“She became obsessed with the idea that our world wasn’t real, that she had to wake up to get back to reality.”

We’ve all felt a bit of displacement in 2020, the sense that the world around us isn’t real, that we’re in a dream from which we need to wake up. The timing of a newly-printed 70MM run of Christopher Nolan’s “Inception” at the Music Box Theatre in Chicago is due to the film’s tenth anniversary and as a prelude to the release of the acclaimed director’s “Tenet,” but the film carries a different energy in our dreamlike state of Summer 2020. Everything does, really. However, watching “Inception” a decade after its release, one is struck by how remarkably timeless the film feels. It could easily come out today and make just as much money, maybe even more, which is not something that can often be said ten years after the release of a blockbuster, especially one as effects heavy as this one. What is it about “Inception” that makes it feel so current?

First, a confession: I turned down a chance to see the new print. I couldn’t do it. While I’m not going to judge someone who is ready to run back into movie theaters as the pandemic continues to thrive, I’m just not there. After much discussion with family, it actually came down to a simple argument. While my logical brain knows the chance that anything could happen is statistically insignificant—Music Box is doing an amazing amount to alleviate risk, including configuring their ventilation so it doesn’t recycle air and only pushes in fresh from outside—my emotional brain would have been too distracted to concentrate, not only during the screening but for days after, when every cough and sniffle would incite panic. I feel like I’ll be ready soon (although only for Music Box's extreme precautions). I wasn’t yet.

And there’s a certain irony in not being physically or emotionally ready for “Inception” specifically. After all, it’s about a man, Leonardo DiCaprio’s Cobb, who is running from reality, digging deeper into levels beyond normal existence in an effort to flee his own grief, trauma, and blame. Nolan brilliantly spaces out revelations about Cobb’s purpose in his existential heist film. On one level, it’s a story about corporate intrigue, but that’s really a cover for the emotional arc of Cobb, who is dealing with his perceived failure to protect his wife, and belief that his action led to her suicide. Cobb is somehow both fleeing reality and trying to fix it at the same time. Who can’t relate to a sense of immobilized anxiety in 2020, in which we feel like we should be doing something but are stuck in our own forced routine? Or the idea that we have to push through something that feels like a bad dream to come out the other side?

Leaving aside my apprehension about seeing the film in theaters, a repeat viewing of “Inception” at home clarifies how many levels Nolan is working at the same time, much like the layered dream state of the narrative. On one level, it’s a whiz-bang action movie complete with set pieces that feel inspired by 007, especially in the final act. It’s an undeniably complex film narratively, even if that has been overblown—one that always feels like it’s a step ahead in terms of unpacking exactly what is happening—and yet it’s also a remarkably easy film to just let unfold, experiencing it beat by beat instead of trying to piece it altogether, much like, well, a dream. We don’t ask ourselves what dreams mean while we’re experiencing them—we simply ride them out. "Inception" works best when you're not trying to parse exactly what's happening and when, and you allow the emotion and action to carry the experience.

The reason it’s easy to get carried away by “Inception” is simple: it’s one of the most propulsive major blockbusters in history. It never stops. The stunning trick of “Inception” is how Nolan made such a talky film that never drags. It’s constantly explaining what it is and what it’s doing in a way that should grind it to a halt—over-exposition is the death of the action blockbuster—and yet Nolan balances that with such robust, passionate filmmaking. Whether it’s Wally Pfister’s rich cinematography, one of Hans Zimmer’s best scores, or Lee Smith's sharp-but-never-hyperactive editing, there’s confidence in every frame.

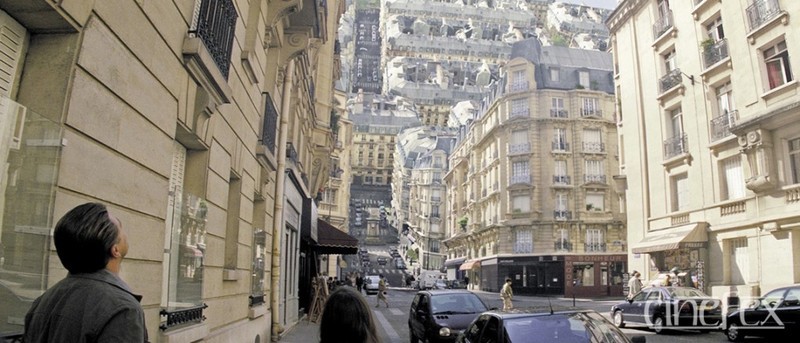

It’s also a film that, for better or worse, served as a tentpole for our puzzle box culture, one that loves to analyze and interpret art to extremes never imagined before the internet (go Google "Inception Ending Interpretations" and come back in about 12 hours). By the time he made “Inception,” Nolan had already fed this beast with films like “Memento” and “The Prestige,” but this takes it to another level by also serving as a commentary on puzzle box creation. “Inception” can very easily be read as a commentary on filmmaking. As Cobb and Ariadne (Ellen Page) work through the concept of dream construction, it echoes the way Nolan views his art, embedding each layer of the film with different ideas, maybe even working his own way into the viewer’s imagination. The dreamer, or viewer, can't know they're in a dream, much like the illusion of the film experience is best left unbroken.

As Roger said, “The film's hero tests a young architect by challenging her to create a maze, and Nolan tests us with his own dazzling maze. We have to trust him that he can lead us through, because much of the time we're lost and disoriented.” Nolan loves to play with perception, and so a film about how what one sees and feels may be a construction is arguably the most perfect fit of creator and creation in his career to date.

One thing that really struck me watching “Inception” in 2020 was how certain I am that the movie would land with the same impact as it did ten years ago. This is rarely the case. CGI starts to look dated, a celebrity falls from grace, ideas grow stale—none of that happened to “Inception.” Part of it is how much Nolan has stayed current as a filmmaker with follow-ups like “Interstellar” and “Dunkirk.” A blockbuster can often feel dated when it’s the last good thing that anyone involved made, but DiCaprio and Nolan are arguably more popular a decade later. It’s still breathtaking that a movie this complex made over $800 million worldwide and was nominated for Best Picture, but I am certain that both of those things would happen again if it was released in 2020. Well, maybe not in Summer 2020, but you get the idea.

So this is not a typical anniversary. Most of the time, these occasions feel like an opportunity for critical hindsight. They often come with words like “underrated” or, lately, “problematic.” What did people miss then? How does it play differently now? “Inception” defies this analysis, at least on its tenth anniversary. It’s still working its way through our imagination, something that feels even more important than it did when the film came out. Part of its brilliance is how much we’re all still kind of staring at that spinning top, waiting for it to fall.

For more information about the Music Box Theatre's special 70mm presentation of "Inception," click here

Brian Tallerico is the Editor of RogerEbert.com, and also covers television, film, Blu-ray, and video games. He is also a writer for Vulture, The Playlist, The New York Times, and Rolling Stone, and the President of the Chicago Film Critics Association.