Now streaming on:

You won’t get much from written descriptions of Gaspar Noé’s nightmarish experimental horror short “Lux Aeterna.” The name just below “Lux Aeterna,” which depicts strange events during the production of a fictional witch-themed horror movie within the movie, matters more. Noé (“Vortex,” “Irreversible”), an aggressive and generally effective provocateur, has earned a name not only thanks to his ostentatious formal experimentation—in “Lux Aeterna,” he uses split screens to show action in two different places at once—but also his manic combination of playful nihilism and grim psychedelia. There’s very little chance you’re going to wander into his latest without some expectations.

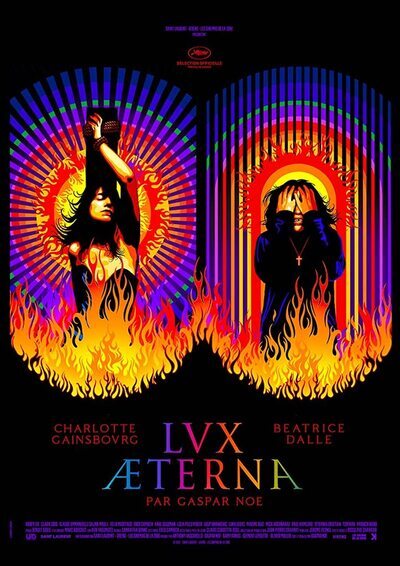

Still, let’s assume you don’t know what to think when you read that “Lux Aeterna” is really “Lux Æterna—A Film By Gaspar Noé.” That’s how the movie’s being advertised here, a reflection of Noé’s simultaneously whimsical and self-serious kind of gallows humor. This is a movie in which a trio of actresses—Beatrice Dalle, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and Abbey Lee—are driven out of their minds and then posed as witches burnt at the stake during a making of “God’s Work,” a movie within the movie.For some reason, only two of those women get to star in a dialogue presented through a split-screen diptych. It’s the movie’s best—and largely improvised—introductory scene, and it only features the two French co-leads (Lee’s good, but her part’s not much).

All three women in “Lux Aeterna” have anxieties that slowly escalate instead of traits that meaningfully develop. That’s allowed, especially in a 50-minute short movie that’s more about ambience than plot. Still, it’s hard not to eventually see the sketchy nature of these protagonists as a revealing afterthought, especially knowing that Noé shot this movie in five days’ time in order for it to be considered for the 2019 Cannes Film Festival (where it ultimately premiered).

In a series of quotes, “Lux Aeterna” professes to be about filmmaking and the demonization of women as mutual parts of art as icon-making process. The movie’s consideration for filmmaking as a gendered art predicated on women-unfriendly “sexocide” (Noé’s phrase, in the movie’s press notes) can be gleaned from clips of earlier movies, particularly “Day of Wrath” and “Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages.” There are also some inter-titles about the role of the filmmaker, all from impassioned directors like Luis Buñuel, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Buñuel gets the final word of the movie after the end credits: “Thank God I’m an atheist.”

There are also some choice details in Dalle and Gainsbourg’s establishing conversation, in which they, playing versions of themselves, talk about their respective movie-acting careers. Dalle mirthlessly jokes about the variable quality of her work and then proceeds to threaten and push back against the male filmmakers of "God’s Work," who are either paranoid or apathetic or both.

Countless distractions and irritants beset Dalle, Gainsbourg, and Lee: A pushy boyfriend, a paranoiac producer, a domestic situation involving a tattoo over a young girl’s “foo-foo.” Of the three women, Gainsbourg’s mood gets the most development and consideration. She passively listens to Dalle during the above-mentioned improvised conversation, and then struggles to understand a litany of demanding hangers-on who swarm her as soon as she and Dalle separate. Gainsbourg also serves as the centerpiece of the movie’s assaultive conclusion: a battery of strobing primary colors. Noe’s split screens also tend to be an effectively alienating showcase for his heroines’ conjoined, but separate afflictions.

The finale of “Lux Aeterna” tells you some things about the movie and its commanding wispiness. Noé doesn’t really seem that interested in complicating his loaded and barely sensible vision of filmmaking as a medium designed to subjugate and drain its (female) stars of their character-defining vitality. Instead, all the little things that drive Noé’s women out of their minds only end up seeming like relatively benign symptoms of an unholy energy that eventually possesses everybody on the set of “God’s Work.” The machine starts operating itself, despite individual collaborators’ obstructing micromanagement and interruptions. And by the time that Gainsbourg appears on set: the sight of an inflamed woman writhing on a wooden stake looks less like a tragic ritual than a blackly comic surrender to dark forces from well outside this movie’s reality.

Then again, this movie’s reality mostly exists because of the line that comes after its title. Noé is a master of dreadful ambience and in “Lux Aeterna,” his collaborators do another great job of overwhelming viewers with his commanding, even dictatorial style of image-making. The movie’s half-hearted jokes, on frustrated women artists and their blind male collaborators, tend to be one-note and thankfully besides the point. But if you adjust your expectations, you’re more likely to accept “Lux Aeterna” as a vigorously realized doodle.

Now playing in select theaters.

Simon Abrams is a native New Yorker and freelance film critic whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

51 minutes

Charlotte Gainsbourg as Charlotte

Béatrice Dalle as Béatrice

Abbey Lee as Abbey

Karl Glusman as Karl

Clara 3000 as Clara 3000

Claude Gajan Maude as Claude-Emmanuelle

Félix Maritaud as Félix

Mica Argañaraz as Mica