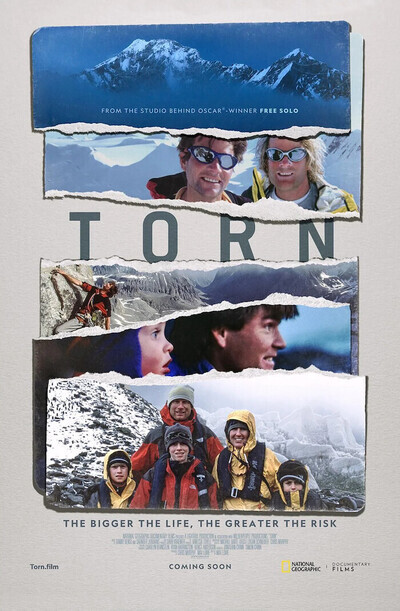

Two of 2021’s best nonfiction works have explored the chasm left by an absent paternal figure in the lives of those he left behind following his untimely death. Ry Russo-Young courageously sought to understand the mind of her mother’s sperm donor, Tom, in her three-part HBO miniseries, “Nuclear Family,” where she attempted to untangle the complicated feelings that prevented her from furthering her relationship with him, as a result of the custody battle he waged. Now we have the equally piercing and viscerally emotional film “Torn” from first-time feature director Max Lowe, whose father Alex was a celebrated mountain climber renowned for his skill as a “risk controller.” On October 5th, 1999, Alex’s death was triggered not from a fall but an avalanche that occurred while he was scaling the world’s fourteenth highest mountain, Shishapangma, in Tibet. The bodies of Alex and his cameraman David Bridges were nowhere to be found, leaving the late icon’s closest friend and climbing partner, Conrad Anker, to stumble back to their tent in a shell-shocked daze.

One of the great achievements of “Nuclear Family” and “Torn” is in how they chip away at the larger-than-life labels placed on these men—in Tom’s case, a villain, and in Alex’s case, Superman—to reveal the all-too-human being underneath. Alex’s widow, Jenni, admits that she was attracted to the characteristics of her husband that were reminiscent of a “wild animal,” refusing to question her feelings for him just as he never faltered in his pursuit of adventure, choosing to spend Christmas in the wilderness of Antarctica rather than at home with his family. It was with this same instinctual sense of direction that three months after Alex’s passing, Jenni found herself falling for Conrad, who had once been the subject of Alex’s envy in his lack of familial responsibility. The guilt Alex felt about neglecting the needs of his boys had been transferred onto Conrad, wracked with the seeming unfairness of his survival and determined to be the father that his friend wasn’t able to be in life. This began with fulfilling Alex’s dream of taking his children to Disneyland, and the footage Conrad filmed of little Max squealing blissfully on a rollercoaster is one of numerous times in which “Torn” reduced me to tears.

In light of the film’s subject matter, not to mention the fact that National Geographic is distributing it, one naturally expects this picture to be loaded with breathtaking landscapes, and indeed it is, yet the most unforgettable sights witnessed here are the expressions that materialize on the faces of Max and his family members as they begin to reach a hard-earned sense of peace and catharsis that has taken them well over a decade to embrace. As a filmmaker, Max is rigorous in portraying his inability to accept Conrad as his father, having been attached to Alex much more than his younger siblings, Sam and Isaac, who lack any resonant memory of their biological dad apart from what they knew of his achievements. When Isaac pointedly asks Max why he’d want to make a film about aspects of their lives that they haven’t yet adequately dealt with themselves, his words caused me to reflect on how the lens of a camera enables us to face the very things from which we’d otherwise shield our gaze. Though much about Alex and his motivations remain enigmatic even to his own immediate family, it’s worth wondering whether the persistent presence of a camera provided him with a sense of comfort when venturing into the unknown.

The last thing we hear in “Torn” is an exhalation of breath for which no additional words are needed. So intimate are the interactions captured by cinematographers Logan Schneider and Chris Murphy that never for a moment do we feel as if a meaningful word or glance is staged. The implicit trust that appears to have been built between the subjects and crew brings us as close to their personal journey as possible, and it is to the credit of Max that nothing intrudes upon it. There are times in which the score by Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans swells, but never in a way that overrides the emotional truth embedded within the footage. It also knows when to preserve the sacred silence of moments where we are able to feel the weight of the family’s loss. I could write a great deal about what occurs in the film’s last half-hour, but I’d rather have you discover it for yourself. What I will say is that “Torn” elicits tears in a way that is raw, unexpected and wholly earned. By inviting viewers to share in the most private of transformative periods for his family, Max Lowe scaled the Mount Everest of the soul, creating a cinematic gift that cuts to the heart in ways few films ever do.

Now playing in select theaters.

Matt Fagerholm is an Assistant Editor at RogerEbert.com and is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association.

92 minutes