Now streaming on:

In Shakespeare’s As You Like It, written around 1599, the character Jacques declaims on the “seven ages” of man, starting off with a “mewling and puking” infancy and ending on a rather dreadful vision of old age: “second childishness and mere oblivion; sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” Some 400 years later, according to Kingsley Amis, Amis’ friend the historian Robert Conquest penned a limerick distilling Jacques’ speech:

Seven ages: first puking and mewling;

Then very pissed off with one’s schooling;

Then f**ks: and then fights

Then judging chaps’ rights

Then sitting in slippers; then drooling.

Boy, it always ends the same way, doesn’t it. And then again, as Bernstein says in “Citizen Kane” about old age: “It’s the only disease, Mr. Thompson, that you don’t look forward to being cured of.”

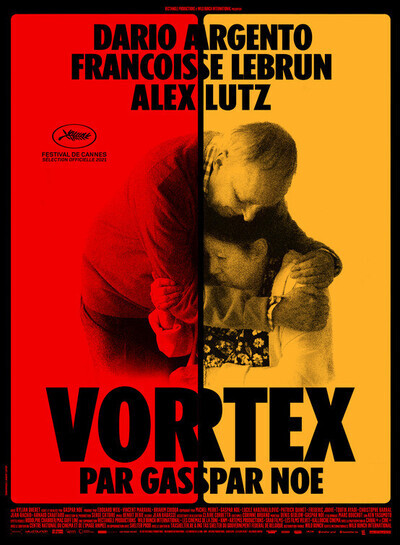

What better subject, then, for one-time cinematic enfant terrible Gaspar Noé to confront? In a sense, it’s no surprise that this hammeringly realistic chronicle is his most nightmarish film. As it happens, it’s also his most compassionate.

“Vortex” begins with what are usually a film’s end credits, but unlike “Irreversible,” his 2002 provocation, this movie does not unspool backwards; the tail end is presented first because this is a movie about endings. Its dedication is “To all those whose brains will decompose before their hearts.”

The unnamed couple in the movie are introduced by the years of their birth, which we will see matches the birth years of their embodiers—1940 for Dario Argento, 1944 for Françoise Lebrun. We first see them on the outdoor patio of their Paris apartment, drinking a genial toast. It’s the sole moment of serenity we’ll witness between Him and Her. Noe also presents a 1964 video of French singer Françoise Hardy singing the winsome tune “Mon Amie la Rose” and somehow here the chanteuse’s fresh-faced beauty is itself heartbreaking. And from here the movie doesn’t let up.

As with his recent short film “Lux Aeterna,” here Noé keeps in split-screen mode almost throughout. Right off the bat, he uses it to terrifying effect. As Argento’s character putters in his office and starts typing in the classic two-finger pecking method (his character is, as it happens, a film historian/critic, writing a book about cinema’s relation to dreams), Lebrun’s Her takes out the trash ... and wanders into the streets of her neighborhood, without aim. She goes into a dark sundries store and asks where the toys are. What toys? And for whom.

She is suffering from dementia, and soon He becomes fretful and goes out looking for her. He retrieves her. But soon we learn he’s not an ideal caretaker. Not because he’s also got a mistress with whom he allows himself to get preoccupied about at moments—despite his being of Italian background, he is a longtime French resident after all—but because his own health isn’t that great. He’s got heart issues, there’s a stroke in his history, and he coughs rather too robustly, beginning in the relatively idyllic patio scene.

Noé’s use of split-screen mostly serves to depict a kind of dual consciousness; one is on Her channel, the other on His. But the filmmaker changes it up every now and again, particularly when the couple’s son, Stéphane (Alex Lutz), visits their cluttered apartment with his young son Kiki. In these scenes the lenses are trained on two halves of the same moment. But the camera positions are not exactly synched up, or maybe each camera has a slightly different lens—the effect is that people sitting across a table looking at each other do not have matching eyelines. This is arguably an obvious visual metaphor, but it’s also an effective one. Because even without the challenges of old age, this is, like pretty much every other family, one that could use healing.

Stéphane has drug use and mental illness in his past, and an estranged wife. His own struggles add a dimension of suspense and dread to the story. For as much as we know how things are going to turn out for its central couple, Noé’s unflinching story telling keeps us hanging in concern and empathy.

One cannot necessarily be blamed for suspecting that the casting of famed horror director Argento in the male lead was some kind of stunt. But the proof that it wasn’t is in the performance. Argento is terrifyingly convincing in both his line readings and his physical acting; the role makes demands on his body that he fully meets. Lebrun, the female lead of Jean Eustache’s monumental counterculture drama “The Mother and the Whore” on the one hand, and a supporting player in Nora Ephron’s “Julie and Julia” on the other, is similarly harrowingly convincing as a character coming in and out of a fog of befuddlement, no longer able to connect to any emotion but regret.

Their apartment functions as a separate character, stuffed with artifacts and books and posters that tell you where they came from; these are children of the abortive revolution of the 1960s, still keeping a poster reading “Nix On War” hanging in one of their rooms. Their idealism is a casualty of their demons. And the movie’s most wrenching and convincing demonstration is that the worst demons we have to contend with are the ones we conjure for ourselves. Until disease starts getting clever with us, compounding the terror for which we are never fully prepared.

One leaves "Vortex" feeling cleansed by fire.

Now playing in theaters.

Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. He has written for a host of other publications and resides in Brooklyn. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here.

148 minutes

Dario Argento as Lui

Françoise Lebrun as Elle

Alex Lutz as Stéphane

Kylian Dheret as Kiki