Now streaming on:

David Cronenberg is near the top of the list of directors whose works resist snap judgments. His mix of black comedy and unabashed melodrama is so delicate, and in some ways so off-putting, that at times it's hard to tell if he's kidding or serious (the answer is usually both). He's been described as a horror filmmaker, and his longstanding fascination with bodily invasion and the fragility of flesh confirms that label—or does it? A good many of his films play like horror movies even if they don't have genetic mutations or other obvious "monsters." Why? Maybe because he's less interested in gore and goo than in the beasts within: the monstrous nature of obsession and desire; the difficulty of escaping oneself, physically or emotionally; the cruelty of the societies that enfold and define his characters. Look back over Cronenberg's filmography, and you realize that he hasn't made an according-to-Hoyle horror picture since 1986's "The Fly." The horrific quality seems to come more from his being appalled by what people can be, and do—and from being sympathetic to their urges anyway.

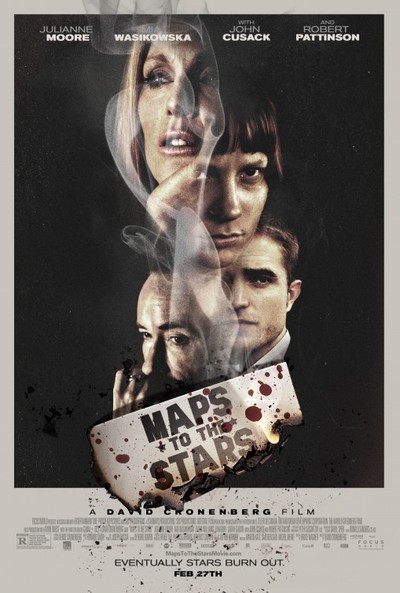

"Maps to the Stars," written by Bruce Wagner, is another work in the good old Cronenbergian vein. Although it's been dismissed in some quarters as minor Cronenberg—and criticized for "getting Hollywood wrong," or something like that; as if "Dead Ringers" cared about the fine points of gynecology—it's a sneakily powerful movie, so much so that its conceptual thinness isn't a deal-breaker. Not for nothing did Cronenberg model his remake of "The Fly" on tragic opera, then re-stage it with his regular composer Howard Shore as an actual opera, with a libretto by David Henry Hwang. This new film's cast of anxious, duplicitous, sometimes violent creative types rattle off declamatory dialogue so overwrought that it could be treated as arias scored for a 40-piece orchestra. The characters inhabit a Los Angeles that seems as intimate, even inbred, as a stereotypical backwoods town: every other scene reveals that characters you didn't know were connected are, in fact, part of an extended family, united not just by blood, but hunger for validation. They want luxury and fame as well, but those are signifiers of what they're truly after: adoration. Love. Unconditional acceptance.

Julianne Moore stars as Havana Segrand, a formidable actress whose star has begun to fade now that she's passed 50. Like a lot of characters in this film—and a lot of characters in Cronenberg's films, period, and Wagner's fiction—she's defined by her tragic past, and knows this all too well, and is palpably desperate to escape it and re-create herself. Ironically, though (and appropriately, since this is Cronenberg) she's trying to escape herself by crawling deeper into a psychological cage that's enclosed her since birth: Havana wants to star in a biographical drama about her late mother Clarice Taggart (Sarah Gadon), a mercurial, psychologically and sexually abusive actress who could be a combination of Frances Farmer and Joan Crawford.

This one subplot, about an actress trying to master the awful memories of her mother by figuratively becoming her, gives you some clue what Cronenberg and Wagner are up to, not just with Havana but with all the major characters. Like Cronenberg's little-seen but fascinating "Spider," "Maps to the Stars" often feels like a ghost story made by people who don't believe in the supernatural. The mother appears to her daughter in a very straightforward way—as she might manifest herself in a theatrical production. But even though she's clearly an outgrowth of Havana's mangled psyche, you have to count her as an accusing spirit, rattling around in the haunted house of her daughter's damaged mind, and saying the most vile, undermining things. (As if the movie didn't already subtly echo "The Shining," Cronenberg has Clarice appearing to Havana in a bathtub: shades of room 237.)

Havana, who will do or say just about anything to play her mother and hopefully win an Oscar, is the most vivid of the film's troubled souls, thanks mainly to Moore's utter disinterest in seeming powerful or dignified or otherwise stereotypically movie star-like. From "Short Cuts" and "Safe" onward, this actress has played troubled, desperate or generally put-upon characters so often that the best actress Oscar she won for "Still Alice" might as well have been mounted on a torture rack. But Havana proves merely the brightest star in this film's constellation of scheming sufferers, a bunch whose manias are a bit too contrived and schematic, but which fascinate anyway, thanks to the actors' virtuosity and Cronenberg's control of tone.

Havana's regular therapist/masseuse/TV psychologist is a self-help guru named Dr. Stafford Weiss (John Cusack), a man who presents himself as selfless and caring, but seems determined to crack open repressed minds mainly so he can root around and provoke extreme reactions. (When Stafford manipulates Havana's body on a yoga mat, Cronenberg's staging suggests sex, sometimes rape.)

Havana's new personal assistant, Stafford's daughter Agatha Weiss (Mia Wasikowska), wears long gloves to cover arms that were burned in a mysterious fire; at first she seems almost Pollyanna-sweet, but soon enough she reveals a capacity for ruthlessness that rivals Havana's. The ghost story parallels continue via Agatha, who haunts Stafford; his brittle, fearful wife Cristina (Olivia Williams, in the latest in a series of knockout supporting performances), and Agatha's kid brother Benjie. The youngest Weiss is a cruel and territorial former child star who's looking to escape the gilded prison of juvenile idol-hood. Benjie is played by Evan Bird of "The Killing," an actor whose haircut and clipped delivery revoke Frankie Muniz on "Malcolm in the Middle" when the character isn't doing a snotnosed power-broker routine, lounging around nightclubs like Leonard DiCaprio in his post-"Titanic" period. Compared to all these misfits, slimeballs and emotional basket cases, Robert Pattinson's limo driver and aspiring screenwriter Jerome Fontana seems well-adjusted, but as is so often the case with Wagner's characters, you'd best not get too comfortable with him. (This is the second time Pattinson has spent time in a limo for Cronenberg, after "Cosmopolis," and the second time he's delivered a top-notch, blase-sexy-decadent performance.)

I'm not convinced that the film's themes and situations are deep enough or well-articulated enough to deserve the brilliant filmmaking and acting placed in their service. As the story wears on and we glean new bits of information establishing the characters' connections, the story starts to seem less operatically inevitable than contrived and convenient: too neat, and trying to camouflage its too-neatness with wrenching scenes of violence and self-abasement. By the time you get to the end, Cronenberg has pinned all his people against the screen like so many laboratory specimens, ripped off their scabs, and vivisected their longings: an old wound here, a long--deferred dream there. Still, the movie sticks with you. It's a fleeting nightmare that refuses to fade.

Matt Zoller Seitz is the Editor at Large of RogerEbert.com, TV critic for New York Magazine and Vulture.com, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in criticism.

111 minutes

Julianne Moore as Havana Segrand

Mia Wasikowska as Agatha Weiss

Evan Bird as Benjie Weiss

John Cusack as Dr. Stafford Weiss

Robert Pattinson as Jerome Fontana

Sarah Gadon as Clarice Taggart

Olivia Williams as Christina Weiss