Now streaming on:

In 1982, Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai traveled to the occupied territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip before and during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Gitai and a small crew shot a travel diary that examined a civilian view of war, contrasting Palestinian and Israeli experiences in the area. The resulting film “Field Diary” took a critical view of the invasion and the Israeli government’s treatment of Palestinian refugees. When “Field Diary” premiered in Jerusalem, it immediately created controversy and provoked hostile reactions from the populace and the military alike. Gitai left the country and emigrated to France where he lived until he returned to Israel in 1993, after Yitzak Rabin was elected prime minister and the first Oslo Accords were signed in Washington D.C.

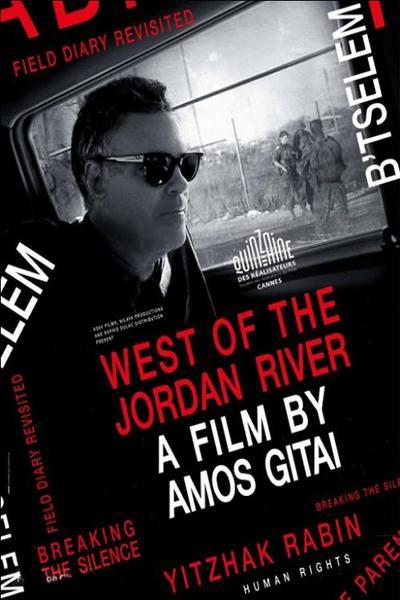

Now, 35 years later, with the occupation issue at a frustrating standstill, and a conservative, reactionary government in power, Gitai returns to the occupied territories for his follow-up film diary “West of the Jordan River.” Gitai explores the wizened discontent of Israeli and Palestinian civilians, and how some have tried to help mend the conflicts that the government has catalyzed. He interviews activists, journalists, current and former government officials, as well as unaffiliated citizens to craft a portrait of a region in static disarray.

For the most part, Gitai provides a platform for marginalized voices to speak freely, an approach that works best when he profiles organizations like The Parents’ Circle, which gathers Palestinian and Israeli parents who have lost children in the conflict to share their grief, or B’Tselem, a human rights group that aids Palestinian women to capture injustice on video. But “West of the Jordan River” works best when Gitai involves himself in the interviews. Gitai is a compelling screen presence—empathetic and patient, but also skeptical and necessarily forceful. He shines when he pushes back against his subjects, such as when he expresses disbelief at a journalist’s claim that human rights NGOs, like Breaking the Silence, are working in tandem with an international campaign to destroy Israel as a Jewish country. At one point, he tries to explain to a group of Palestinian refugees that anti-peace coalitions on both sides are much stronger than groups that seek reconciliation, but his words fall on indifferent ears.

Gitai’s methodology is certainly valid, and there’s value in a tribute to the courage of individuals trying to rectify problems created by a centuries-old conflict and exacerbated by ideologues. But beyond its social or political aims, “West of the Jordan River” fails to compel as a film. Aesthetically speaking, it’s at best functional, and at worst completely disinterested. It lumbers from interview to interview without much semblance of structure (beyond Gitai’s bookended interviews with Rabin from 1994), and Gitai’s subjects often parrot similar talking points, frequently rendering individual voices muddled. Gitai tries to communicate valuable information, but his method of delivery is severely lacking. I have not seen “Field Diary,” so it’s entirely possible I’m missing certain parallels or callbacks that would lend “West of the Jordan River” some extra weight. But it’s difficult to ignore the sections of this film that feel merely slapped together.

With “West of the Jordan River,” Gitai seeks to create a series of “human encounters,” and there are times when this intention shines through. The best scene in the film features Gitai conversing with a child who lives in Hebron. When asked about his dreams, the child cheerfully replies that he wishes to die a martyr. Gitai tries to communicate to him that life is worth living, but the kid, frustrated and befuddled by the line of questioning, casually says that he knows life is good, but dying for a cause is simply better. This is a complex, layered interaction that has its own identity, and communicates volumes about the state of the human condition in the occupied territories. It’s a shame that the rest of “West of the Jordan River” cannot live up to this brief vignette that seems to encapsulate exactly what Gitai tries to accomplish. Instead, we’re left with a film that has a lot to say but lacking the appropriate way to say it.

Vikram Murthi is a freelance writer and critic currently based out of Chicago, IL. He writes about film and television for RogerEbert.com, The A.V. Club, and Vulture. He previously was a chief film critic at Movie Mezzanine and a news writer for IndieWire. You can follow him on Twitter @fauxbeatpoet.

88 minutes